Big Pharma has the chance to come to the world’s rescue

This article is part of a Fortune Special Report: Business in the Coronavirus Economy—a look at the impact of the pandemic on more than 50 industries.

In August 2019, barely half a year before the world changed, the pharmaceutical industry was the most disliked business sector in America: 58% of those polled by Gallup had a negative perception of the industry, more than twice the share who viewed it favorably—giving drugmakers a net positive score of minus 31, the worst by far of any business sector in the country. For comparison, airlines and the legal profession had net positive scores of plus 19 and plus 5, respectively. Even the federal government (minus 27) had better ratings overall.

Enter the coronavirus. As much as the pandemic has devastated many industries, it has offered Big Pharma a chance to shine as never before, winning back the trust of a public infuriated with years of soaring drug prices. Will they seize the moment? The answer depends in large part on how fast drug and device makers make progress in three areas essential to beating back COVID-19. The first is in the realm of diagnostic tests that can identify not only who has the disease but also who’s no longer infectious and therefore safe to return to work. Second are therapies to shorten the disease course and lessen its severity—which will be important for reducing the burden on hospital ICUs and exhausted critical care teams. And third are vaccines: Without a safe and widely disseminated vaccine to confer immunity on a huge swath of the population, it’s hard to imagine life returning to something resembling “normal.”

Success in these three areas won’t put the pricing controversies to bed. As they strive for novel therapies and medical tools, pharma companies will have to balance the need to fund innovative projects and still satisfy a public (and perhaps regulators) demanding low- or no-cost drugs and devices to combat this plague. Still to be determined is what role health insurers and governments may play in all of this.

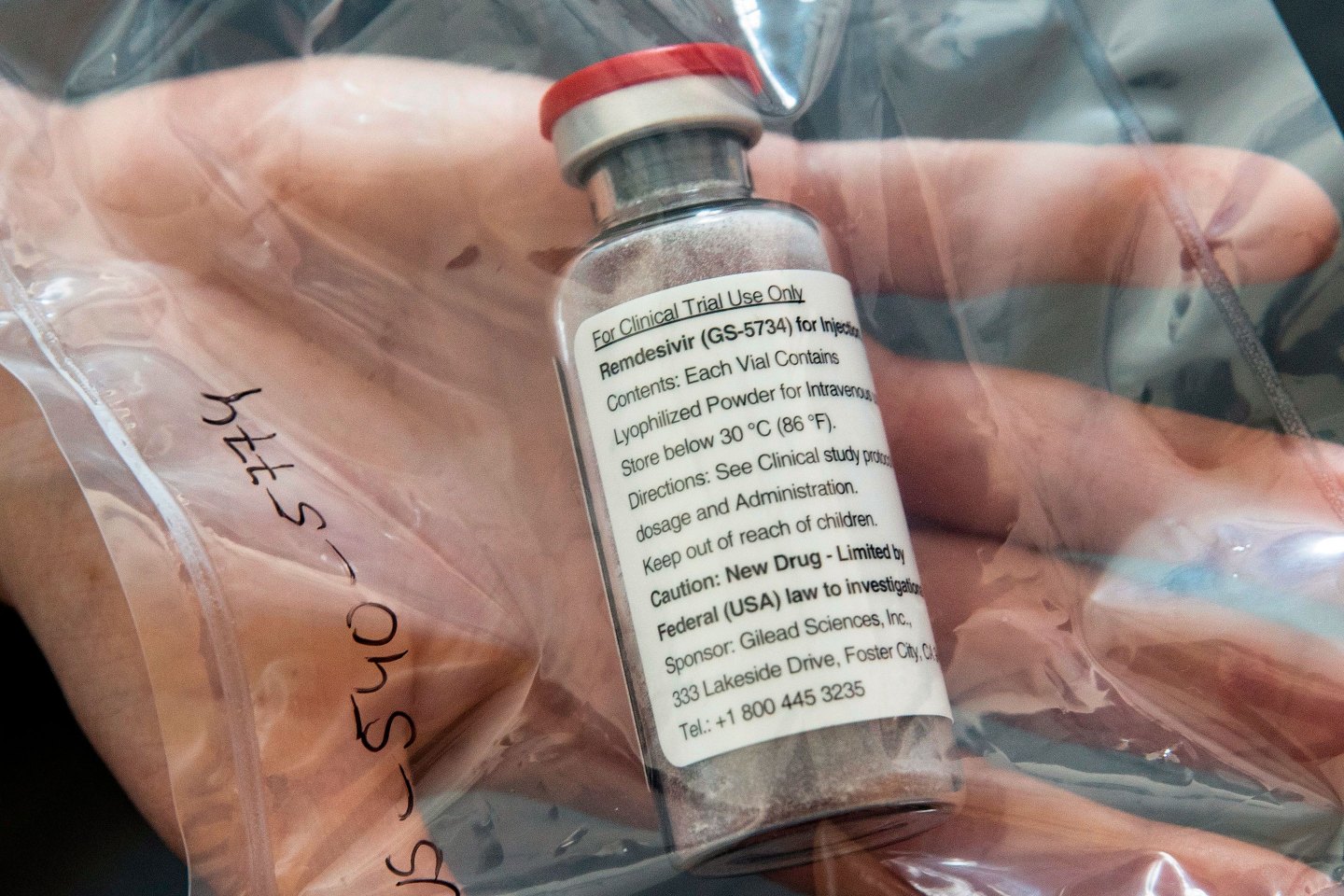

Gilead Sciences, which likely has the most advanced anti-COVID-19 drug of the bunch, has consistently stated it doesn’t expect to make much money off of its antiviral product, remdesivir. SVB Leerink’s lead pharma analyst Geoff Porges tells Fortune the company will be under tremendous pressure to put a reasonable price tag on the drug. Indeed, the blanket uncertainty across the industry—on everything from pricing to the resiliency of supply chains to the difficulty of conducting clinical trials in an era of social distancing and overwhelmed hospitals—has prompted several firms, including Pfizer and AstraZeneca, to issue statements saying they can no longer offer financial guidance for the year.

Throw in the already fragmented nature of U.S. health care, a desperate public, a fast-changing timeline of government priorities, and anxious shareholders, and the result is something akin to an Olympic sprint in which dozens of runners are each competing on their own tracks. Predicting who’s got the lead in such a race isn’t easy. But Fortune reached out to dozens of companies, analysts, public health organizations, academics, and other experts to assess the state of progress.

One bit of good news: So far, even longtime cynics are giving the industry a qualified thumbs-up. Whether that’s enough to grant drugmakers a better grade than lawyers is another question.

Diagnostics

Fundamental to controlling the spread of COVID-19 are tests that can identify those who have been exposed to the coronavirus, which is easily transmitted by infected individuals—even, the evidence suggests, when they have no symptoms of illness. The standard test requires a quick swab of the throat or nose (or both), which grabs a tiny sample of mucus and analyzes it through a process called polymerase chain reaction. PCR amplifies the genetic material of the virus, if any is present, making it easier to identify.

PCR tests can quickly reveal who is currently infected with the virus, even if they’re asymptomatic. But they don’t show who may have previously been infected, silently or otherwise, and no longer carries the virus—thanks to the response of their body’s own immune system. In such cases, those formerly infected will have telltale antibodies in their blood. The antibodies circulate in the blood for a long while, keeping a careful vigil out for the virus should it reappear and standing ready to mount a counterattack if it does. That, in short, is an immune response.

Having an immune response (that is to say, antibodies) to a virus doesn’t necessarily mean a person has full immunity to it on subsequent exposure. But when it comes to returning people to work, it’s important to know who’s got at least some immunity and who doesn’t. Serology tests, which look for specific antibodies in a small sample of blood, can reveal that.

In recent weeks—and notably, after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention botched its initial PCR test—a spate of private and public health labs have rushed into the breach, creating a range of diagnostics for COVID-19. As of April 10, there were 33 FDA-authorized coronavirus tests—though the question of which ones work best may not be known for months, when there’s enough data out there to compare them, says virologist Pedro Piedra of Houston’s Baylor College of Medicine.

Swiss drug giant Roche developed the first commercial coronavirus diagnostic to receive emergency authorization on March 12—with Thermo Fisher Scientific, LabCorp, Quest Diagnostics, Abbott, Cepheid, Cellex, Becton Dickinson (BD), Henry Schein, and others—following quickly on its heels.

One standout is Abbott’s latest PCR test, ID NOW, which can deliver positive or negative results within minutes rather than hours or days, which had been the standard turnaround time. That’s because it can be conducted on far more portable machinery and uses something called “isothermal” technology, explains John Frels, VP of R&D at Abbott. Typically, molecular virus tests need to cycle through multiple temperatures in order to amplify a virus’s genetic sequence in patient samples; the Abbott test can do that amplification process at a more consistent temperature, speeding up the process. The test is slated to be used in drive-thru testing facilities set up by CVS Health in several states, which may place it in front-runner status.

On the serology front, both medical distributor Henry Schein and Cellex, a smaller biotech firm, have received authorization for blood tests that screen for antibodies to the novel coronavirus. While U.S. regulators have said there are scores of companies that have signed up to create antibody tests, one major problem is the spectre of profiteers hawking fake tests, something FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn has said the agency will crack down on.

Treatments

At press time, more than 75 coronavirus drugs are currently in development, according to research from Agency IQ. An additional 40 medicines, already approved for other indications, are now being tested as well against COVID-19.

“I think the best bet is still Gilead’s remdesivir,” says Porges, the SVB Leerink analyst, who is eagerly awaiting data from clinical trials that began in late February in China and which are expected to be published soon. Multiple other public health experts agreed.

Remdesivir, an investigational antiviral treatment, has been in development for years to treat various infectious diseases, including SARS and MERS-CoV, two illnesses caused by strains of coronavirus related to the COVID-19 pathogen. In a study of 53 seriously ill COVID-19 patients treated with the experimental drug through a “compassionate use” program, its results published in the New England Journal of Medicine in April, 38 patients (68%) showed measurable improvement. (In 15% of cases, the patients’ illnesses progressed.) Though the study, experts caution, was neither randomized nor controlled, two standard practices that help ensure results aren’t inadvertently skewed, the initial findings were promising—with response rates significantly higher, and mortality lower, than would be expected based on current data from hospitals today.

Antiviral medicines, which typically interfere with a virus’s ability to replicate, are rarely cures in the way that antibiotics (which kill bacteria) often are. But having a drug that can help patients breathe well enough to stay off a ventilator could be of enormous value in this pandemic. A single day on a hospital ventilator can cost $25,000, says Porges.

Gilead CEO Daniel O’Day released an open letter saying it would expand the number of available doses to 1.5 million, enough for 140,000 courses of treatment. A possible timeline could include emergency authorization within a few months.

Multiple other companies—including Takeda, Regeneron, and scores of other firms—are working on treatments. Those encompass antivirals, antibodies, or therapies derived from the blood plasma of patients who have recovered from COVID-19.

“There’s an incredible sense of urgency,” says George Scangos, CEO of Vir Biotechnology, a company working on both COVID-19 treatments and vaccines, including through a major collaboration with British drug giant GlaxoSmithKline. “The number of companies that want to contribute regardless of whether you make a lot of money is incredible.” Hal Barron, the R&D chief at GSK, concurs. “I meet weekly with most of the Big Pharma company heads,” he tells Fortune. “I’ve never seen a magnitude of urgency like this.”

Vaccines

Testing and treatments can only get you so far. With a virus as transmissible as the novel coronavirus, a vaccine is critical to establishing long-term public health safety. Making sure they work—and are safe—can take years, says Peter Hotez, dean for the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine. That said, time does seem to be speeding up. By mid-April, there were no fewer than 70 coronavirus vaccines in development, according to the World Health Organization; with those from China’s CanSino Biologics, Inovio, and Moderna already in human trials.

Moderna’s candidate tweaks the virus’s messenger RNA to elicit an immune response in humans. In earlier clinical stages, GlaxoSmithKline has partnered with multiple firms, including Vir and French drug giant Sanofi, that want to leverage its “adjuvant” technology—which can make it easier to produce more doses of a vaccine on a wide scale. Then there’s Pfizer’s collaboration with BioNTech in China; a partnership between Heat Biologics and the University of Miami; the Baylor School of Medicine with its investigational SARS vaccine; Novavax; and Johnson & Johnson.

70

Number of coronavirus vaccines now in development, according to the world health organization

But Johnson & Johnson seems to have produced the most buzz. In late March, J&J said its experimental vaccine might be in clinical trials by the fall of 2020 and on the market by early 2021. “Based upon our early data, we feel confident that we have got a very good candidate,” J&J CEO Alex Gorsky tells Fortune, adding this was a result of an investment in vaccine development technology made a decade ago, which “turned out to have much broader application than we anticipated.”

“This is a complicated virus that seems pretty good at avoiding the immune system,” says Vir chief Scangos. “It could be possible that COVID-19 vaccines are modeled after flu vaccines, which are somewhat effective, but would require wide-scale annual production” as new strains of the coronavirus emerge. “If we’re realistic, there’s risk.”

A version of this article appears in the May 2020 issue of Fortune with the headline “Will medicine makers come to the rescue?“

More coronavirus coverage from Fortune:

—How Fortune 500 companies are utilizing their resources and expertise during the pandemic

—Inside the surreal “Mask Economy”: Price-gouging, bidding wars, and armed guards

—The IRS just launched “Get My Payment” portal for tracking your stimulus check status

—Should you fear government surveillance in the coronavirus era?

—If you’ve been a little busy lately, here’s what’s going on with the 2020 election

—The coronavirus crisis is fintech’s biggest test yet—and greatest opportunity to go mainstream

—There are 32 authorized coronavirus tests so far—here’s how they differ

—PODCAST: COVID-19 might have upended the concept of the best companies of the year

—VIDEO: 401(k) withdrawal penalties waived for anyone hurt by COVID-19

Subscribe to Outbreak, a daily newsletter roundup of stories on the coronavirus pandemic and its impact on global business. It’s free to get it in your inbox.