VW is making an $180 billion bet to dominate EVs and catch Tesla

On a gray January morning in Wolfsburg in central Germany, the sky casts an icy stillness over Volkswagen’s mammoth headquarters. But inside the auto plant, it’s all color and noise, as blue-shirted workers lift molded steel doors off conveyor belts and wire up car interiors—building some of the hundreds of thousands of vehicles that roll out this factory’s doors like clockwork, year after year. Other than the many orange robots across the floor, the factory—the biggest manufacturing facility in Europe—has operated much the same way for nearly 84 years, ever since the auto giant was founded in 1938. So iconic is the Volkswagen complex that the German government has designated the buildings’ red bricks a protected landmark. “We cannot touch them,” a factory manager tells us as we walk past the walls.

If Volkswagen can follow through on its transformative blueprint, the bricks might soon be one of the few things left unchanged. The company envisions a path in which Wolfsburg gradually becomes a self-contained electric-vehicle factory, the hub of a global EV empire. Instead of fitting gas tanks and engines to car frames, workers will be slotting in battery cells. Millions of the company’s vehicles will be all-electric by 2030, and by mid-century, few fossil-fuel cars, if any, will be made here. “The world is changing very, very fast,” says CEO Herbert Diess, sitting in his executive offices overlooking the plant. Eighty-plus years’ success in auto manufacturing and design, he says, “is not sufficient for the future.”

It will take immense resources and know-how to succeed in this pivot. Though Volkswagen brought in an estimated €246 billion ($280 billion) in revenue last year, its time-tested business model is on its way out. Like the rest of the $2.3 trillion auto industry, it’s scrambling to transition away from the internal combustion engine and toward battery-powered EVs, in a market shift—driven by consumer demand, political imperatives, and a climate emergency—whose speed has caught legacy carmakers by surprise.

Producing at enormous scale is a point of pride for the Volkswagen Group, which delivers to its dealers more than 9 million cars in an average year. Its 12 brands include less-expensive vehicles like SEAT, Skoda, and Volkswagen itself, and luxury brands like Porsche and Bentley. In most years, it vies neck and neck with Japan’s Toyota to be the world’s biggest carmaker. But in an EV future, its dominance is far from certain. It faces not just old rivals in Japan and Detroit but nimble upstarts from California to China, the biggest of which—Tesla—sprinted from startup to industry leader in under two decades. And changing the company’s focus from internal combustion to EVs isn’t simply a matter of tweaking what works: It requires all-new production workflows, new supply chains, new skills and training, and what’s likely to be a much smaller workforce.

Closing the gap with Tesla anytime soon is wishful thinking. Volkswagen is a supertanker that has difficulties getting things done quickly.

Patrick Hummel, UBS

The financial stakes are high. Volkswagen estimates global auto-industry revenues will reach $5.7 trillion by 2030—most of it from EV sales, but a substantial amount from intellectual property like software services and technology platforms. By then, Volkswagen intends for half the vehicles it makes globally to be EVs—about 5 million a year, far more than the 453,000 it delivered in 2021.

If Volkswagen emerges as a victor in this EV war, profitability could be assured for generations. If it falls behind, or fails to create industry-leading software, it could steadily decline. The EV revolution will not come cheap: In December, the company committed a hefty €159 billion ($180 billion) over the next four years to transform its production, with the aim that by 2026, one-quarter of new vehicles would be battery-powered. For now, Volkswagen’s enormous scale and cash flow is making the shift attainable. But the question remains: Can a behemoth like Volkswagen evolve quickly enough to retain its dominance? Or will reinventing itself, from a bender of steel to a tech giant, prove too high a bar to clear?

Diess is leading this campaign in the wake of a bruising 2021. In December, he narrowly avoided being booted from his position by the board, after Volkswagen delivered its smallest sales figures in a decade—owing largely to a global shortage of critical semiconductors.

Having survived in his job, and just back from vacationing on the Canary Islands and the ski slopes of Austria, the 63-year-old Diess says he has learned hard lessons from the rocketing rise of Tesla. That company last year delivered more than 936,000 EVs globally, more than double Volkswagen’s total (though in Europe, Volkswagen was by far the EV leader). Perhaps the biggest risk going forward, Diess says, is his company’s innate cockiness, born from decades of success in making fossil-fuel cars. “In any transition, there is a danger that you underestimate your challengers,” he notes. “That is even more so if you are from a tradition that this is an empire, which is rock-solid and unbeatable.”

In 2018, shortly after he became CEO, Diess met with me in Wolfsburg to lay out for Fortune a far-reaching electric strategy, the first such plan announced by a major automaker. The plan had a dual purpose: to make the company a viable EV competitor, and to dig out from under its catastrophic diesel scandal, in which it was caught manipulating pollution monitors in millions of vehicles. (Volkswagen has so far paid about $32 billion in related fines.)

Today, Diess admits he was “struggling” during our earlier visit, facing skepticism about his EV plan within Volkswagen’s workforce. The company employs 670,000 people worldwide—and EVs, which have far fewer moving parts, require fewer people to build them. “Even two years ago, many people thought it is good to have no EVs here in Wolfsburg,” Diess says. “Now the contrary happens. People are really asking for fast change.”

Diess credits one person for the change in attitude: Elon Musk. The crucial moment came in December 2019, when Tesla’s CEO flew into Berlin and announced he was building his first European gigafactory in nearby Grünheide, a small town just a 90-minute train ride from the “rock-solid empire” of Wolfsburg. In an interview last year, Musk told me that the Grünheide factory would be capable of producing 500,000 cars a year—nearly the output of Wolfsburg—and would include a battery factory that would be “the biggest by far in Europe, and one of the biggest in the world.” Tellingly, he also said he and Diess had had “a number of conversations” and that he believed the Volkswagen CEO “really means it about taking electric vehicles seriously.”

Catching Musk will not be simple. Tesla has scaled up at a rate auto giants can only envy, and now has more than 20% of the global EV market. “Closing the gap versus Tesla anytime soon is wishful thinking,” says Patrick Hummel, UBS’s global auto analyst. “It’s a more agile organization.” By contrast, he says, “Volkswagen is a supertanker that seems to have difficulties getting things done quickly.”

For that reason alone, Diess saw Musk’s arrival in Germany as a godsend, finally injecting urgency in his own company. “It was about taking the competition from Grünheide seriously,” he says, “not seeing it as a weird, fancy startup which is going to vanish soon.” Looking out over the manufacturing complex from his office, Diess says that by 2030, “you will not recognize Wolfsburg anymore.”

The clearest sign so far of the change can be found 33 miles north of Wolfsburg, in the old iron-ore town of Salzgitter, where Volkswagen has been building combustion engines for more than 50 years. The lobby displays a 1,000-horsepower Bugatti race-car engine—a hefty chunk of steel epitomizing the ingenuity that has made automobiles Germany’s biggest export.

Yet it’s clear this is a world in transition. By 2030, not a single combustion engine will be built here. Salzgitter will be the first of six battery plants Volkswagen plans to open in Europe by then. With a combined production capacity of 240 gigawatt-hours, that will be enough to power up to 4 million EVs a year.

On one side of the half-mile-long factory, dozens of workers, many with gray hair, still build combustion engines. But on the battery-production side, the workers are fewer, and younger. There, a manager leads a small group in a training session, stopping at a display board that shows a diagram of an EV battery. At one workstation, Sebastian Schrader has already made the switch. Having begun in the engine factory at age 16, Schrader, now 42, says he raced to apply for a new EV job in 2020. Today he leads a team of 10 that shapes copper battery parts. “Everybody is happy,” he says. “There is a future path in this new world.”

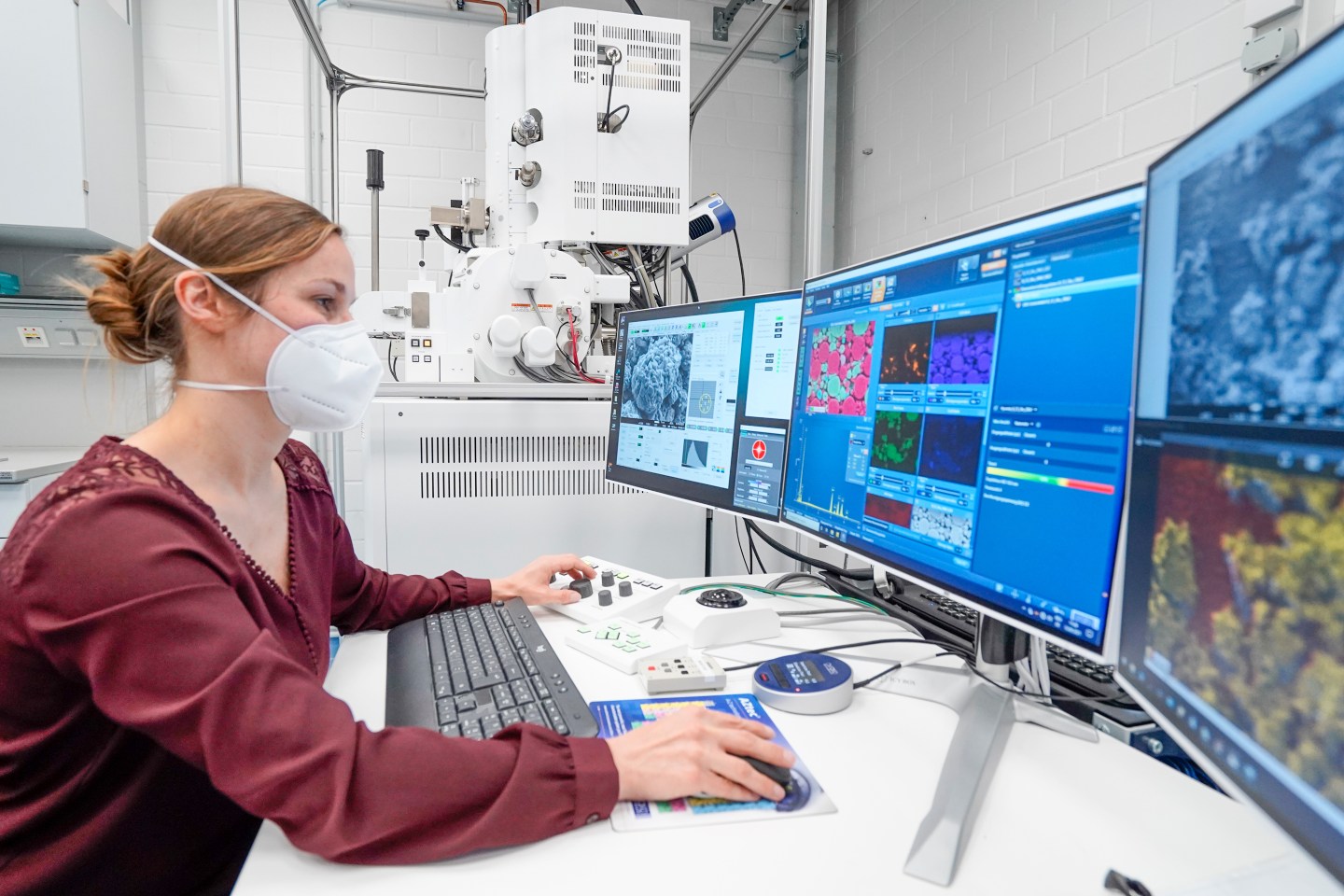

Round the side of the building sits Volkswagen’s first battery laboratory—a hushed, sterile set of rooms where engineers lean over computer monitors, working on battery designs. Nearby, a recycling operation is gearing up to extract lithium, nickel, and other metals from expired batteries in the future, to sell them on the open market.

The factory represents a step toward one of Diess’s most crucial goals: to control Volkswagen’s components, instead of relying on outside suppliers, as it has done for decades. That dependence cost Volkswagen dearly last year, as production slowed during the global microchip drought. Indeed, the Wolfsburg and Salzgitter plants were still uncharacteristically quiet in January.

Elon Musk didn’t have that problem. Having anticipated today’s roaring EV sales, Tesla long ago locked in huge supplies of microchips and raw materials. That enabled Tesla to double shipments in 2021 over the year before, despite the supply-chain crisis. And in January, Musk inked a deal to buy enough U.S. nickel to power a million car batteries a year, further securing Tesla’s grip on raw materials. Volkswagen execs admit that they struggle to be as nimble. “It is easier if you have nothing to lose, if you are starting from scratch,” says Frank Blome, head of Volkswagen’s battery development. “For us, it is a transformation.”

Having started drastically behind Tesla, the auto giants will need to not only ramp up production but also win over millions of customers. Where EVs are concerned, theirs are the unfamiliar brands. “For the majority of consumers globally, when they think of an electric car, they think of Tesla,” says Felipe Munoz, senior global analyst for JATO Dynamics, an automotive consulting firm.

In any transition, there is a danger that you underestimate your challengers.

Herbert Diess, CEO, Volkswagen

Volkswagen has made some strides with customers. Its compact ID.3 and ID.4 EVs have become a hit in Europe. Last year they were joined by an electric Tiguan SUV. Volkswagen will launch an EV version of the hippie-era microbus in Europe this summer and in the U.S. in 2023.

But Diess believes that to break through at a higher speed, the company needs extreme streamlining—a profound change in production strategy. Instead of sourcing a multitude of different components for each of Volkswagen’s 12 brands, engineers in Wolfsburg are developing a new system that will roll out in 2026 as the basis for EVs across the company. Volkswagen will be able to cut production costs by building a single electric-drive platform in-house, with fewer parts, for all its vehicles.

To match its hardware progress, Volkswagen is also racing to develop new software. Both Volkswagen and Ford have acquired stakes in Argo AI, an artificial-intelligence automotive company in Pittsburgh, which is testing driverless taxis in U.S. and European cities; Volkswagen aims to roll out its own “robo-cabs” in Hamburg in 2025.

And in 2020, Volkswagen created its own software company, Cariad, headquartered in southern Germany. Cariad’s 4,500 software engineers are tasked with developing a single operating system for all Volkswagen EVs. Such an operating system can enable vehicles to continually update—as smartphones do—with new features like shorter battery-recharge times and best driving routes. (Tesla owners are already familiar with the phenomenon.) “The opportunities are vast,” says Cariad’s new chief technology officer Lynn Longo, who previously worked on GM’s mobility software. “We will be able to layer on new experiences.”

By radically reshaping the company, Volkswagen also hopes to finally entice American consumers, who have shunned its sedans for years. Volkswagen hadn’t turned a profit in the U.S. for nine years, until 2021, when it shifted to selling mostly SUVs there. But starting this September, the company will begin producing ID.3s in its Chattanooga factory, aiming to woo a younger, EV-loving demographic. “Anytime you have a market reset, and you are one of the smaller brands, it is a chance to move to the top of the pack,” says Scott Keogh, president and CEO of Volkswagen of America. “It’s a once-in-a-generation chance.”

Indeed, from Volkswagen’s point of view, the EV battle is not only about which company sells the most vehicles. The transformation will change the very definition of what cars are, and what carmakers do. Diess admits that is a daunting change. Volkswagen’s cash flow from traditional car sales will allow it to invest billions in the EV transition, but there’s no substitute for expertise. When it comes to making batteries and software, Diess says, “We are a novice.”

Drive East from Berlin Brandenburg Airport, and a symbol of Volkswagen’s “novice” status looms into view. Off the Tesla exit on the highway, on Teslastrasse, the finishing touches are being put on Elon Musk’s sprawling Grünheide gigafactory.

On a chilly Sunday in January, the site is deserted, except for a lone security guard at the gate. It’s a far cry from the vision Musk laid out to Fortune a year ago, when he predicted the factory would be turning out 1,000 cars a week by this point. Still winding its way through German bureaucracy, the factory has yet to produce Teslas for sale. Those delays have reminded Volkswagen of some of its advantages. “We already build 10 million cars [a year],” Volkswagen’s chief financial officer, Arno Antlitz, tells me. “We have the dealerships, the factories, the processes.”

Even so, it is not yet clear that Volkswagen can replicate that vast capacity with EVs. Not only is the company scrambling to secure raw materials, microchips, and batteries, there is also a shortage of skilled people. Diess says Volkswagen is struggling to fill up to 2,000 vacancies in Zwickau, in eastern Germany, to add to the workforce of 9,000 in that factory, where it aims to produce 1.5 million EVs by 2025. Cariad’s Longo says she faces the same problem, in a “very hot industry.” The squeeze will worsen once Tesla starts production in Grünheide. “We will need probably on the order of between 40,000 and 50,000 people,” Musk told me last year.

Tesla is also not the only rival nipping at Volkswagen’s heels. China has nurtured several carmakers that produce EVs at growing scale. Two of them, XPeng Motors and Nio, now sell in Norway, for less than Tesla or Volkswagen models. In China itself, the world’s biggest car market, Volkswagen trails far behind both Tesla and Chinese companies in EV sales. “Traditional manufacturers completely underestimated the threat of Tesla,” says Matthias Schmidt, an auto industry analyst in Berlin. “Will history repeat itself with the Chinese manufacturers?” That, he says, would cost Volkswagen dearly.

Diess is determined not to repeat that mistake. He says he is keenly aware of another fateful tech showdown 15 years ago—between Finland’s Nokia, which dominated the mobile-phone market then, and Apple, whose new iPhone Nokia largely dismissed. “Well, we know who won that battle,” I say to Diess. “Yes, I am concerned,” he responds. “We have to take new competitors very seriously. But are we lost? No. We have a good chance to win this race.”

Headcount headache:

Seeking a leaner, younger VW

For years, Germany has fretted about its aging population. The median age in the country is 47, nine years older than in the U.S. One would think that a workforce steaming toward retirement would be a big headache for Volkswagen in its effort to keep producing 10 million–plus cars a year. But Germany’s demographic bulge is a “gift,” says Thomas Schmall, technology chief for Volkswagen Components.

The company employs a whopping 295,000 people in Germany alone. It likely won’t need nearly that many as it transitions toward making mostly EVs. Electric batteries have about 20 parts, compared with 2,000 in an internal combustion engine, and robots increasingly assemble cars in auto factories.

Volkswagen won’t say how much smaller its workforce might become. But in the past five years, it has retired about 23,000 workers, while creating 9,000 EV jobs. Schmall expects many more engine workers to retire this decade, bringing their average age down from the late forties to the twenties. “We will fill up again with new people,” he says.

Even the powerful autoworkers union, IG Metall, accepts the new reality. “It is clear to us electromobility will mean less work,” union spokesman Heiko Lossie says. As long as the attrition remains voluntary, he adds, the union is unconcerned.

In fact, Volkswagen’s bigger problem is finding enough qualified twentysomethings to expand the ranks of its EV workers. It has budgeted €200 million (about $227 million) for training programs, including sponsoring a coding school in Wolfsburg, where 6,000 people competed last year for the first 450 spots. One of the winners, Hendrik Lehmann, 25, says he hopes to finish his training by May, and then to intern at Volkswagen before working abroad. “It is a big opportunity,” he says. Volkswagen certainly agrees.

This article appears in the February/March issue of Fortune with the headline, “VW levels up on electric cars.”

Never miss a story: Follow your favorite topics and authors to get a personalized email with the journalism that matters most to you.