On Monday, Feb. 17, Ed Bastian was at his condo in Deer Valley, Utah, with his fiancée, his youngest daughter, and her boyfriend, enjoying the final leg of a skiing getaway on Presidents’ Day weekend. The Delta Air Lines CEO was in a celebratory mood, still pumped from his company’s 100th anniversary party in January and from cheerleading at Delta’s annual Valentine’s Day bash—where he and his employees had partied Mardi Gras–style to toast the airline’s big annual profit-sharing distribution.

Around noon, an “emergency response” text flashed on Bastian’s iPhone. “My first reaction was that it was a drill,” Bastian tells Fortune. That wouldn’t have been unusual: Delta frequently stages surprise test runs in which flight crews rehearse rescuing passengers from accidents, while looping in top managers, Bastian included, to practice their own emergency protocols.

But when Bastian read the message again, he says, “I realized it was a real accident.” A call to his head of safety revealed the truth: A Delta plane had crashed on landing and was sitting upside down on the tarmac at Toronto Pearson International Airport.

For the leader who had helped guide Delta through 9/11, bankruptcy, and the COVID pandemic, this was a trial like no other. Delta hadn’t suffered a crash that caused fatalities in Bastian’s entire 26-year career there. “Undoubtedly that first hour was the toughest moment I’ve spent as CEO,” Bastian says. “I went from the highest of highs to the lowest of lows. You just feel helpless.”

Bastian could only visualize the “terrible event”: Photos and videos wouldn’t go viral until the next morning. But over the next 60 minutes, by phone, Bastian’s team gave him the play-by-play of a remarkable rescue effort. Delta crews safely evacuated the 76 passengers who’d been dangling upside down, held by their seatbelts; there were, miraculously, no deaths. Recounting those dramatic minutes, Bastian praises the alacrity of the flight attendants who swung into action; the speed of the ground crews that doused the burning hulk; even the “strength and flexibility of the seats” on the plane.

The cause of the crash is still under investigation. The CRJ-900 en route from Minneapolis landed amid 40 mph gusts; it appears that it lost part of its landing gear upon hitting the runway, skidded, rolled, and flipped over. Images of a giant charred metal tube lying upside down seemed like a potentially crippling blow to Delta’s burnished brand. The safety first responders had stepped up; now it was Bastian’s turn.

The CEO quickly turned the narrative to the incident’s positives. In an interview on CBS Mornings two days after the crash, Bastian declared that “the crew on board performed heroically but also as expected, as we train for this continually.” Questioned by host Gayle King about whether recent job cutting at the Federal Aviation Administration “impacts safety,” Bastian responded that “the cuts do not affect us,” adding that the Trump administration had assured him it was committed to “modernizing the skies and hiring additional air traffic controllers.”

Bastian garnered further favorable reviews by committing Delta to give $30,000 to each passenger—not just the 20 or so who were hospitalized. Delta also covered medical bills in the days following the accident. Letters written on Bastian’s letterhead and individually signed by the CEO went to each passenger’s home.

Fallout from the crash is far from over: Several passengers have already filed suit against Delta. Thomas Demetrio, an attorney who represents plaintiffs in airline liability cases, believes more litigation is coming. Still, he awards Delta high marks for its response. “The payment was very good PR, because it was phrased as helping people with their immediate needs,” he says, adding that it’s likely to create goodwill. “It’s rare for an airline to step up to the plate this early.”

In his role as crash crisis manager, Bastian was taking an original flight path, and it’s hardly the first time he’s done so. Indeed, for 15 years, including Bastian’s nine as CEO, Delta has often charted a course in the opposite direction from its rivals. When other airlines reckoned that low prices were the biggest lure for customers, Delta bet that fliers would pay a premium for a superior experience. When the pandemic pressured the industry to slash capital investments, Delta kept building.

Today, that contrarianism has made Delta the largest U.S. air carrier by revenue, and the most profitable—while earning the kind of customer loyalty that can help it weather catastrophes like the Toronto crash. Its place atop the podium represents a crowning achievement for Bastian, who has led Delta with a rare blend of salesmanship, showmanship, and an accountant’s mastery of return on capital—and who has helped the airline build strong employee-management relations in an industry where those ties are often strained.

Even competitors respect Delta’s strategic acumen. “I admire Delta,” Frontier Airlines chairman Bill Franke tells Fortune. “They’ve done a terrific job on reliability and meeting the needs of the business traveler.” The former CEO of another major airline, who asked for anonymity in order to speak candidly, also credits Delta for its big bet on upscale service. “I do believe they do a better job catering to premium travelers than American and United,” declares this person. For Raymond James analyst Savi Syth the best measure of Bastian’s foresight is that United Airlines is embracing Delta’s focus on affluent travelers: “The highest form of flattery is that United’s copying them.”

The question is how long the good times will last. It’s far from certain that travelers’ shift from price sensitivity to comfort is permanent: A recession could test their willingness to splurge. Bastian himself waved a warning flag in March, after Delta uncorked a jarring negative surprise—revising its revenue guidance downward for Q1 of 2025 by a sobering $500 million. (Delta’s stock sank around 10% on the news.) Bastian attributed the drop to a “stall in consumer and business confidence” owing to new “uncertainty” over policy in Washington, D.C., and the course of the economy.

Even so, Bastian insisted that demand hadn’t weakened for Delta’s signature premium travel—just the opposite, as the numbers showed. And even if this turbulence continues, the CEO has made one thing clear: He intends to remain at the controls.

Seated in his office in Atlanta, in a quaint, cottage-like brick office building once occupied by Delta founder C.E. Woolman, Bastian walks Fortune through the playbook that earned Delta its lead. His face framed in oversize rectangular tortoiseshell glasses, the CEO is sporting his signature uniform of a blue suit, an open-collared white shirt accented by black buttons, and blue Berluti dress shoes with white soles.

On-time reliability and smart investments in airports and amenities have helped build Delta’s dominance, as have good labor relations. (Delta ranks No. 15 this year on Fortune’s list of the 100 Best Companies to Work For.) But the pursuit of the premium flier is the story Bastian is most eager to tell.

It’s a story interrupted and accentuated by COVID. Bastian grew up in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., the eldest of nine kids. His dad, who died young, was a dentist, and his mom served as his hygienist. “My mom was my mentor and greatest supporter,” Bastian says. “She raised most of the family herself.” Just before COVID struck in force, Ed’s hero died at age 84. “My world stopped,” he recalls. “I gave myself 10 days to pity myself. [But] when COVID came, it was the most important time in 100 years to sit in that seat. You develop that muscle, that leadership style.” Bastian would tap those reserves of strength to make daring moves while the industry retrenched.

Bastian had been Delta’s CFO in 2007, when it emerged from bankruptcy. “We knew we’d never be successful just aiming for the lowest cost,” he recalls. “That was a race to the bottom. We needed to break out of the commodity syndrome.”

Back then, Delta was selling only 15% of its first-class seats, giving the rest away in upgrades—standard industry practice at the time. Front-of-cabin fares cost 10 times an economy ticket. Delta’s innovation was to segment its planes into more fare classes, banking that overall revenue would increase. “We were the first to radically lower the cost of first class,” Bastian says. “Then in 2012, we were the first to introduce basic economy so that we served bargain hunters.” Two more premium classes followed.

Delta reaped steady gains from the strategy through the 2010s. (Bastian became CEO in 2016.) But the aftermath of COVID turned the market more than ever in Delta’s direction. “People who usually went first-class for business now only flew leisure,” Bastian notes, “and went first-class on vacations.” Cooped-up families craved travel, while baby boomers flush with stock market and home-appreciation wealth were ready to splurge. Concludes Bastian, “The premium approach no one else thought would work 15 years ago came fully into its own.”

In addition, Delta exploited the pandemic travel lull to accelerate construction and renovation of terminals across the country. With the airports mostly closed, Delta could complete those megaprojects far ahead of schedule. The airline saved billions, as labor costs and interest rates were low; passengers returning from lockdowns were greeted with gleaming new facilities.

Bastian has been compensated well for Delta’s success. His base pay, about $950,000 a year, hasn’t changed since 2019. But stock awards and bonuses have been more rewarding: In 2023, the most recent year for which figures are available, the CEO received $34 million in total compensation, according to Delta’s proxy filings; that included $9.6 million in bonuses, $6 million in other incentives, and $17 million in restricted stock units, where the eventual payout will depend on Delta’s earnings and stock performance for the three-year period ending this December.

As rich as that sounds, it wasn’t an outlier in Delta’s industry: Robert Isom of American Airlines got $31.4 million in total compensation in 2023, while Scott Kirby of United received $16.5 million. But it was a relatively big haul compared to Bastian’s compensation in earlier years, and much of it was identified by Delta’s board as a “one-time enhanced award”—for leading the airline through COVID.

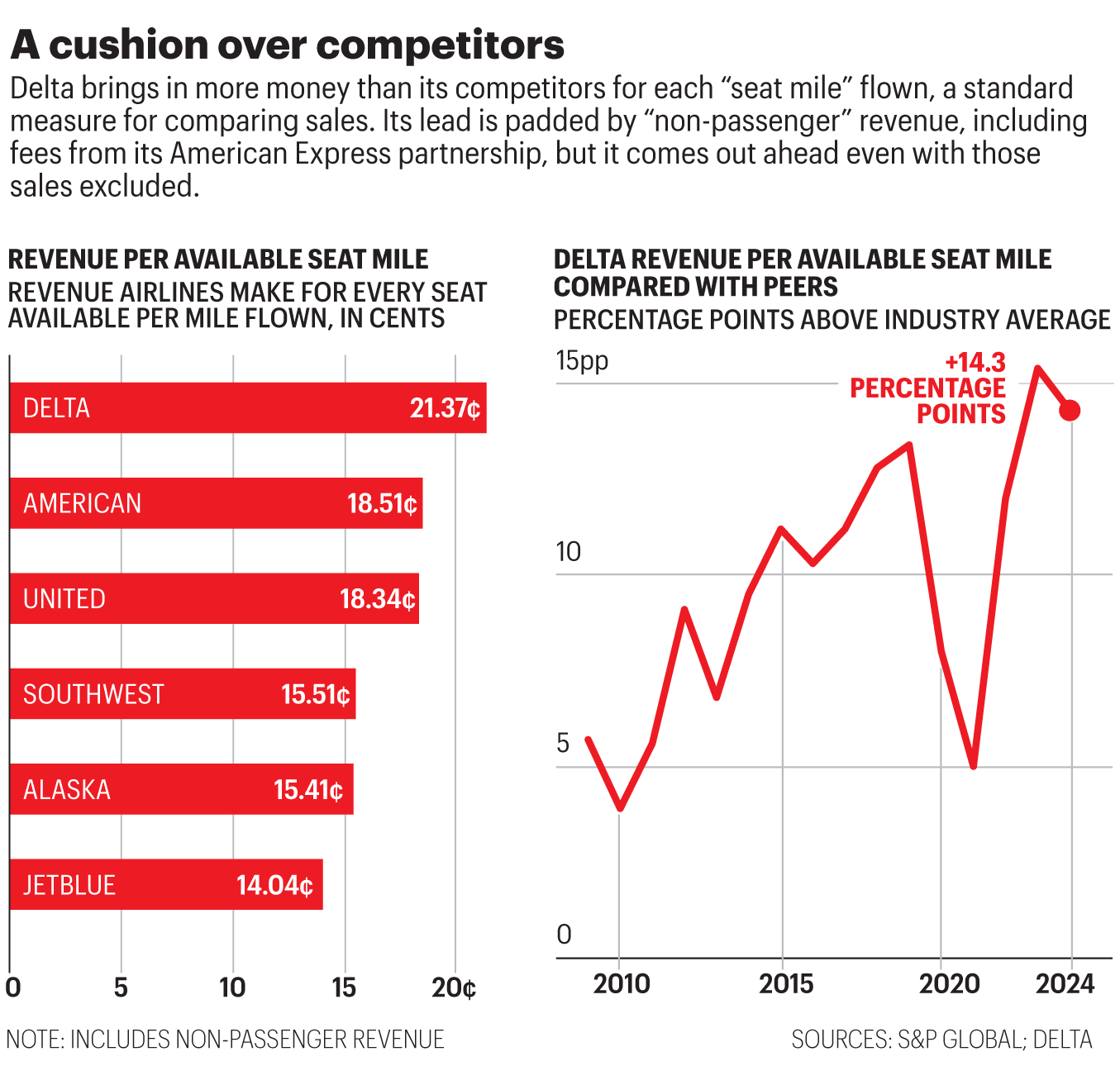

Bastian’s premium playbook has yielded one very measurable premium: Delta collects more revenue per flier than other carriers do on the same or similar routes. In 2024, that cushion averaged 14.3% across all flights worldwide. Last year, Delta collected 21.37 cents in total revenue for each seat flown one mile. That was 15% and 17% better than American and United, respectively; 38% better than both Alaska and Southwest Airlines; and 52% above JetBlue, according to the airlines’ earnings reports.

“We knew we’d never be successful just aiming for the lowest cost. That was a race to the bottom.”

Ed Bastian, CEO, Delta Air Lines

Delta doesn’t have more premium seats than its principal competitors; it just gets more dollars for them on average. “The question,” explains Glen Hauenstein, Delta’s president, “is who gets the highest-quality customers who tend to come in at the end of the booking curve,” meaning the days and hours closest to takeoff.

Delta, like all airlines, uses “revenue management” algorithms to hold back premium seats for walk-up customers willing to pay top fares: Think deal-closing business travelers. Delta captures much more of that traffic than its rivals, says Hauenstein, and that rush accounts for most of Delta’s 14% advantage. Adds Joe Esposito, head of network planning, “We’ll know from past trends how many people, say, for the JFK-LAX route, will want to go that day. Of course, we get higher fares for those seats.”

An airline can capture such business only if it’s ultrareliable. That’s why the fundamental factor in Delta’s success is on-time performance. In 2024, nearly 84% of its flights arrived on schedule, according to aviation analytics site Cirium, putting Delta in first place in North America for the seventh year running. Second-ranked United achieved 80.9%, and no other U.S. carrier breached 80%.

Delta rang that bell despite one of the greatest failures of Bastian’s tenure. In July, a faulty signal from software operated by cybersecurity giant CrowdStrike snarled the computers that control Delta’s reservation systems. The outage hammered other airlines as well, but Delta suffered a particularly sustained hit. Over a week, it canceled 7,000 flights, disrupting travel for 1.3 million people.

Bastian got loads of criticism, including from furious customers who found themselves sleeping on airport floors while the CEO flew to Paris for a Delta board meeting and the Summer Olympics. (Delta was a sponsor of Team USA.) Still, the meltdown only briefly marred Delta’s operational reputation. “Their on-time record is a huge advantage,” says Peter Vlitas, who heads airline partner relations for Internova Travel Group, the parent of a global corporate travel firm.

Delta also gets unmatched lift from its flagship airport, Hartsfield-Jackson International in Atlanta. Huge “hub” airports are typically airlines’ biggest profit machines, for a simple reason. The “cost per enplanement” for each passenger—the amount paid by the airlines to the airports for terminal rentals, landing fees, fuel-facility charges, and other ground expenses—gets lower the more gates an airline controls at a given airport.

At Atlanta, Delta captures the largest economies of scale of any airline, because Hartsfield-Jackson is the world’s busiest airport. Delta handles over 45 million passengers a year there, at some 150 gates. “In any given day, 40% of Delta’s flights touch Atlanta,” says Delta CFO Dan Janki. “The highest competitor is in the low 30s.” Delta doesn’t disclose its margins at Hartsfield, but according to Brian Sumers, editor of The Airline Observer, “the conventional wisdom holds that Atlanta is the most profitable hub in the world.”

Delta earnings also get a boost from the most lucrative credit card partnership in the business. Bastian has said that spending on Amex Delta co-branded cards approaches a staggering 1% of U.S. GDP, or nearly $300 billion a year. American Express then pays Delta to purchase miles that card users can redeem for tickets and upgrades. In 2024, Delta pocketed $7.4 billion from Amex—equivalent to 13% of Delta’s revenues, and an 80% increase over 2019. Delta doesn’t disclose margins on that sum, but industry sources estimate it’s over 30%.

Overall, Delta generated $5.19 billion in adjusted, pretax profits in 2024. Delta’s margin on sales of 9.1% led the airline pack. And Bastian sees it climbing this year—despite the carrier’s rough first quarter.

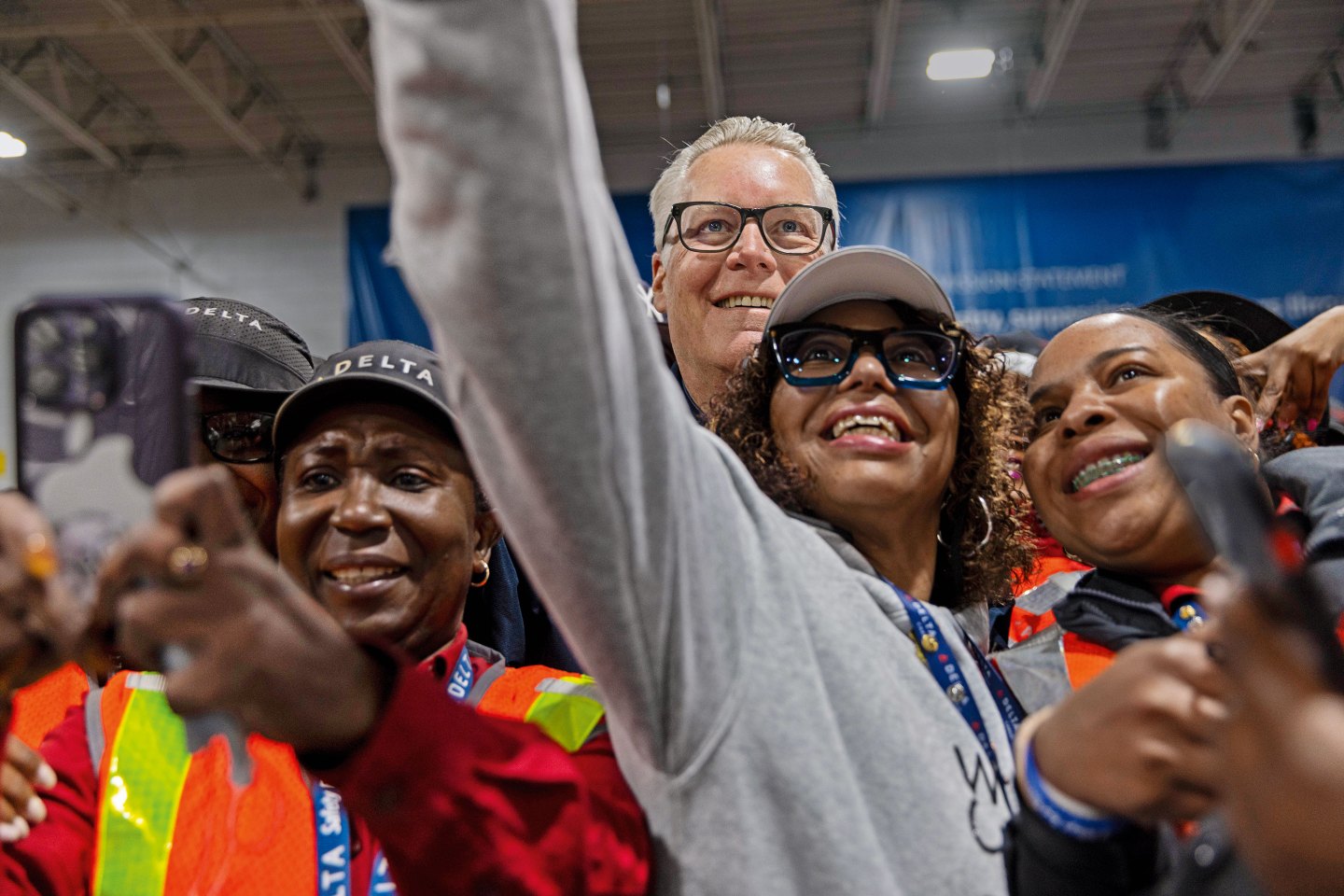

Much of Delta’s premium reputation comes down to customer service. In an industry notorious for conflict between workers and bosses that often spills over into unfriendly or blasé treatment of travelers, Delta has gained a reputation for great labor relations. To see how Bastian and Delta keep the peace, Fortune tagged along with the CEO on Profit Sharing Day.

Measured in both dollars and share of pay, Delta harbors the most generous profit sharing of any major U.S. company. The plan started just as Delta emerged from bankruptcy in 2007, as a deal with its pilots in exchange for deep cuts in compensation. Bastian—then CFO—pledged to flight attendants, gate agents, and the other employees who had also taken big cuts that if Delta thrived, they would benefit via a comparable program. Delta followed through, and the formula remains the same: Employees each year receive 10% of Delta’s first $2.5 billion in adjusted profits and 20% of anything over that threshold. For 2024, the employee share totaled $1.4 billion, amounting to around 10% of base pay.

Delta always dispenses bonus checks on Valentine’s Day, and the partying rages all day at warehouses and break rooms from LaGuardia to LAX. At this year’s bash in Atlanta, Bastian was toastmaster. At a five-story customer call center, balloons filled the air, and money guns carpeted the floors with fake bills. The revelers, phones held high, formed two lines, and Bastian marched down the middle slapping two-handed high fives. “Now that we’re 100, let’s party!” bellowed the boss, who posed one-on-one with agents who’d just gotten checks for $5,000 or more.

All day, Bastian got a rock-star reception from flight attendants, cargo agents, baggage handlers, and other staff. He regularly stopped to shout, “We’re celebrating the best profit sharing in the world for the best employees in the world!” The bandwagon stopped only when iconic Atlanta rapper Big Boi took the stage for a concert on the tarmac.

Delta’s competitors are highly unionized, while at Delta only the 20,000 pilots and a few hundred dispatchers—out of 100,000 employees—are organized. Being union-light doesn’t fully explain Delta’s customer-service-focused culture: Southwest, which also wins high marks for service, is fully unionized. In conversations, however, many employees told Fortune their culture benefits from constant contact with leadership that wouldn’t be possible if a union were making their case.

Delta is certainly a target for organizing. The powerful Association of Flight Attendants–CWA has made three unsuccessful attempts over the past couple of decades and is campaigning for a fourth. “They have a unique anti-union culture,” AFA-CWA chief Sara Nelson says. “They say their flight attendants are the best paid, but their cash pay and benefits are well below the other airlines.” (Delta says that its profit sharing puts total pay above the industry average, a contention Nelson disputes.)

Delta has kept unions at bay in part by proactively expanding pay and benefits. It was the first airline to give flight attendants “boarding pay,” additional compensation for the stressful 40 to 50 minutes they spend seating customers for takeoff. Delta has also established a structure through which employees can voice concerns directly to management. The Delta Board Council comprises five reps, one each for management and corporate staff, call-center staff, maintenance workers, flight attendants, and gate and other airport service agents. Each year, one rep occupies a nonvoting seat on Delta’s board.

In a joint interview, council members Alysha Nemeschy and Mallory Brown, who respectively represent in-airport customer service and flight attendants, discussed their experiences. Management had been responsive to requests from the council, they said, including an expansion of free “pass travel” privileges for employees’ friends and payment for hearing aids for all employees.

As for unions, Brown stated, “As long as [management] keep doing the right thing and listening to us, the less need for unionizing we have.” The pair appreciate the fact that the council comprises voices from across the company, and they’re wary of the “fragmentation” that would occur if different unions represented different employee groups. “Having all functions work together is what makes Delta feel like family,” says Brown.

The Valentine’s Day throwdown proved ideal for quizzing attendees about whether Delta would benefit from a union. Most said they like things as they are. “I used to work at Northwest and United, and saw there’s not much a union can stop,” says cargo agent Epic Journey (whose name matches her ebullience). “Delta’s management doesn’t have to be forced to do right.” Says Lorenzo Hall, who transports baggage on “tugs”: “It would be great to see [managers] more in the break room. But no, we wouldn’t benefit from a union.”

That view wasn’t universal. Stated Justin Rush, a lead agent in charge of loading aircraft, “I’ve seen some people that have clean records on the job, and then they’re just gone, so I feel we would benefit from a union to protect people’s jobs. It’s a great company, but they need to invest more in its equipment and its people.”

Equipment took center stage when Delta celebrated its 100th anniversary on Jan. 7. The party was the first corporate event ever held in the Las Vegas Sphere, a giant, otherworldly-looking orb ringed inside by the largest LED screen in the world. (Delta took over the venue from the act in residence, the Eagles.) For 90 minutes, Bastian played MC in an extravaganza designed to showcase new in-cabin goodies.

Up popped Tom Brady, whom Bastian has hired to share leadership secrets at management meetings. The seven-time Super Bowl champ, attired in a suit the color of vanilla ice cream, talked about Well-Traveled, an exclusive in-flight show he’ll star in on Delta’s seat-back screens. Bastian singled out DraftKings CEO Jason Robins in the audience, then announced that onboard sweepstakes games were coming to the airline. Alongside a YouTube exec, Bastian revealed that the streaming service would soon be available on Delta sans ads. On and on the parade went, as the Sphere’s screens projected enormous images of things to come. Standing before them, Bastian appeared like a tiny Gulliver contemplating a wondrous universe of flight.

In real life, Delta has already widened its tech edge. It was the first network carrier to offer free Wi-Fi, which SkyMiles members can now access on most domestic flights. Delta’s 165,000 seat-back screens lead the industry by far. Delta is also switching to “software-enhanced” screens that recognize customers who use the Fly Delta app—enabling fliers to restart a movie where they left off on their last flight, for example. On new aircraft, Delta will offer screens that can order Ubers for you and make restaurant reservations based on your taste in cuisine.

As for lounges, Delta now boasts some of the world’s plushest. Its Delta One Lounge at JFK, opened in mid-2024, offers a spa where customers can get “jet-lag reviver” scalp-and-temple massages, or shower in huge bathrooms befitting a five-star hotel. The Boston Delta One opened last fall, and branches in Seattle and Salt Lake City are due in mid-2025.

Delta may need such perks to keep its premium gusher flowing. Its industry-leading profit margin of 9.1% actually lags its performance from 2015–19, when pretax margins reached as high as 15.8%. Bastian says Delta is en route back to those peaks. It’s not there yet, he says, because of expenses it shouldered in its post-COVID expansion, including hiring and training 40,000 people to keep service at high levels.

Delta carries the industry’s highest costs, so to grow profits, it must continue collecting much higher average fares per seat flown than competitors. The potential problem: As Delta sells more front-of-cabin seats, it has less room to offer upgrades to frequent fliers. And that tension has sparked unrest among the more than 120 million members of SkyMiles.

In 2023, Delta misfired by sharply hiking the expenditures needed to reach different status tiers. Delta moved the benchmarks because it was getting far more upscale passengers—and handing out more upgrades—than the program was designed to handle. As loyalists swamped the internet with outrage, the CEO scaled back the increases. But the annual spending requirement still jumped. The cutoff for Diamond status, for example, rose from $15,000 in 2022 to the current $28,000. The number of SkyMiles needed for upgrades and free tickets also climbed steeply.

SkyMilers say the plans are now delivering much less than in the past, and many of them are pissed off. “Last year, I was getting 55% free upgrades,” says Clint Henderson, managing editor of industry newsletter The Points Guy and a Delta Diamond member. “Now it’s maybe half that. A lot of people are reassessing whether to stay on the hamster wheel. Maybe you should take the flight that’s cheapest and fastest.”

For now, most longtime fans are sticking with Delta; indeed, the airline attracted an additional 1 million Delta Amex cardholders last year. But if members view the power of their SkyMiles and status as diminishing, the question is whether Delta’s leads in reliability, service, and amenities will enable it to maintain its big fare advantage.

Delta’s Q1 2025 revision showed how vulnerable this balance can be. As Bastian explained, the airline’s famed revenue management system didn’t come through. Delta held back a high percentage of premium seats, expecting tons of high-fare walk-up business—which didn’t arrive. That left the airline with an overhang of inventory that it wound up selling at much lower prices than anticipated.

Meanwhile, United and American are pivoting to target affluent customers. And low-cost carriers could grab market share if the economy slackens. “Bastian’s done a remarkable job … but Delta’s costs and those of the legacies are high,” says Franke, the Frontier chairman. “The most important thing is to leave and arrive on time, and the next most important thing is price.” Delta is winning on only one of those fronts.

Ed Bastian will turn 68 in June. He’s served as Delta’s CEO for almost nine years, the longest reign among chiefs of major U.S. airlines. No CEO this writer has met appears to be less stressed or having more fun than Bastian; he clearly loves the job and the adulation that comes with doing it well.

Bastian has never publicly discussed succession in any detail. At his office in Atlanta, he batted away a question about his departure, stating, “I have a number of years to go. This is not a swan song.” But when I asked, “Has the board named a CEO if something should happen to you?” Bastian said yes. I followed with, “Is it an internal person?” The boss said yes again. He’d never before disclosed either of these crucial arrangements.

Bastian’s not divulging the heir apparent’s name. Sources with whom I spoke say that Delta has several strong candidates, though no obvious front-runners. One contender may be Janki, the CFO, whom Delta hired in 2021 from his post as CEO of GE’s power business. Others include Erik Snell, who holds the top position in customer service; Peter Carter, head of external affairs; and Allison Ausband, Delta’s EVP and chief people officer.

If Bastian does retire, he won’t lack for things to do. He’s especially thrilled these days about his new membership at Augusta: He’s become crazy about golf, a pastime unavailable to him while managing eight siblings in Poughkeepsie. He regularly takes to the links in Florida with such fellow CEOs as Carrier Global’s Dave Gitlin. Bastian says Gitlin’s an ace but is vague about his own handicap, disclosing only that it’s well into double digits—an uncharacteristically evasive answer from an ardent numbers man.

But for customers and employees alike, right now Ed Bastian is hitting every fairway.

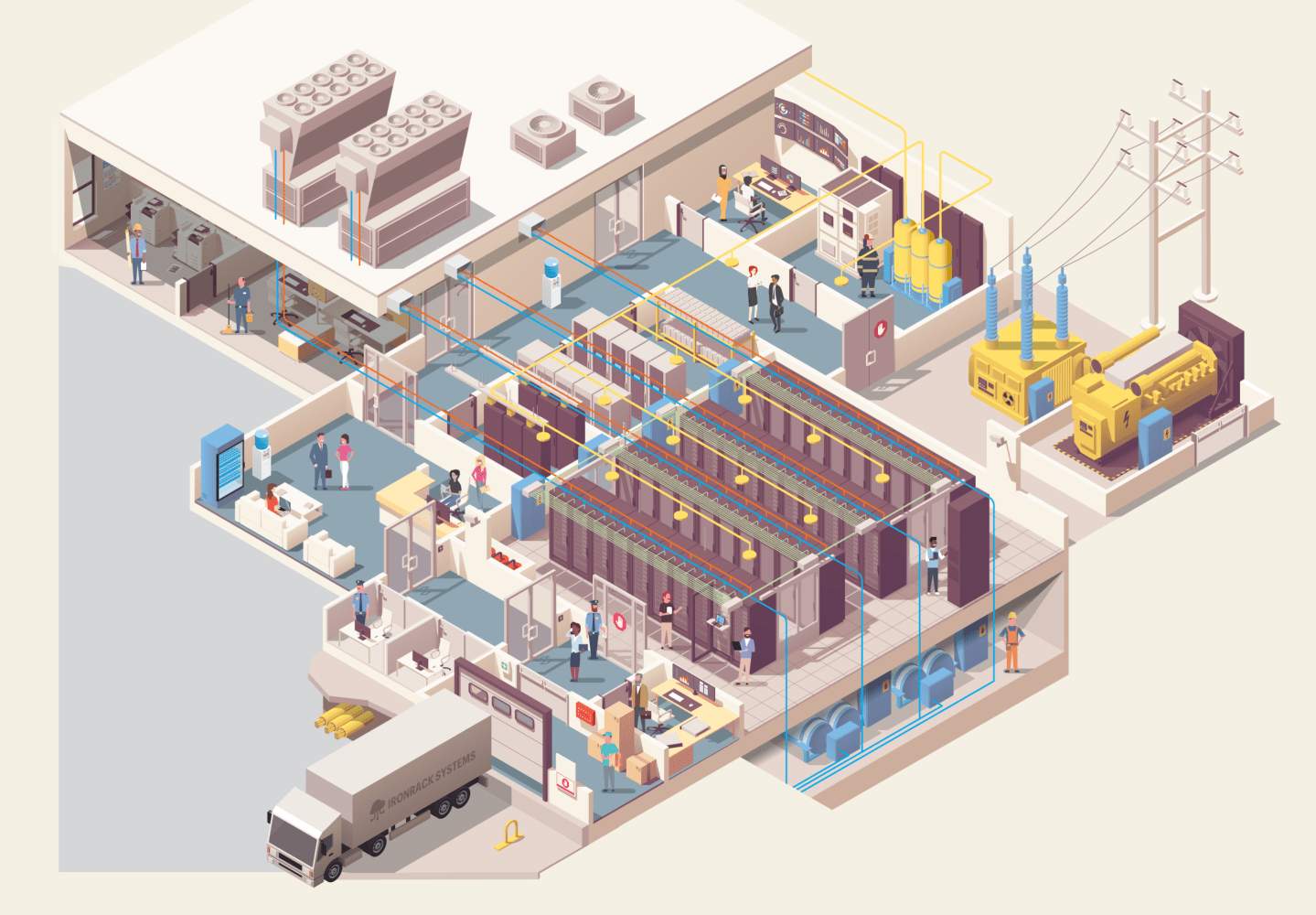

How Delta gets top dollar

Delta was America’s most profitable airline last year, and it generated 14% more revenue per “seat mile” than its competitors—largely by wooing travelers who don’t mind paying a premium for reliability. Here’s how the airline maintains that cushion.

On time, most of the time

Delta’s North American flights arrived on schedule nearly 84% of the time in 2024—putting it in first place for the seventh straight year, which endears it to time-pressed business fliers.

A handy hub

Delta has 73% market share at Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International, the world’s busiest airport. That makes Delta a must-fly carrier for many, while helping boost its profit per passenger.

Keeping staff satisfied

A generous companywide profit-sharing program helps Delta build goodwill among its frontline staff, which in turn correlates with better customer service.

Fresher facilities

During COVID-era travel slowdowns, Delta sped up its investments in new terminals, airport lounges, and in-flight entertainment tech—amenities that lure finicky fliers.

This article originally appeared in the April/May 2025 issue of Fortune with the headline “Profit Pilot.“