“‘Cause I don’t think that they’d understand,” Johnny Rzeznik of the Goo Goo Dolls wailed plaintively in “Iris,” which dominated charts from April through July of 1998. He was singing about Nicolas Cage and Meg Ryan’s angel/human romance in “City of Angels,” but nearly 30 years later, he was singing to millions more, many of them Gen Z.

Google Trends’ September 3 newsletter reported that search interest for “iris goo goo dolls” was at a 15-plus year high, and as of the past week it was “the top searched song of the summer.” On Spotify, it was a top 25 global hit for several months running, The Wall Street Journal reported in late August, even reaching as high as No. 15. This phenomenon isn’t just a quirk of algorithms or chance—it’s the product of a larger cultural moment driven by nostalgia and the shifting ways we connect with music. Gen Z, a generation already defined by a keen sense of nostalgia, has popularized the concept of a “90s kid summer,” harkening back to a time before social media and smartphones—the exact time of the Goo Goo Dolls’ biggest-ever hit.

The viral surge of “Iris”

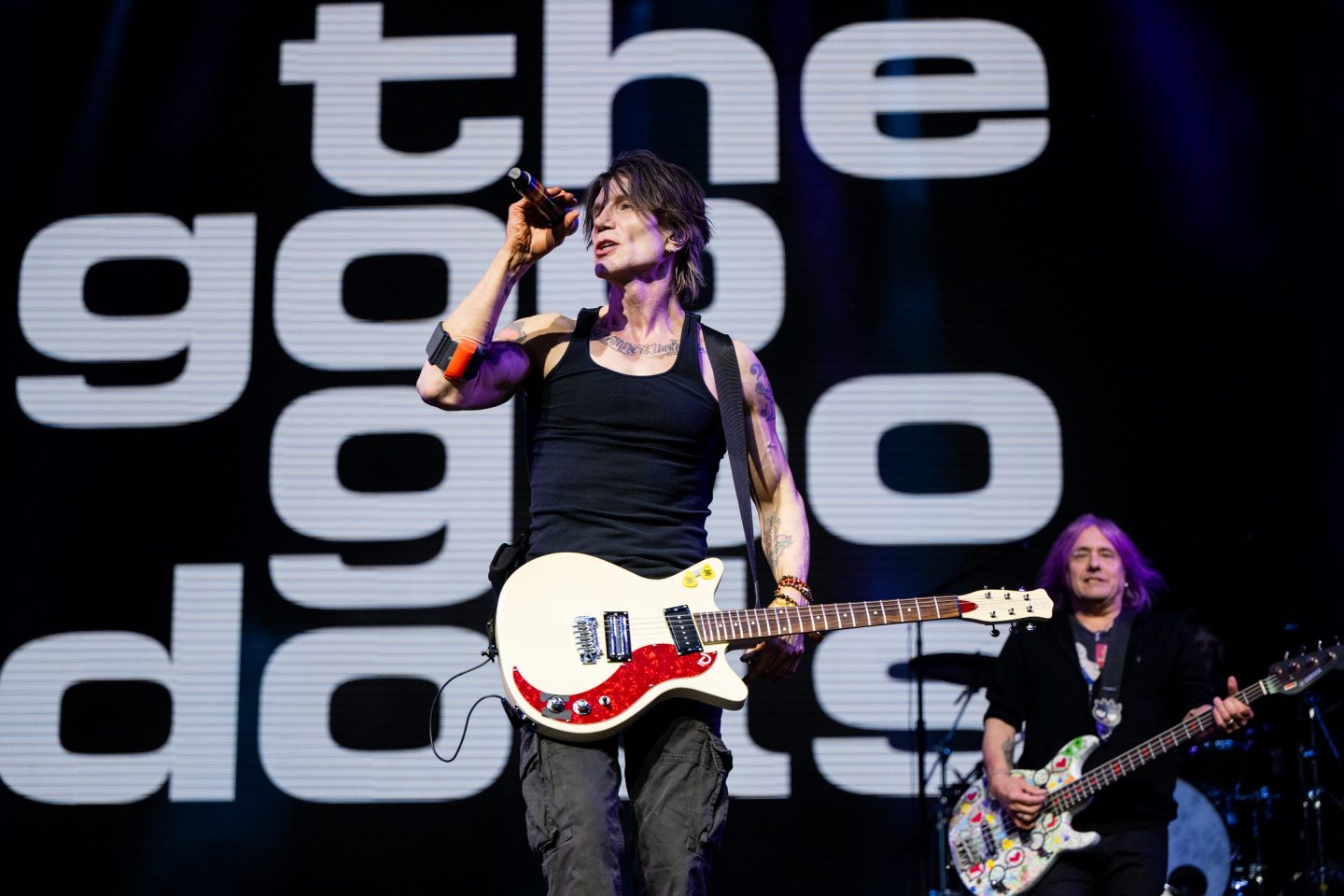

Much of the song’s renewed momentum can be traced to viral moments, such as the Goo Goo Dolls’ live performances at major festivals like Stagecoach and on the American Idol season finale. TikTok trends featuring both original footage and covers have also propelled “Iris” to new global streaming peaks, with over 5 billion streams worldwide, far and away the top result for the band on Spotify. Rzeznik told Australian outlet Noise11 that his band has to play live and “that’s how we earn a living.” With “Iris” at the 2-billion stream mark at that point, he added, “You make crap for streaming. People stream your songs and you make no money.”

John says, “Nobody makes any money out of selling records anymore because nobody buys records anymore. You make crap for streaming. People stream your songs and you make no money. You’ve got to go out and play live. That takes a lot of time. I just think the business has changed so much. Its not as much fun as it used to be. We get to play live and that’s how we earn a living”.

The strange power of a three-decade-old song dominating summer playlists is no accident. As revered music critic Simon Reynolds explored in his influential 2010 work Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past, we live in a time where cultural production is increasingly fixated on recycling the old rather than inventing the new. Reynolds argued that contemporary pop is less about innovation and more about revisiting previous decades, blurring distinct eras, and nibbling away at the present’s identity. He’s far from the only cultural theorist to spot the lure of the recycled hit.

A few years later, in 2014, the cultural theorist Mark Fisher (who later committed suicide after a long battle with depression) released a book of essays, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Among several memorable phrases, he introduced the concept of the “slow cancellation of the future”: the persistent feeling that time is repeating itself and new ideas are stalling in favor of familiar comfort. According to Fisher, our cultural imagination is increasingly drawn to recycling past successes, not just in music but in film, fashion and art. The result is a present haunted by the ghosts of earlier decades—where the future has faded into a “recycled present” and our ongoing search for novelty is often satisfied by what we already know.

Gen Z’s 1990s nostalgia

These ideas play out most vividly in recent consumer trends, especially among Gen Z. For many, the 1990s symbolize an era before smartphones and constant connectivity—a time when summers consisted of bike rides, ice cream trucks, and garden hoses, rather than endless notifications and screen time. The “90’s kid summer” trend reflects a longing for unstructured play and analog fun, with parents and young adults alike trying to recreate the freedom and creativity they associate with the pre-digital age.

Google Trends reported that “90s summer” reached an all-time high in June and “90s kid summer” was a breakout search in July. It has close similarities to a similar breakout search: “feral child summer,” which encourages parents to stop tracking their kids’ every movement (with technology that was not available in the ’90s). They communicate a yearning for another time with less technology, when “Iris” was playing on a loop over and over on VH1. For Gen Z, who never truly experienced the ‘90s but grew up with its influence, revisiting this past through music like “Iris” is both escapism and rebellion against the anxieties of the digital present.

When the Goo Goo Dolls, with opener Dashboard Confessional, played Berkeley’s Greek Theatre in September, the emo band’s frontman Chris Carrabba remarked on all the teenagers who were rocking vintage band tees in the crowd. ““Do they even have MTV anymore?” he asked in onstage comments reported by SF Gate. Then he offered an explanation to his audience: “Families used to watch TV communally. It was like large format TikTok.” SF Gate noted that the crowd grew overhelmingly loud for the closing number of the show: of course, “Iris.”

Nora Princiotti of The Ringer argued on September 3 that the summer of 2025 lacked a defining “song of the summer,” with recent examples including “Old Town Road” and “Despacito” and older classic including “Hot in Herre” Nelly and “Summer Nights” from Grease. She argued that it was a summer “without monoculture,” depriving many contenders from the chance to dominate the airwaves that were available to the Goo Goo Dolls the first time around, in 1998.

But somehow, “Iris” managed to dominate a different kind of airwave in 2025, emerging as a juggernaut in a manner oddly fitting for a world where Reynolds’ prophecy of retromania is truer than ever. If Mark Fisher was also correct that the future has been canceled, then another Goo Goo Dolls’ lyric, from their 1995 smash “Name,” also comes to mind: “reruns all become our history.”