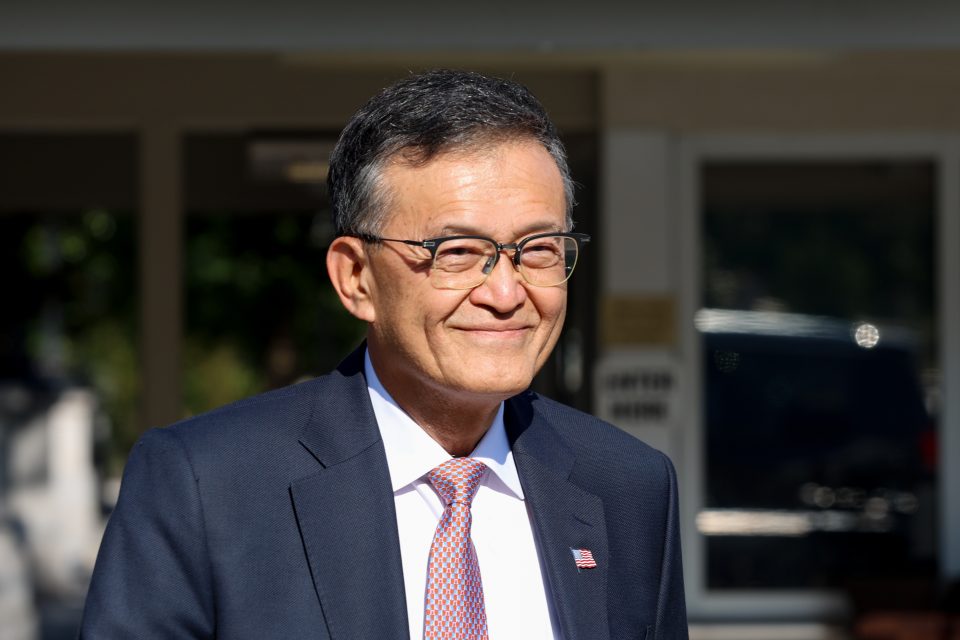

It certainly wasn’t the savior’s welcome Lip-Bu Tan may have expected. It was March 2025, and he had just been named Intel’s CEO, lured back after resigning from the company’s board of directors seven months earlier. Intel was drifting, overseen temporarily by two executives after the previous CEO abruptly retired. Now, for the first time, Tan was addressing online all Intel employees globally. They were looking for straight talk—and if they felt they weren’t getting it, the Intel culture would let them say so.

“You’re allowed to ask whatever you want in our company and not feel any ramifications from that,” a recently retired 30-year employee tells Fortune. Tan “was immediately asked, ‘Why did you quit [when he resigned from the board]—and now you think you’re going to come back and save us?’” Tan’s answer that he was dealing with personal things did not assuage the crowd. The veteran employee says side chats immediately lit up with criticism. “They were very frustrated with his answer.”

If Tan was sweating then, the heat cranked up considerably in August, when Arkansas Sen. Tom Cotton alleged that Tan controlled Chinese companies and had a stake in hundreds of Chinese technology firms, some of which reportedly had ties to the Chinese army. President Trump quickly posted on Truth Social that Tan “is highly CONFLICTED and must resign.”

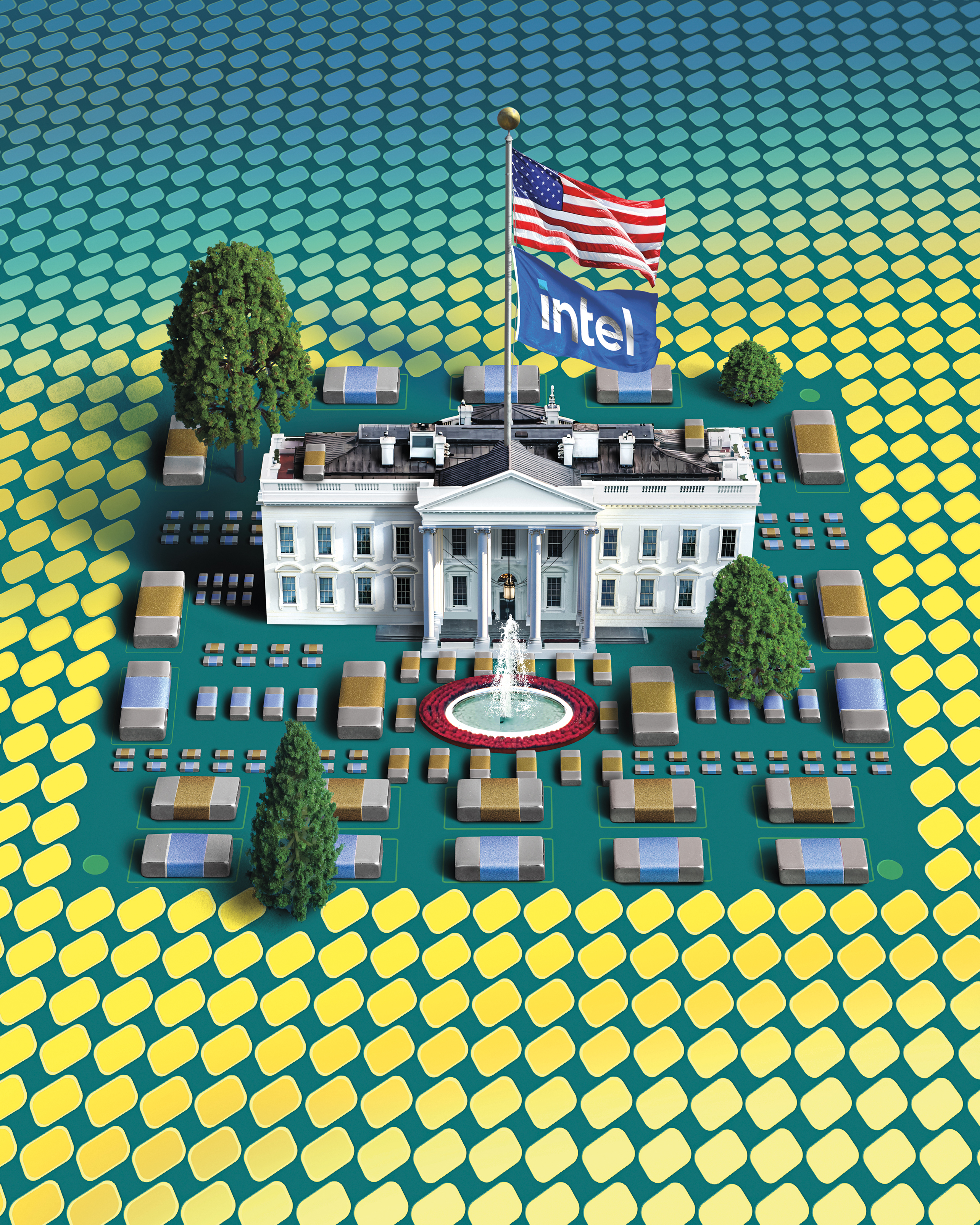

Yet after Tan met with Trump four days later, the winds started to shift for Intel. The two seemed to hit it off, and not long thereafter they struck a nearly unprecedented deal: Intel would send 9.9% of its stock to the federal government, and the U.S. would convey $8.9 billion to Intel. Then, in late September, the world’s most valuable company, Nvidia, agreed to invest $5 billion in the chipmaker. Under their agreement, Intel will produce a broad range of new chips combining technology from both companies, with Nvidia buying some of the chips.

Craig Barrett, a former Intel CEO, told Fortune recently that this model—customers putting new capital into the company—could save Intel, which desperately needs cash. “The only place the cash can come from is the customers,” he says. “They are all cash-rich, and if eight of them were willing to invest $5 billion each, then Intel would have a chance.” In addition to Nvidia, those companies would likely include Apple, Broadcom, Google, Qualcomm, and a few others that might want a second source of high-value chips that are otherwise available only from TSMC, the Taiwan-based chipmaker that is the world’s largest.

Intel, a once-great company, seems to have found itself a plausible shot at redemption. Depending on how its leaders execute, it will go down in history as a turnaround for the ages or a case study in mismanagement and government overreach. Either way, it will also be much more—because without anyone intending it, saving Intel isn’t just vital for the company’s stakeholders. Its survival will have a profound effect on America’s national security.

In the digital era, the national security of a great power requires a reliable supply of leading-edge semiconductors, yet virtually all of today’s leading-edge chips are made by TSMC in Taiwan, with others made by Samsung in South Korea. The Pentagon quietly buys lots of those chips because it can’t get what it needs in the U.S. Many people might be surprised to learn, for example, that America’s F-35, the world’s most advanced fighter jet, requires TSMC chips. “We do not want to overstate the precariousness of our position,” wrote the leaders of the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence in 2021, “but given that the vast majority of cutting-edge chips are produced at a single plant separated by just 110 miles of water from our principal strategic competitor, we must reevaluate the meaning of supply-chain resilience and security.”

To give the lay of the land, there are plenty of chipmakers around the world that can manufacture the type of commodity chips that run, say, your car, TV, refrigerator, and countless other products. John Neuffer, CEO of the Semiconductor Industry Association, likes to say that if something has electricity going through it, it probably has a chip.

Intel makes a wide range of far more sophisticated chips—those used in PCs, workstations, servers, cloud computing, parts of AI computing, and much else. It is also working to manufacture in volume an advanced chip called 18A, and crucially, it is trying to produce an even more advanced chip called 14A. Intel makes chips in Arizona, Oregon, Ireland, and Israel, with other operations to create the finished product in locations around the world.

But TSMC, Samsung, and Intel are the only companies in the world capable of manufacturing leading-edge chips—the highly technical chips the Pentagon and AI hyperscalers need. Intel hasn’t actually made any such chips since 2017. The company fell behind its competitors gradually, yet even now it owns the requirements to get back in the game: multiple fabs plus huge ones under construction, the latest manufacturing equipment, and much of the required unique know-how. It could take years for Intel to get back in the game—14A production wouldn’t occur until 2027 at the earliest. But it would be decades for any plausible rivals to emerge to manufacture these unimaginably precise products.

How America’s leading maker of chips, a pioneer of Silicon Valley, got to this dark place was by missing not just the next big thing, but the next big things. After its glamour years furnishing chips for personal computers in the 1990s, Steve Jobs wanted Intel to make chips for Apple’s iPhone when that was just a concept, but the company declined. The company never created a successful graphics processing unit, a type of chip then used for games but now adapted and used for Nvidia’s world-changing AI chips, which are manufactured entirely by TSMC. In the 2010s Intel declined steadily under a series of wrong CEOs. Revenue peaked in 2021 and has fallen sharply since. Wall Street analysts project this year’s revenue will decline again.

Intel will need a ton of money from outside sources. How much? “They probably need a cash infusion of $40 billion or so,” says Craig Barrett, Intel’s CEO from 1998 to 2005.

The board, seeking a new CEO in 2021, desperately brought back Pat Gelsinger, a 30-year Intel executive who had left years earlier. “Everyone was really jazzed when he came back,” a former longtime employee in project management tells Fortune. “We thought, ‘Okay, finally we’re going to get back on track.’” Gelsinger described an ambitious plan of building new fabs and again making leading-edge chips. He also worked hard to get the CHIPS and Science Act through Congress and signed into law. “I would argue it’s the most important piece of industrial policy legislation since World War II,” he told Fortune last year. The law gave money to scores of companies that make chips or provide goods and services for making chips in the U.S. Foreign companies, including TSMC and Samsung, got billions of dollars to help build U.S. fabs—but Intel got more than any other company

The Chips Act was all about national security. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, who oversaw most of the program, explained, “We cannot allow ourselves to be overly reliant on one part of the world for the most important piece of hardware in the 21st century.” But the law was never meant to finance any company’s projects fully, and some of Intel’s directors reportedly got nervous about Gelsinger’s expensive widespread projects—two vast new fabs in Arizona, one in Ohio, others in Europe. Investors eventually lost confidence also; during his tenure the stock plunged, down 66% by last December, when the company announced his retirement.

Tan publicly gave no reason for leaving the Intel board in August 2024. But when he became CEO, reining in Gelsinger’s investments was near the top of his agenda. As he later told employees, “There are no more blank checks.”

Today seemingly no one at Intel denies the company is a rescue project. “Intel has a lot of work to do in catching up and participating in the AI transformation,” says Sachin Katti, Intel’s chief technology officer and AI leader, a Stanford professor who came to Intel three years ago. One of his top priorities is “reinvigorating the engineering and technical culture that made Intel really successful. Intel needs to rebuild the momentum it seems to have lost over the past few years.”

The problem is that Intel must transform a downward spiral into an upward spiral, which is rarely easy. For most of the company’s life it attracted some of the world’s most brilliant engineers and scientists. But as the company declined, it became less alluring to the world’s brainiest 1%. Now Intel is turning a bug into a feature. The pitch: If you come to Intel now, “you’re not joining the company at its highest,” Katti says. “You’re joining it to build it back to its glory days. People who enjoy such a challenge and are deeply technical—that’s who I’m recruiting.”

Another ditch Intel must climb out of is financial. S&P Global in December downgraded Intel’s credit to the lowest investment-grade rating, BBB, with stable outlook; more recently, Fitch in August downgraded it to BBB with negative outlook. Institutional Shareholder Services’ financial assessment business, ISS EVA, which covers 28,000 businesses globally, puts Intel’s overall financial quality in the fifth percentile. Bennett Stewart, a longtime corporate finance expert, expresses amazement at how much money was shoveled out the door during the Gelsinger years. “They had been trying to spend their way out of their problems, not successfully at all.”

The trend is changing diametrically under Tan. “We’re being more fiscally conservative,” says CFO Dave Zinsner. The new stance starts with selling assets to pay off debt. Tan almost immediately decided to sell a 51% stake in Intel’s Altera programmable chip business for $3.5 billion, a deal expected to close soon. Intel has also sold $1 billion of its stock in Mobileye, a developer of autonomous driving tech. In addition to asset sales, more cash is scheduled from SoftBank, which plans to buy $2 billion of new Intel stock.

Tan is also cutting costs deeply. He has postponed Intel’s giant Ohio fab project and canceled planned factories in Germany and Poland. In July he said 15,000 layoffs will be completed by year-end; the move will halve Intel’s incredible 11 layers of management.

It’s all preparing the ground for production of leading-edge chips once again. But to do that, even after Tan’s much needed belt tightening, virtually everyone inside and outside the company agrees on one thing: Intel will need a ton of money from outside sources.

The Nvidia investment in late September is a start, but Barrett, Intel’s CEO from 1998 to 2005, thinks “they probably need a cash infusion of $40 billion or so.” Gelsinger, now a general partner at the Playground Global venture capital firm, argues for a U.S. sovereign wealth fund, noting that China bankrolls many companies developing strategically important technologies.

But customers are the most likely source, argue Barrett and David Yoffie, an Intel director from 1989 to 2018 and a Harvard Business School professor. Yoffie notes that “$5 billion apiece for those companies is not a lot of money. It would be spread over a couple of years—relatively small amounts compared to what they’re already spending at TSMC.” Intel has even set up the manufacturing business as a subsidiary to make it easy for customers to buy in as investors.

Just one problem. “It all hinges on whether they can execute the process,” says Stacy Rasgon, an analyst at Bernstein. “Process” is the industry’s term for all the steps in making a chip. “What customer is going to bet their future on Intel if they’re not 100% confident that Intel can deliver?” Specifically, Intel must prove it can deliver leading-edge chips in high volume, on time, at spec, at acceptable cost. “That’s table stakes,” says Rasgon. Intel must also clear an extra hurdle: its own reputation for poor performance. As Rasgon notes, “Betting on their failure has been a pretty good bet for the last 10-plus years.”

Intel must also clear an extra hurdle: its own reputation for poor performance. “Betting on their failure has been a pretty good bet for the last 10-plus years,” notes Bernstein Analyst Stacy Rasgon.

CFO Zinsner says several customers think being investors “might make sense,” but for now those customers are focused on the technology of the 14A chip—specifically, “what adjustments we need to make the technology better for them.” Eventually Intel will make test chips that customers can put through their paces. Best-case scenario is that Intel breaks even on making 14A by the end of 2027, as Zinsner says Intel believes it can do. But Intel acknowledges that maybe 14A won’t ever work financially. Deep in the company’s latest quarterly report filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Intel says if it can’t find at least one big customer for 14A and can’t “meet important customer milestones” for it, “we face the prospect that it will not be economical to develop and manufacture Intel 14A and successor leading-edge nodes.” (“Node” means a specific generation of chip technology.) If that happens, “we may pause or discontinue our pursuit of Intel 14A and successor nodes.” In which case, Yoffie says, “We’re never going to have an American producer making leading-edge processing in the United States probably ever again.”

Looming over Intel’s future is the complicated issue of national security. When asked about the U.S. investing in Intel, William Megginson, a University of Oklahoma professor who has researched governments taking equity stakes in private companies, speaks for most economists: “It’s almost always a bad idea. Across time, across countries, it usually does not turn out well.” Douglas Rediker, a lawyer and economist with long experience in global finance, asks skeptically, “Are we now in an era in which the U.S. government is literally picking national champions?”

But many experts in the foreign policy world say a national champion is exactly what America needs. “Supporting Intel today is not about protecting one company for its own sake,” write researchers at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C., think tank. “It is about securing the industrial base necessary for national security in an era of geopolitical competition. The alternative—a U.S. future dependent on foreign sources for the most advanced chips—is strategically untenable.”

Intel as a business could likely limp along without 14A. But for America, giving up on leading-edge chips would be going down a dangerous path.

This article appears in the October/November 2025 issue of Fortune with the headline “The battle to save Intel.”