If you’ve been conscious lately and haven’t heard of Apple Computer, you’d better have your ears examined. But don’t worry if that name zooming up from the Apple tombstone doesn’t ring a bell. Hambrecht & Quist, which co-managed Apple’s (AAPL) first public offering with the prestigious Wall Street firm of Morgan Stanley, is a San Francisco upstart only 13 years old. In 1980 Merrill Lynch, the industry leader, did 45 times as much underwriting business as Hambrecht & Quist. But when it comes to financing small high-technology companies like Apple, Hambrecht & Quist has a special touch.

The firm is both underwriter and venture capitalist. It has five venture-capital funds, with about $100 million in assets, which it manages primarily for large institutional investors. The oldest one invested in over 100 companies in ten years and returned an average of 29.8% a year, compounded. The second fund, launched two years ago, has returned a breathtaking 59.9% a year. A competitor, Sanford R. Robertson, a partner of San Francisco’s Robertson Colman Stephens & Woodman, remarks: “If you can beat them it’s like winning a game of golf against Arnold Palmer.”

Hambrecht & Quist pours its venture capital into fledgling enterprises, gets seats on the boards, and often takes the companies public. It underwrote 25 equity issues worth more than $400 million this year, its best ever. But its several roles—as investor, director, underwriter—have raised questions about whose interest it serves, its own as investment banker or that of all the shareholders.

The firm’s founders—William R. Hambrecht, 45, and George Quist, 55—are as venturesome as the entrepreneurs they underwrite. The son of a San Francisco milkwagon driver who emigrated from Denmark, Quist played his way through Berkeley and Stanford on football scholarships. He likes to point out that he’s “the only living person” who has been captain of both those arch-rival teams. After college he joined Price Waterhouse as a CPA, later worked for Kaiser Gypsum, and, when he was 26, became president of Mandrel Industries, a money-losing manufacturer of precision instruments. Through mergers and acquisitions he built Mandrel’s annual sales from $600,000 to $20 million and eventually sold out to Ampex, a maker of videotape recorders and data-processing equipment. In 1961 he started Explosive Technology, which makes devices for missiles, and later sold it to Ducommun Inc. Then he joined Bank of America as president of its venture-capital operation.

Tall, boyish-looking Bill Hambrecht, the son of a Mobil Oil manager, grew up on Long Island, and graduated from Princeton in 1957. He got his first exposure to the world of high technology when he took a job with Security Associates, a Florida investment-banking firm. He sold securities and managed underwritings for small technology companies even though, he confesses, “science was always my worst subject.” But he caught on, and in 1965, shortly after Francis I. du Pont & Co. acquired the firm, Hambrecht was dispatched to San Francisco to set up a corporate-finance office.

Agreement at the Kona Kai

Collaborating on several West Coast venture-capital deals, Hambrecht and Quist became kindred entrepreneurial spirits. One evening in 1968, after spending the day together studying the investment possibilities of a budding San Diego outfit, they stopped for a drink at the Kona Kai Club. It didn’t take too many Scotches before Hambrecht started complaining to his buddy: du Pont wanted him back in New York, but he was having fun underwriting little companies. “I really wanted to be responsive to smaller technical companies,” he says. “But it was difficult to do that in a large New York firm.” After a couple of drinks and a couple of bottles of wine, they decided to strike out on their own.

With Silicon Valley nearby, it takes just picoseconds to pursue a hot tip.

Over black coffee the next morning, Quist says, the idea “still sounded good.” On the plane back to San Francisco they hastily drew up a business plan. In those heady times, backers weren’t hard to find. They raised $1 million that very day from Prentice Hale, then chairman of Carter Hawley Hale department stores, and Henry McMicking, a major investor in Ampex, among others who became limited partners.

Hambrecht and Quist invested most of that $1 million in new ventures. To pay the rent, they cajoled Smith Barney, Lehman Bros., and other big firms to hand over underwriting jobs they considered too small or risky to handle. The “rejects” Hambrecht & Quist took public included Spectra-Physics, Datapoint, and Tymshare—now big names on the Big Board.

When the equity market fizzled in 1974, Hambrecht & Quist underwrote just two issues all year. The limited partners, who by then had invested $4.8 million, got jittery. Liquidating part of their venture-capital portfolio and taking out a $2-million personal loan, Hambrecht and Quist paid back most of the limited partners’ capital. They cut their own salaries in half and closed their New York office. Hambrecht put his 17-room Marin County house up for sale, but there were no takers. “In 1974,” he says, “we used to sleep every other night.”

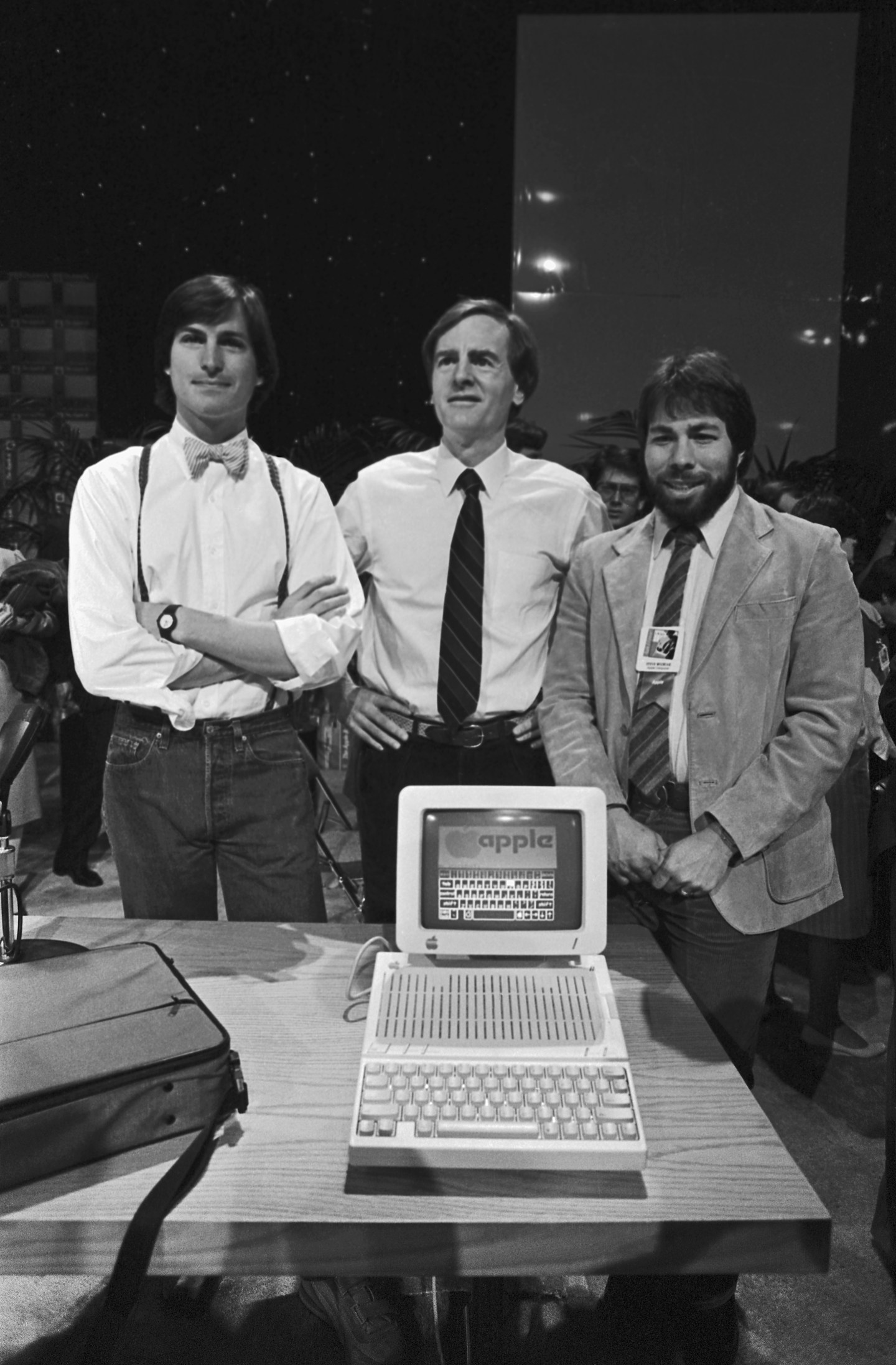

Whom the Apples Fell on

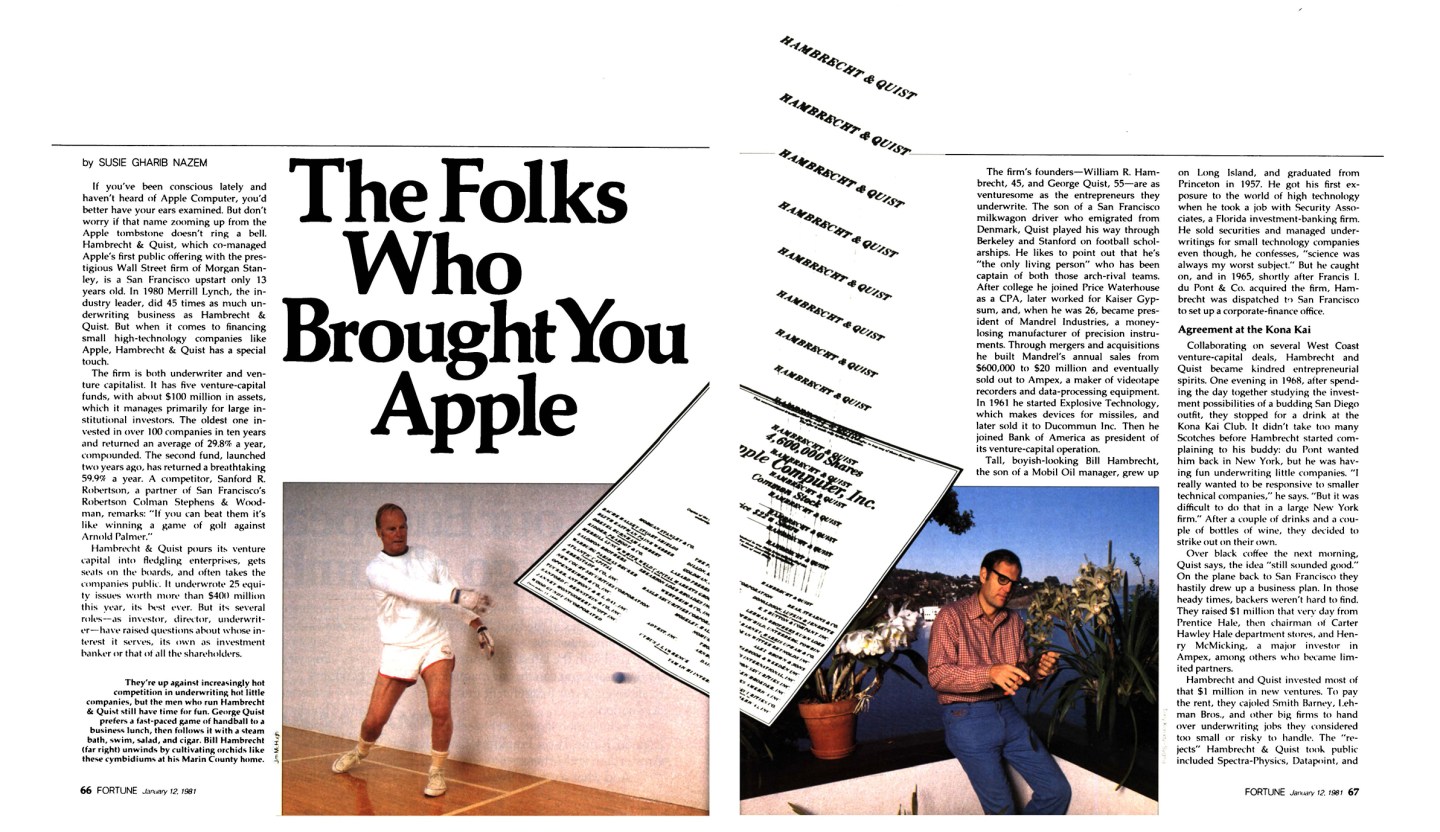

In the 45-mile stretch between San Jose and San Francisco called Silicon Valley lives a computer-age version of the American dream. It turned to reality recently when Apple Computer went public at $22 a share. Venture capitalist Arthur Rock, who invested $57,600 in the company three years ago, ended up with stock worth $14 million; Teledyne Chairman Henry Singleton’s investment of $320,800 blossomed into $26 million. Impressive enough, but nothing like what happened to Apple’s young founders, Steven P. Jobs, 25, and Stephen G. Wozniak, 29.

Graduates of Santa Clara’s Homestead High School, Jobs and Wozniak dropped out of college. The self-taught computer whizzes went to work for local electronics companies. The two began collaborating five years ago at the Home Brew Computer Club in Palo Alto. They designed their first machine in Jobs’s bedroom, built it in his parents’ garage, and showed it to a local computer-store owner, who promptly ordered 25. Demand for the “personal” computer, mainly from hobbyists, soon outstripped the young men’s ability to produce, so they began looking for help.

Enter A. C. Markkula Jr., 38, who had been marketing manager at Intel, the fast-growing producer of integrated circuits. “Mike” Markkula was soon convinced that the two Steves, as they are known at Apple, were on to something big. He put up $91,000, secured a line of credit, and later raised some $600,000 from venture capitalists. Markkula became chairman of the company in May 1977, and Michael Scott, 37, signed on as president a month later, taking a 50% pay cut from his job as a director of manufacturing at National Semiconductor.

You don’t need an Apple computer to tell you that at least four new multimillionaires are now roaming the Silicon Valley. The four men own 40% of the company, which earned $11.7 million on sales of $117 million last year. At the public-offering price, Scott’s shares were worth $62 million, Wozniak’s $88 million, Markkula’s $154 million, and Jobs’s $165 million. Wozniak spread the wealth among his relatives. His parents and siblings own nearly $3 million in Apple stock. His wife, Alice, owns $27 million. They are separated.

—Grant F. Winthrop

Something out of the Depression

From those days they learned to stay small and keep overhead down. Hambrecht & Quist’s scruffy quarters look like government offices in the Depression. No Eames chairs, no Kirman carpets, no Touch-Tone telephones. The staff totals 90, with only three professionals in the syndicate department and five in corporate finance.

Employees are treated more like entrepreneurs than hired hands. Institutional salesmen have to pay half their expenses, including secretaries’ salaries, telephone calls, and airplane tickets. Analysts not only write research reports but also help put together prospectuses and study venture-capital deals. They earn less than the industry average in base salary, but can cash in on hefty bonuses depending on their contribution to profits. The annual paycheck for an analyst can run as high as $300,000.

For more on Apple, watch this Fortune video:

Only a few investment-banking firms have venture-capital funds—Blyth Eastman Paine Webber, the Rothschild family’s New Court Securities, Donaldson Lufkin & Jenrette—and none of the others plays its hand as aggressively as Hambrecht & Quist. Of its venture-capital funds three are exclusively for Europeans, partly for tax reasons. The firm invests $150,000 to $2 million in a young company’s second round of financing; it rarely puts up seed capital. It takes shares as small as 0.2% (Cetus Scientific Laboratories, a gene-splicing outfit) and up to 50% (Margaux Controls, a manufacturer of energy-saving devices). The funds contribute 70% of the investment and Hambrecht & Quist’s partners put up the rest. Then one of the senior partners goes on the board. Between them Hambrecht and Quist serve as directors of 23 companies.

Hambrecht & Quist isn’t free to bully.

The partners prod the management on strategic planning, product development, and finance, and are on call around the clock to help chief executives solve their problems. So when the time comes to go public, Hambrecht & Quist is well positioned to get the underwriting job. The boardroom also becomes a listening post to learn of other opportunities. Last month Hambrecht & Quist agreed to invest $1.4 million in VLSI Technology, a semiconductor outfit in Los Gatos, California, after getting a tip from David Evans, chief executive of Evans & Sutherland, a designer of computer-graphics systems of which Hambrecht is a director. With Silicon Valley in its backyard, the firm can follow a lead practically within picoseconds. “I always ask a company who else is doing something interesting in the field,” says Hambrecht. “It’s important to invest in a company that has its competitors’ and suppliers’ respect—not in one that Wall Street thinks is hot.”

Three years ago Hambrecht & Quist’s research department wanted to buy a word-processing machine and, after listening to sales pitches from IBM, Xerox, and Wang, settled on an obscure outfit from Boulder called NBI. Once Hambrecht bought the machine he called up NBI President Thomas Kavanagh and asked if he needed money. He did, and Hambrecht & Quist snapped up an 8% stake in the company at $4.20 a share. Last year it took NBI public at $20. The shares are now trading around $65.

How big a man thinks

In finding winners, Hambrecht & Quist looks for a unique technology, good products, a strong balance sheet, and common-sense-oriented managers. The balance sheet is more critical than the income statement. “You can show beautiful profits,” Hambrecht says, “by burying inventories.” Competent managers, he adds, pull the whole thing together: “You can tell by the way a guy hires how big he thinks. The guy who hires weak people is the one youhave to worry about.” What finally sold Hambrecht on NBI was that its top executives came from places like Storage Technology, Xerox, and Data General.

Hambrecht & Quist has been fooled at least a dozen times in its more than 100 venture-capital investments. Last year it put $1 million into Logisticon, a Sunnyvale, California, manufacturer of automated systems for warehouses. “The problem was that the president was a perennial optimist,” says Hambrecht. “He was always betting the company would have a big order and so he got stuck with a lot of inventory.” Last summer Hambrecht & Quist successfully urged the board to change management. Hambrecht says that if he had spent more time with the company, he could have avoided the problem. Now he reports Logisticon is “starting to approach profitability.”

When the firm gets stuck with a loser, it may call in its corporate doctor, Quentin T Wiles. A 61-year-old former executive of TRW, “Q. T.” Wiles makes house calls. He moves into the company, takes over as chief executive, and stops the bleeding. His fourth and most recent patient is Granger Associates, a Santa Clara manufacturer of telephone systems for Third World countries. Granger ran into trouble when its newly installed telephone system in Iran was confiscated by the revolutionary government without restitution. Called in when the company reported a $3-million loss last year, Wiles has put three profitable quarters back to back.

As its business picked up with the market for small stocks over the last three years, Hambrecht & Quist invited Wiles and other investors to become limited partners. For the most part, the firm’s 13 limited partners are high-powered venture capitalists on the West Coast. Each has put $50,000 to $150,000 into the firm, and they can join Hambrecht & Quist’s general partners in venture-capital deals. The limited partners also bring in business. One’of them, Thomas J. Perkins, a member of the San Francisco venture-capital firm of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, introduced Genentech to Hambrecht & Quist, which took the gene-splicing company public in October.

“You want people to feel they invested in a winner.”

A lot of investment bankers criticize the close connection between Hambrecht & Quist’s venture-capital and investment-banking operations. Declares John Castle, president of Donaldson Lufkin & Jenrette: “If Hambrecht & Quist puts its money in a venture, you can bet it will end up being the underwriter too.” He calls this “a shotgun approach” and “investment-banking exploitation.” Those are strong words considering that investment bankers have been directors of large companies for years. Felix Rohatyn of Lazard Frères sits on the ITT board and Lehman’s Peter Peterson on RCA’s; in each case the firm represented on the board handles investment-banking business for the company.

Critics insist there’s a difference with Hambrecht & Quist. With 10% ownership of a company, the firm may have considerable clout with inventor-managers who are unsophisticated about finance. If Hambrecht & Quist were eager for more underwriting business, critics argue, it could pressure a company into going public even if the time weren’t right. In bringing out an issue, it could underprice the shares, making them easy to sell and currying favor with institutional buyers at the expense of its clients.

The potential for wrongdoing clearly exists, but critics are hard-pressed to cite specific instances. Hambrecht & Quist may have an influential director on the board, but it isn’t free to bully. Nowadays, the boards of high-tech companies tend to be sprinkled with several venture capitalists savvy about finance. With their own investments at stake, they are sure to oppose any action detrimental to the company.

“I want the underwriting, but …”

Hambrecht & Quist has a reputation for standing by entrepreneurs in hard times even when doing so isn’t to the firm’s short-term advantage. Modular Computer of Fort Lauderdale was on the verge of bankruptcy two years ago. “Certainly Bill [Hambrecht] stood to gain if the company was sold,” says ModComp Chairman Alexander W. Giles, “but he said it would be a shame to sell and never once went against management on any issue.” Defending his own position, Hambrecht says: “If you’ve got your own money up, you’re on the board to protect your investment. Sure I want to do the underwriting, but not at the expense of the shareholders.”

Controversy also surrounds the pricing of new issues. Hambrecht says his rule of thumb is to set the price high enough to raise the capital needed but low enough so that in a few weeks, after immediate speculative trading has abated, the stock will have appreciated 10% to 20%. “When you’re selling stock to the public for the first time,” he says, “you want people to feel that they invested in a winner.” Alfred “Bud” Coyle of Blyth Eastman Paine Webber agrees: “The worst thing is to price a new issue too high and then let it fall. You want happy customers.”

The trouble with corporate nestlings is they can fly away.

An issuing company might logically argue that it would like to capture some of that extra 10% to 20% for itself. And if there’s a bigger run-up, the question is whether the stock was badly underpriced. When Blyth and Hambrecht & Quist brought out Genentech, they set the price at $35 a share and it hit a high of $89 the first day; it has since settled back to the high 30s. The price for Genentech, a company without product or profit—and unlikely to have either for years—was based on a guess of what the market would bear.

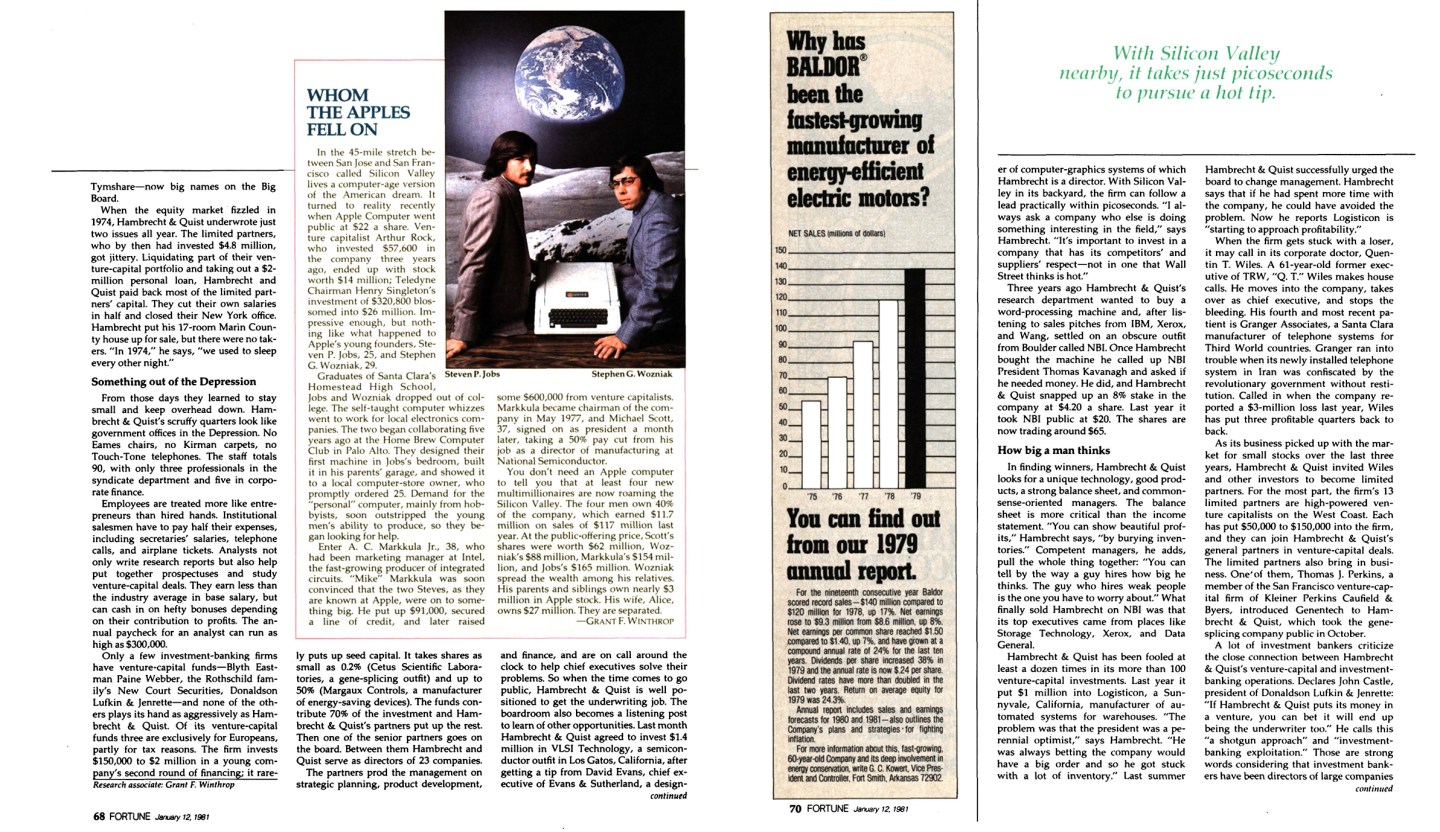

A $1.2-billion Apple

Morgan Stanley and Hambrecht & Quist priced Apple at $22. The price ran up to $29 during the first day of trading, a 30% gain. In calculating the price, Hambrecht & Quist compared Apple with nine somewhat similar companies, including Magnuson Computer, Tandem Computer, Rolm, and Paradyne. These companies were selling at an average of about 18 times anticipated 1981 earnings. But the underwriters figured that Apple’s spectacular growth rate—earnings went up 700% in the last three years—and a faddish enthusiasm for the stock made the company worth a lot more, perhaps 35 to 45 times anticipated earnings.

The sale placed the total market value of Apple, a company that earned $11.7 million in the fiscal year that ended last September, at $1.2 billion. By comparison, St. Regis Paper, which earned $158.5 million last year, has a market value of $1.1 billion. At a stock price of $22, Apple’s earnings would have to more than double this fiscal year, to 55 cents a share, for its multiple to be as low as 40. Massachusetts refused to allow the issue to be sold there, on the ground that it was overpriced; Apple wasn’t offered in 25 other states where laws are stringent.

After the go-go Sixties, the big Wall Street firms lost interest in underwriting new issues. Although the spread, or margins, is high—typically 7.5% of the value of the offering vs. 4% for a large offering of an established corporation—the dollars earned pale by comparison. But now that investors are again infatuated with high-technology issues, Hambrecht & Quist has lots of competitors to contend with, including such heavy hitters as Shearson, Kidder Peabody, Blyth Eastman Paine Webber, and Morgan Stanley. “If you don’t get associated with these [high-technology] companies,” says Robert Baldwin, president of Morgan Stanley, “you’ll miss out on the winners of the future.” Morgan Stanley has targeted 20 technology companies it wants as clients; Apple is the first.

“We got outsold”

For a small, specialized investment banker, the trouble with nurturing corporate nestlings is that they can grow up and fly away. As Datapoint matured, it left Hambrecht & Quist for Kidder Peabody. Four-Phase, a leading producer of video-display computer systems, was picked up by Lehman Bros. Hambrecht, who has been content to share initial underwritings with big Wall Street houses, has discovered that friendly co-managers can become fierce rivals when competing for new clients.

Heightened competition took its toll two months ago, when Network Systems, a Minneapolis-based manufacturer of data-communications equipment, decided to go public. Hambrecht & Quist thought itself certain to get the business. It had sunk $567,000 in venture capital into the company and owned about 3% of the stock. But the job was awarded to Shearson, San Francisco’s Montgomery Securities, and Dain Bosworth of Minneapolis—the first time Hambrecht & Quist had ever lost an initial underwriting for one of its venture offspring. “We got outsold,” Hambrecht admits. “The competition convinced them we were too busy. Maybe they were right.”

Hambrecht & Quist may have been hurt by its “stay lean” mentality. An investment banker who has co-managed offerings with the firm complains: “When we’re drafting a prospectus, there’s a new person every day from Hambrecht & Quist who doesn’t know what was done the day before.” Many potential clients see the firm as depending on a single partner. Quist, the administrator, is not as active as Hambrecht in making deals or drumming up business. Clients gravitate to Hambrecht, the imaginative intellect, a man of energy and drive who is willing to live out of a suitcase four days a week in search of deals.

This year, Hambrecht and Quist sought to broaden the firm’s base by diluting their 30% interests and creating three additional managing partners. Each of the five now owns 12%. Hambrecht thinks the firm needs to add at least 12 to its staff of about 30 professionals just to handle current business. Tops on the list is finding a senior corporate-finance executive to handle business on the East Coast. (“I don’t want to go on a board east of Denver,” says Hambrecht. “Traveling kills time.”)

Nor will Hambrecht & Quist be content to let clients keep outgrowing its services. To hold onto them, it wants to add to its venture-capital and equity-underwriting operations the ability to handle Eurodollar offerings, project financings, bond underwritings, and mergers and acquisitions. Hambrecht would like to do all this without abandoning the firm’s high-technology niche. “I want to be the best risk-type investment-banking firm in the business,” he says. “I’d like to see us end up as a major like Lazard Frères—smart people with a specialty.”

One outsider calls that “self-delusion.” Only time will tell whether Hambrecht & Quist can cultivate an orchard full of Apples, and keep Wall Street from picking them.

Research associate: Grant F. Winthrop

A version of this article was originally published in the January 12, 1981 issue of Fortune.