On Dec. 3, 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang walked into the Oval Office for a one-on-one meeting. The only other person privy to the conversation was the current occupant, Donald Trump. Huang later said only that they “talked in general about export controls,” and Trump said almost nothing about the meeting. But five days later, Trump and Nvidia announced an extraordinary policy shift: Rather than continue to be classified as a serious crime, sending Nvidia’s H200 chips to China was suddenly not just allowed—it was a welcome new source of revenue, with the U.S. government extracting a 25% share of every chip sold.

The deal was vintage Trump and a telling anecdote for business leaders about how the business world now works under Trump 2.0. In the first year of his second term, Trump has rewritten the government’s relationship with business more radically than any predecessor. He started by imposing new tariffs on scores of countries, scrambling business models at millions of companies big and small. He has intervened in other ways. Think of Skydance’s August purchase of Paramount, which required federal government approval; the deal went through after Paramount agreed to pay Trump $16 million to settle a lawsuit he had brought. When Netflix announced a plan to buy Warner Bros., Trump said, “I’ll be involved in that decision.” He and his family have made deals in industries heavily shaped by government policies, including crypto, defense, and chips.

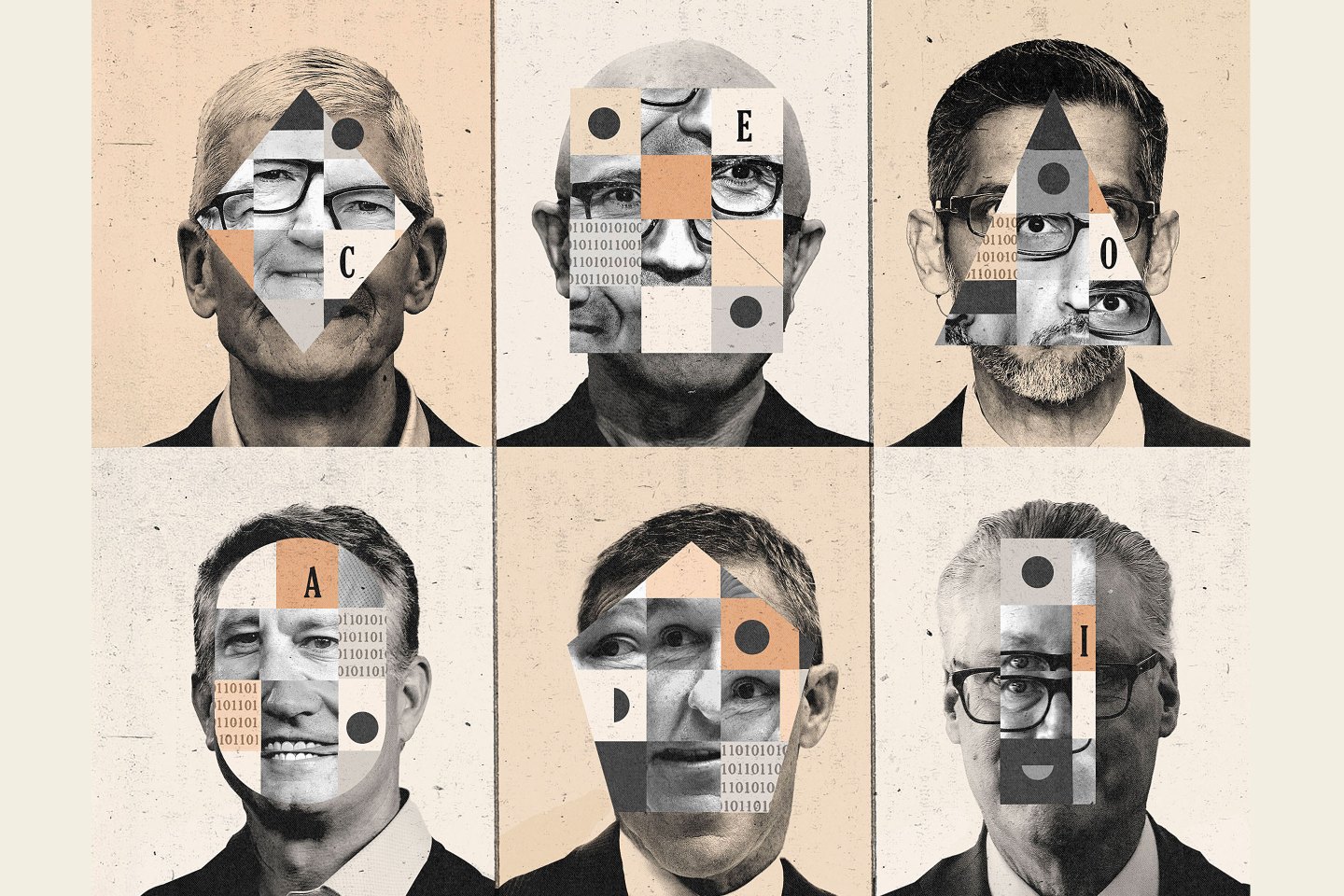

Some CEOs, especially in tech, praise him fulsomely. “Thank you for being such a pro-business, pro-innovation president,” OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said at a September dinner hosted by Trump in the White House. “It’s a very refreshing change.” Behind closed doors, Altman has said the same. Apple CEO Tim Cook said, “I want to thank you for setting the tone such that we can make a major investment in the United States and have some key manufacturing here.” Three CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, the global chair of another, and a leader of a major startup separately noted to Fortune a positive feeling toward the White House and described meetings where the president listened intently or instances where he personally called them for feedback. It’s a sea change from the Biden administration, these top executives said. “It feels like he wants us to win,” one noted.

Boeing also is a major fan as Trump talks up its aircraft in meetings with CEOs and heads of state. Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg even presented Trump with a spoof “Salesman of the Year” award during a November visit to the company’s South Carolina plant. Trump, never modest, later said, “I think I sold a thousand Boeing planes.” More broadly, business executives across the economy appreciate the administration’s cutbacks on regulations.

But when CEOs speak anonymously in surveys, they don’t seem any happier, collectively, after a year of Trump’s pro-business policies. In the fall 2024 Fortune/Deloitte CEO Survey, conducted just after that year’s presidential election, 61% of CEOs said they were “optimistic or very optimistic for my industry.” A year later, under Trump, only 47% felt that way, while those who felt pessimistic or very pessimistic more than doubled, from 10% to 22%.

Tariffs, one of the president’s signature economic innovations, were among the group’s biggest worries, with 78% saying they carried “fewer benefits than risks” for U.S. competitiveness.

In every relationship, problem, and wish, Trump can find a deal, and he revels in it.

Why the disconnect? It has a lot to do with the president’s leadership style. Though we’re only one year in, three clear themes have come to define that style. Above all, his love of one-on-one deals. Second, his practiced element of unpredictability. Finally, his penchant for grabbing the deal without sweating the details. Deals have always been inherent in politics, but Trump’s devotion to them is different. In every relationship, problem, and wish, he can find a deal, and he revels in it.

“Those who know him have been almost zealously unanimous saying the same thing,” notes someone who has known him and worked with him in real estate for many years. “He’s using the same skills, and he’s applying them to politics.”

Even at his press conference following Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s capture in early January—arguably the president’s most unpredictable move so far—Trump mused about his efforts to end the Russia-Ukraine war, and concluded, “It’s all a deal. Life’s a big deal.”

That propensity is deeply seated. It rises from his career as the third generation in his family’s real estate business, immersed in it from childhood. The Trump Organization is not like a Fortune 500 corporation. Privately held, it doesn’t report to thousands of shareholders. While it has thousands of employees, decision-making is concentrated in just a few: The head office at Trump Tower in New York is small, maybe 40 people, estimates someone who has worked with Trump for years. The company’s operations consist mostly of building, buying, selling, and leasing properties, and licensing the Trump brand—and all those activities require mostly negotiating deals.

So why does Trump’s love of the deal feel so disruptive—thrillingly so to supporters, alarmingly so to others—in his role as president?

For one thing, trust in the federal government has hovered at abysmal lows for more than a decade—due in no small part to its perceived inability to accomplish anything positive. Thanks to partisan gridlock, passing meaningful reforms takes months if it happens at all—implementing them through regulations takes years. In this stale atmosphere, Trump-style deals can feel liberatingly fresh; they can be done with an hour-long one-on-one and a handshake. (No coincidence, perhaps, that many in tech’s venture and startup worlds have warmed to Trump: He’s a move-fast-and-break-stuff guy.)

Just as important, unlike with many laws and regulations, deals usually give at least one party a quantifiable financial win. (Trump, needless to say, wants to always be that party.) On the economic and trade fronts, the Trump administration repeatedly leaves the table with a tweetable return on investment—$30 billion a month in tariff income, $100 billion in new Apple factories, a 10% stake in Intel.

“He sees these deals as trying to enrich the federal government as if it were a business.”

In a world where anxiety about the federal debt is widespread and bipartisan, these revenue announcements play well, including with business leaders who are required to be good financial stewards and wish the same were true of the government. They also carry extra weight with Trump’s blue-collar political base. Trump has tapped into many of those voters’ belief that multinational companies and trade partners have cheated them out of their chance at prosperity. When the president announces a favorable deal with a foreign trade partner or a big corporation, it can feel like payback, especially when it comes with a promise of billions of investment in the U.S.A.

Without question, Trump’s policies are taking the government—and business—in directions they have never gone before. He’s doing so, as he’s done for years, with a steamroller-like disdain for legal and cultural norms— showing no hesitation about threatening or punishing critics, and dismissing complaints about policies that reward his donors and industries in which his own family has business interests. And what makes the current moment even more fascinating, and fraught, is that, roughly one year in, it’s still too early to tell whether all of this glass-shattering is working—or whether it’s sustainable.

To understand Trump’s unprecedented style of carrying out presidential duties, it’s necessary to know his revelations about himself. In a 2019 interview with Bob Woodward, he said, “My whole life has been deals…I’ve made unbelievable deals—from very little, made great deals. That’s what I do.” And in his 2015 book Crippled America: How to Make America Great Again, he explained a key element of his dealing style: “I don’t want people to know exactly what I’m doing—or thinking. I like being unpredictable. It keeps them off balance.” Those intertwined tenets illuminate much of how Trump operates as president.

Especially important to businesspeople, and especially unusual in the context of government, is Trump’s propensity to get involved with individual companies. Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla recalls his frequent talks with Trump in his first term as Pfizer worked on developing a COVID vaccine. “He would call me every week,” Bourla says. “It was constant.” When Trump returned to the White House in 2025 they resumed conversations, and “he was adamant that he can’t tolerate other nations paying less than Americans pay for medicines,” Bourla recalls. “I came to the conclusion that we needed to cut a deal.” The deal, Bourla says, took just 10 days to reach. Pfizer became one of nine pharmaceutical companies that have agreed with the government to reduce drug prices.

Often these conversations have the tone of CEO to CEO—the kind of interpersonal ground on which so many business deals are built. “The Nvidia deal is more evidence that he sees the government as his business,” says Jessica Riedl, a fellow at the Brookings Institution who worked on the presidential campaigns of Mitt Romney and Marco Rubio. “He’s trying to increase the size of his system rather than focus on public policy and what’s best for the economy. He sees these deals as trying to enrich the federal government as if it were a business. It’s a very unique way of looking at his job compared to other presidents.”

Whether the tools Trump is using are the right ones to fix the country’s largest problems remains to be seen. He has proposed an enormous increase in the defense budget, for example, asserting that aggressive trade policies will pay for it. Tariffs have indeed brought in significant revenue; they reduced the fiscal 2025 budget deficit by about 10%, with tariffs in force for only half the fiscal year. But the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget says tariffs will not come close to matching Trump’s proposed defense budget over the next decade, and government debt will continue its unsustainable rise.

Fortune/Deloitte CEO Survey

Optimistic or very optimistic for my industry

61%

Fall 2024

47%

Fall 2025

Pessimistic or very pessimistic for my industry

10%

Fall 2024

22%

Fall 2025

This new Trump 2.0 frontier presents important and strange new questions. Exhibit A: the Nvidia deal’s requirement that Nvidia pay the Treasury 25% of its revenue from selling H200 chips in China. The Constitution prohibits any “Tax or Duty” on exports, which this deal would appear to violate. Erik Jensen, a law professor emeritus at Case Western and an expert on the Constitution’s Export Clause, tells Fortune there’s no way around it: “The Export Clause is an absolute prohibition, not a recommendation.” (The U.S. Commerce Department did not respond to a request that it explain how the 25% charge will be handled.)

But does anyone care? “Who would have standing to challenge the charge [in court]?” the professor asks. Certainly not Nvidia, he says: “Nvidia is apparently happy with the deal.”

In some of Trump’s deals the purpose is unclear. “For most of us, a trade or deal is a means to an end,” says Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former director of the Congressional Budget Office and now president of the American Action Forum, a center-right advocacy group. “In many cases, it feels to me like, for him, the deal is the end. Making a deal is the joy.”

Example: Nippon Steel’s purchase of U.S. Steel, which the Biden administration had blocked, in part because the United Steelworkers union strongly fought the sale. Trump had opposed it also, but in June he changed his mind, subject to all parties’ agreement to an unusual demand. Without the U.S. contributing money, he and future presidents would hold extraordinary secret powers over the company—a so-called golden share. Those secret powers, as uncovered by the New York Times, include total say over all the board’s independent directors and vetoes over locations of offices and factories. The White House justified the golden share as protecting “national and economic security,” but the government already wields multiple tools for that. Trump didn’t need to make a deal, but he made one anyway.

Across the economy, the U.S. bought equity stakes or options for equity in nine companies in 2025, an unprecedented reach of the federal government into business ownership. Economists have long disfavored such arrangements because they leave the company open to political favoritism and pressure, and they expose taxpayers to risks if the company doesn’t succeed.

It’s not clear what upsides counter those downsides. For example, the U.S. in 2025 signed a contract to buy all the rare earth magnets made by MP Materials, which mines rare earths in California, for 10 years at a preferred price. The government also spent $400 million on a majority stake, but why? “We need rare earths, we get rare earths” from the contract, Holtz-Eakin says. “I don’t know what the equity stake does. But here, it’s always ownership stakes.”

But the stakes trend may betoken a new model of the government’s relationship to business—one in which Uncle Sam tries to capture a measurable ROI when it pursues industrial policy. After Trump’s deal with Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan to buy equity, Kevin Hassett, director of the National Economic Council, said, “I’m sure there’ll be more transactions.” A guiding strategy has not been advanced—unless the stake is the strategy. “It all comes down to control and wanting more of the revenue of these businesses,” Riedl says. “It’s what you would expect from a businessman trying to negotiate a larger profit from a deal.”

Trump’s preference for negotiating deals with one person, face-to-face, extends to government leaders. Think of all the heads of state who have met with him alone, sometimes with an aide, sometimes not—Ukraine’s Zelensky, South Africa’s Ramaphosa, Canada’s Carney, and others in the Oval Office, plus Russia’s Putin in Alaska. But one-on-ones can be awkward for a president because most policy shifts require multiple players.

Consider, for example, Trump’s largest project so far, his transformation of America’s tariffs. Historically, tariff negotiations “have been regional or multilateral complex negotiations involving multiple countries and multiple interests,” says Edward Alden, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. But that’s not the kind of deal Trump does. “Most business dealings are bilateral,” Alden says, “and that’s what he’s comfortable with.” Now, in his second term, “you see that he is trying to reduce every international negotiation to a bilateral deal.”

Trump’s “Liberation Day” list of tariffs in April included 185 countries, and the majority of them, with the large exception of China, have negotiated deals with mostly minor changes—but the U.S. has bargained individually rather than with regional trade blocs. Even when negotiating changes in the trilateral U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, Trump has so far met with the two countries’ leaders separately, not together.

Trump’s many one-on-one deals—such as with Jensen Huang—may evaporate when he is no longer president.

America’s international relations beyond tariffs are a similar picture. Rather than try to work with European countries to settle the Ukraine-Russia war, for example, or even bring the Russians and Ukrainians together, with the U.S. as mediators—strategies the U.S. has used before in different settings—Trump has essentially tried to do bilateral deals with each side, Alden says. The approach has yet to succeed, despite candidate Trump’s promise that he could end the war in 24 hours.

Elsewhere, Trump is applying his favored keep-’emguessing penchant to America’s most important global relationships. Using overwhelming military power in Venezuela has lately been the biggest move (and one that the president pitched as having, of course, an ROI, in which the U.S. government will sell Venezuelan oil on global markets). That transactional mindset in international relations “has always existed, but just as a part of international diplomacy,” Alden says. “He has made it pretty much everything.”

Beyond dealmaking, how has Trump fared on the managerial front? The broadest example is his high-profile and often chaotic rush to downsize the executive branch. By the numbers, he succeeded: The federal workforce is some 270,000 fewer than when Trump was sworn in. But research by the Brookings Institution finds that many agencies that fired hundreds or thousands of employees are rehiring them: Government agencies are listing thousands of jobs on internet job boards, and hundreds of lawsuits on firings and agency eliminations are winding through the courts. The Department of Government Efficiency, DOGE, which led the project under Elon Musk, no longer exists as a centralized entity.

One thing is clear overall: The dealmaker presidency is unpopular with many voters. In an October Washington Post survey, 63% disapproved of Trump’s “handling of the federal government.” His approval rating has fallen faster and further in his first year than that of any other president in recent times.

Trump’s lifelong three-part operating system—skillful one-on-one deals plus unpredictability and pushing ahead while others work on the details—has served him well. He’s rich and he’s president. But his system may not be ideal for solving the largest problems at the apex of power in the world’s wealthiest nation, says Peter Feaver, a political scientist at Duke University who held positions in the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations. “If the challenge requires the president to make a break with tradition, to say something no one else has said, or make an offer no one else had the guts to make, that’s Trump’s strength,” Feaver says. “But if it requires working with lots of partners, pulling together a coalition of the willing on your side, and a capacity to think two, three, four steps down the game tree—that’s where he has struggled.”

No number of one-on-one negotiations, for example, will stop the national debt from growing faster than the economy. The government’s largest expenditure, Social Security, is on track to drain the last dollars from its trust funds in 2033. In the 1980s, a 15-member bipartisan commission rescued Social Security by agreeing on several technical changes. That process was slow, undramatic, and involved a lot of hairsplitting compromises. It was more like governing than dealmaking.

The past year also suggests Trump’s legacy of governing may be surprisingly ephemeral. He finds legislation slow and tiring, preferring to govern through hundreds of executive orders, but they can be revoked by any president to follow. The substance of his many one-on-one deals—such as with Nvidia’s Huang—may evaporate when he is no longer president. His agreements with leaders of nations could likewise disappear because those deals aren’t treaties, signed by Trump and ratified by the Senate.

In 2017, Trump became the first U.S. president with no experience in paid government work, including in the military. Business is his world. But ultimately, “running a country is not about making money,” says Heidi Crebo-Rediker, the U.S. State Department’s chief economist in the Obama administration and a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. “And even if Trump wants to run the country like a business, it’s not a CEO job.”

Donald Trump, the world’s most famous CEO, clearly disagrees. And to tackle the thorny financial and economic crises the nation faces, more business acumen and strategic thinking in government could be a valuable asset. But President Trump’s job, unlike a CEO’s, is subject to the Constitution, elections, and a 535-member board of directors, and it demands that the president deliver benefits to an even bigger group of stakeholders: all Americans. Those diverging missions, which put business and government in eternal contention, have over time served the country extraordinarily well.

Bottom line: Great CEOs can be American heroes, but it’s not yet clear if history will bestow that distinction on presidents who think they’re CEOs.

Nine extraordinary deals

April 2: Tariffs

Trump imposes “reciprocal tariffs” on 57 countries, with each tariff understood as an opening bid in a negotiation. Several countries have since made deals. The one-on-one negotiations, unlike the multilateral system of the past 80 years, can be chaotic for companies and economies.

June 13: U.S. Steel “Golden Share”

In return for allowing Nippon Steel to buy U.S. Steel, Trump requires that the U.S. receive several powers over the company, including total power over all the board’s independent directors and vetoes over locations of offices and factories.

July 10: MP Materials

The U.S. pays $400 million for a large equity share in MP and signs a contract to buy all of MP’s rare earth magnets for 10 years. The reason for the equity stake was not disclosed.

July 14: Nvidia, Part 1

Trump reverses the U.S. ban on selling Nvidia H20 chips to China in exchange for Nvidia paying the U.S. 15% of the revenue.

July 23: Columbia University

The Trump administration restores $400 million of canceled federal research funding for the university under an unprecedented multipoint deal. For example, Columbia must supply data to the federal government for all applicants, broken down by race, “color,” GPA, and standardized test performance. A few other schools later make similar deals.

August 6: Apple

At a public appearance with Trump, CEO Tim Cook announces Apple will invest an additional $100 billion in the U.S. over four years; Trump announces Apple will be exempt from a planned tariff on imported chips that would have doubled the price of iPhones in the U.S.

August 22: Intel

Intel trades the U.S. government a 9.9% equity stake in exchange for $8.9 billion that might already be owed to Intel under the CHIPS and Science Act. The deal is unusual because the company was not in immediate danger or significantly affecting the economy.

December 8: Nvidia, Part 2:

Trump reverses the U.S. ban on selling powerful Nvidia H200 chips in exchange for Nvidia paying the U.S. 25% of the revenue. Both Nvidia deals are unusual because the payments to the U.S., based on exports, appear to be forbidden by the Constitution.

December 19: Pharma

Nine pharmaceutical companies make deals with Trump that are intended to lower drug prices. This is unusual because Trump negotiated separate deals with each company, and the terms have not been released.

This article appears in the February/March 2026 issue of Fortune with the headline “USA Inc.”