This time, the banks were ready: How the Big Four prepared to survive the coronavirus

This article is part of a Fortune Special Report: Business in the Coronavirus Economy—a look at the impact of the pandemic on more than 50 industries.

For the past decade, the big U.S. banks have endured arduous annual Federal Reserve “stress tests” gauging their strength to weather another Great Recession–like crisis. Critics groused that forcing financial titans to build gigantic war chests—modeled to withstand a replay of double-digit joblessness and an eight-point drop in GDP—was unnecessarily cautious. But, lo and behold, banks are suddenly confronted with a scenario even worse than the regulators’ worst case. “The banks were kicking and screaming while the government made them build capital and liquidity,” says Mike Mayo, an analyst with Wells Fargo. “But that’s why they’re in such good shape today.”

Indeed, the stress-test policy appears absolutely crucial now, given the damage that the coronavirus pandemic is unleashing on Wall Street. From the start of 2020 through early April, the KBW banking index dropped 33.6%—20 points more than the S&P 500. JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon warned in his annual letter that the bank’s earnings would “be down meaningfully” this year, conceivably endangering its dividend. And both boutique firm Wolfe Research and investment bank KBW forecast that profits for the Big Four banks—JPMorgan, Bank of America, Citigroup, and Wells Fargo—could crater more than 60% if a recession extends into 2021.

The crisis has pushed the major commercial and investment banks into a new cycle of much lower earnings. But in a reversal from 2008, their profits should remain positive even in the direst scenario. Plus, they’re entering a sharp downturn flush with capital and liquidity. Whereas Wall Street was the problem in the Great Recession, today the lenders and underwriters have the resiliency to be part of the solution—as conduits for channeling as much as $4 trillion in emergency funding to businesses large and small, and continuing to extend credit to their regular customers, from automakers to hairdressing salons.

Partly dictated by the Fed, the big banks entered 2020 boasting their strongest capital levels since 1940.

The banks built up their finances in what has been a near-golden period for the industry over the past 10 years. They benefited from a combination of a strong economy and conservative management—partly dictated by the Fed, and partly imposed by such leaders as Dimon and BofA CEO Brian Moynihan. Banks diversified into areas that generated steady earnings, notably by building and buying wealth management franchises. Most of all, pushed by the stress tests, the banks shored up their capital. From late 2008 to 2019, equity capital as a share of the balance sheet rose 51% at JPMorgan, more than doubled at BofA and Wells, and tripled at Citi. Entering 2020, the big banks boasted their strongest capital levels since 1940.

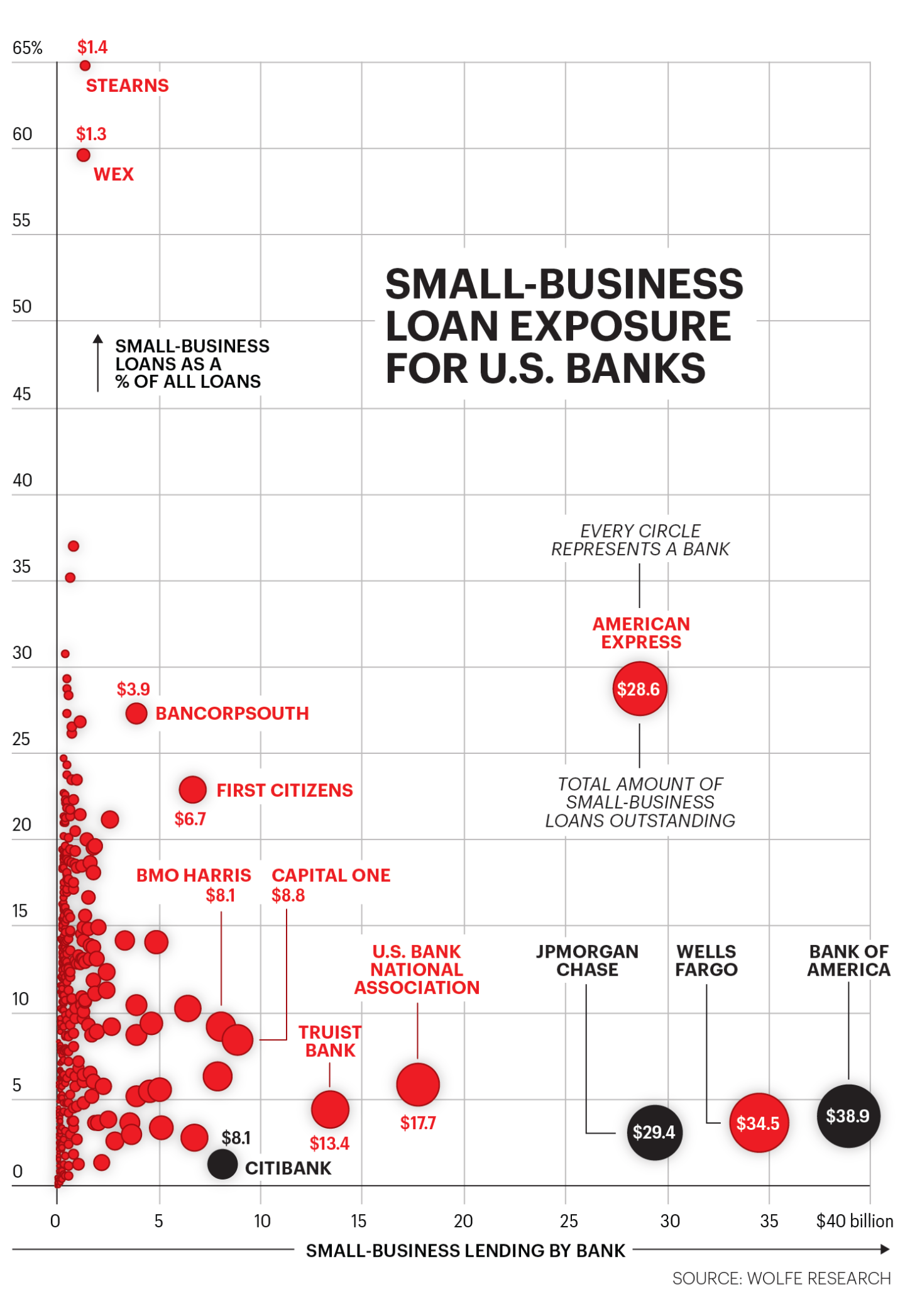

That staying power is crucial to seeding a recovery. The major banks are a giant source of funding to small- and medium-size businesses, or SMEs—typically enterprises that employ up to 10,000 and issue paychecks for over 70% of U.S. workers. At year-end 2019, the Big Four held $836 billion in “commercial and industrial” or C&I loans to SMEs. That was 45% of the total for all U.S. banks. The Big Four also provide the likes of hotel owners and developers $422 billion in financing, equal to 28% of all commercial real estate lending provided by America’s banks.

The economy’s shutdown is starving SMEs for cash. The stimulus plan marshals the banks to originate and service government-guaranteed loans to as many as 17 million of these enterprises. The aid designed to flow through the lenders comes via two main vehicles. The first is the $349 billion Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). It makes loans of up to $10 million mostly to companies with 500 or fewer employees. And if a company’s payroll stays the same for eight weeks after it gets a loan, the debt is forgiven. The PPP is a good thing for America’s banks, including the Big Four. The lenders take no credit risk, and, according to interviews with bankers, the fees paid to originate the loans make them profitable, especially for amounts up to $2 million.

Since most of the loans are likely to become grants, the PPP will help bridge their clients through to the recovery without adding to their debt load. Plus, fragile businesses can use the new loans, charging 1% interest, to pay the interest on existing, at-risk borrowings at, say, 4% or 5%—lifting their cash flow. Put simply, the PPP lowers the banks’ credit risk by providing either grants or cheaper, guaranteed financing to small businesses, and lowering the number of bad loans going forward.

The second program is less of a slam dunk for banks. The Main Street Lending Program will extend loans to medium-size businesses employing up to 10,000 people. For the Big Four, that category is several times the size of their small-business books. The Fed is providing the cash and the Treasury is guaranteeing 95% of the financings; the banks will keep just 5% on their books. Under the Fed’s plan, up to $600 billion in Main Street loans will be offered. But these loans are a different species from the relief offered by the PPP. The borrowers have to repay the government. If they default, the U.S. can protect taxpayers by seizing assets or forcing them into bankruptcy.

For the banks, the Main Street program could pay off by supporting their clients through a few more difficult months. But if a recession stretches into late this year or beyond, many struggling, overleveraged companies might need to seek additional emergency funding. That would create a quandary for the banks, who will certainly face intense pressure from regulators to make the loans. In that scenario, the banks will need to draw on every bit of the financial strength they built up over the past decade.

A version of this article appears in the May 2020 issue of Fortune with the headline “This time, the banks were ready for a crisis.”

More coronavirus coverage from Fortune:

—22 million lost their jobs in the past month—real unemployment rate likely near 18%

—How Fortune 500 companies are utilizing their resources and expertise during the pandemic

—Inside the surreal “Mask Economy”: Price-gouging, bidding wars, and armed guards

—The IRS just launched “Get My Payment” portal for tracking your stimulus check status

—How every sector of the S&P 500 has been impacted by the coronavirus selloff

—If you’ve been a little busy lately, here’s what’s going on with the 2020 election

—Military experts: We need to fight coronavirus like we fight insurgents on the battlefield

—PODCAST: COVID-19 might have upended the concept of the best companies of the year

—VIDEO: 401(k) withdrawal penalties waived for anyone hurt by COVID-19

Subscribe to Outbreak, a daily newsletter roundup of stories on the coronavirus pandemic and its impact on global business. It’s free to get it in your inbox.