Global trade’s new playbook: 3 lessons for winning in a world transformed

3M has a big respirator factory in Shanghai. But when the St. Paul–based conglomerate, which ranks No. 382 on this year’s Global 500 list, needed to make more masks as the COVID-19 pandemic mushroomed in May 2020, it didn’t just turn to China. It turned to Aberdeen, S.D. With most hospitals reporting they were operating under “crisis standards of care” because of PPE shortages, 3M quickly added two new wings to its respirator plant there. Within months it was churning out millions more N95s—thousands of miles closer than Shanghai to where they were needed.

Like everything and everyone that has gone through the pandemic, the global economy has been changed in lasting ways, and Fortune’s new Global 500 directory of the world’s biggest companies shows how. Despite dire predictions, globalization didn’t die. It evolved. Onshoring, nearshoring, and reshoring have become imperatives for businesses (such as hospitals) whose supply chains snapped in 2020. That trend played to some companies’ strengths; 3M’s rank in the Global 500 jumped seven places this year, for example, and profits rose 18% compared with the previous year. The directory shows how other trends devastated whole industries, if only temporarily. Last year’s Global 500 included six airlines; this year there are none.

The new Global 500 is a picture of a world we’re rapidly leaving behind and also a guide to the new environment taking shape. Here are three lessons it offers for winning in a world transformed:

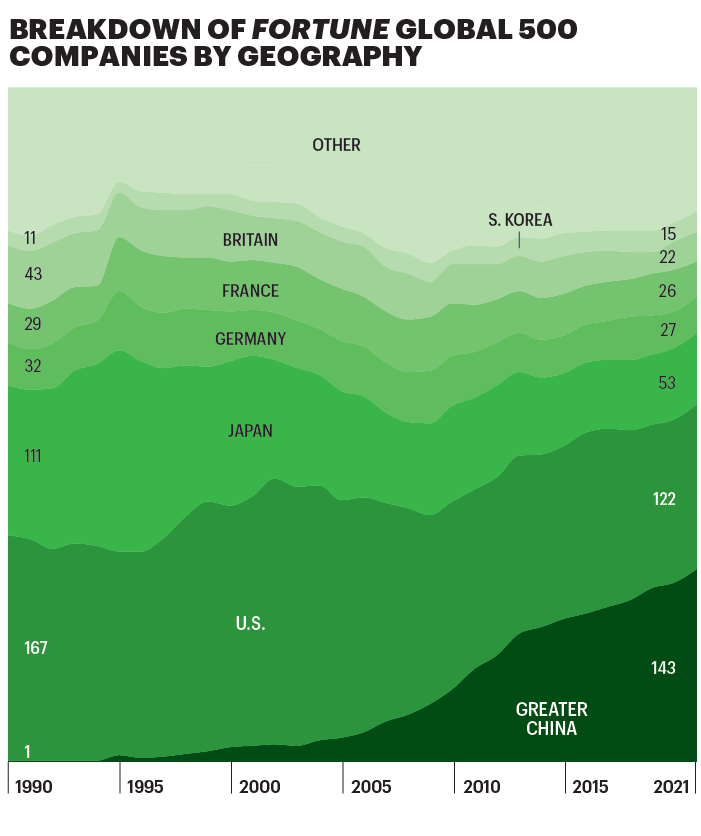

Ride the U.S. and China for growth. Together, the U.S. and China now have more companies in the Global 500 than do the world’s other 193 countries combined. The pandemic separated the two giants further from the rest of the pack, and forecasters expect them to grow much faster this year than the other biggest economies, Europe and Japan. Businesses worldwide are taking note. The U.S. will be the world’s No. 1 destination for overseas investment this year and next, the United Nations predicts, with China right behind. Even companies that don’t want to build factories in the U.S. may want to sell goods and services there. After a year of globally unprecedented economic stimulus in 2020 plus trillions more in federal spending this year, demand is white-hot and unmatched anywhere else.

World GDP got walloped in the pandemic and won’t climb back to pre-COVID forecasts until 2024, says the International Monetary Fund. Companies that focus on the growth drivers, the U.S. and China, can make up lost ground faster.

A supply-chain revolution is underway. The long-standing model of Western companies sourcing goods from China at ultralow costs was under pressure before the pandemic, as tariffs and rising Chinese wages made that nation’s products less of a bargain. Now, after Chinese factories abruptly shut down in the early pandemic just as demand spiked for crucial supplies, a new model is taking shape. The big winners are Asian countries that can underprice China, notably Vietnam, Thailand, and India, plus low-cost neighbors of the U.S. and Western Europe, such as Mexico and Poland.

Major players are leading the move. Foxconn, maker of Apple products at huge factories in China, announced last July that it would invest $1 billion in India. Production of the iPod has moved to Vietnam. Hasbro is shifting toy production from China to Vietnam and India.

Companies have also become more wary of globe-spanning supply chains. Sending a standard shipping container from Asia to the U.S. cost around $3,000 pre-pandemic; in recent months the cost has been $15,000 to $19,000, wrecking the economics of Asia-based production strategies, especially for high-bulk products such as furniture. The larger lesson is that while low costs are great, they aren’t risk-free. For U.S. companies, moving at least some production to Mexico or even the U.S. may be an insurance policy that’s worth the price. Mexico in particular is looking especially attractive. “China surpassed Mexico in terms of total employment costs back in 2015,” says Kevin Keegan, a partner in PwC’s consulting business. “If you think about the USMCA [U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement], and you think about fairly heavy goods that were made in China, making those in Mexico now is actually a better cost proposition for the North American market.”

Global companies aren’t abandoning China, however. Many have spent decades building relationships there, and Chinese manufacturers have developed know-how that can’t be found elsewhere. In addition, migrating from China “requires a lot of spending,” Keegan notes, which means a lot of planning. Still, he says, “we do expect that in the next six months or so there will be more of an effort to reconstruct the supply-chain footprint.” Patrick Van den Bossche, a partner at the Kearney consulting firm, says, “The trend that started as moving away from China as a single source has now matured into a trend of companies trying to geographically diversify.” The emerging model is sometimes called China-plus, a more stable kind of globalization for importers, while China prospers by producing more sophisticated exports and increasingly basing its economy on domestic consumption.

Exporters need to be nimble. As globalization morphs, canny exporters can thrive. Some, especially in China, the world’s largest exporter, are shifting toward domestic markets. Online marketplace Taobao announced last year that the number of exporters opening stores on its mostly domestic shopping site rose 160% from February to May. As then–Commerce Minister Zhong Shan said, “When there is no light in the West, there is light in the East.”

Some exporters also realize that they needn’t be tied to their home country. Several Chinese manufacturers, including TV maker TCL and textile producer Huafu, have set up operations in Vietnam. Chinese developers started building industrial parks in Mexico years ago, and the advantages of being there have grown stronger post-pandemic. Exporters, like importers, are learning that diversification pays off in today’s globalization.

Tumultuous times produce big winners and big losers in business, research finds. It’s happening again. In the new Global 500, 45 new companies pushed incumbents off the list versus just 26 replacements a year ago. We’ve entered a new world with new rules—a rich opportunity for the bold.

This article appears in the August/September 2021 issue of Fortune with the headline, “Global trade’s new playbook.”

Subscribe to Fortune Daily to get essential business stories straight to your inbox each morning.