BP’s capital markets day in late February would be an “exciting” event, CEO Murray Auchincloss told the crowd of analysts and employees at the British oil giant’s London headquarters, his eyebrows raised. He took a sip of water and began: “Today is more than an update,” he said. “Our strategy is being fundamentally reset.”

Even that may have been an understatement. Five years ago, with much fanfare, BP launched plans to lead Big Oil into the energy transition—investing heavily in green power while promising to axe oil and gas production by an astounding 40% by 2030 and aiming for zero net emissions by 2050. Then CEO Bernard Looney told Fortune, “I really think this direction is unstoppable,” adding, “Without action, it is a rather bleak future for the world.”

Be that as it may, the approach hasn’t impressed investors. BP didn’t fall into any obvious green energy boondoggle. Under Looney (who left in 2023), the company dived aggressively into wind, solar, and electric-vehicle charging infrastructure. But profit margins in wind and solar weakened, and the EV adoption curve moved slower than expected, making BP’s big moves look premature. That, coupled with the loss of political will behind clean energy subsidies in the U.S., has made it clear that oil and gas will remain dominant for longer than green advocates had hoped.

Meanwhile, BP’s scaling back on oil and gas production came amid surging fuel and power demand after the pandemic, an ongoing Russian war in Ukraine, and a burgeoning AI construction boom. Just as oil and gas became highly profitable again, BP had less of it to sell.

Now BP is formally changing course. The company said in February that it will increase oil and gas exploration and production spending by almost 20%, while selling off many clean energy assets—part of $20 billion in overall divestments through 2027.

Sitting down with Fortune at BP’s U.S. headquarters in Houston, Auchincloss said BP’s dive into the energy transition went “too far too fast” and became “wickedly capital-inefficient.”

“We just chased too much. We should have narrowed that. That’s obviously what I’ve done now,” Auchincloss said, adding that BP will add extra oil and gas volumes while still investing at a more modest pace in renewable energy. “Stick with what you’re good at and continue to grow…because that’s what nations want.”

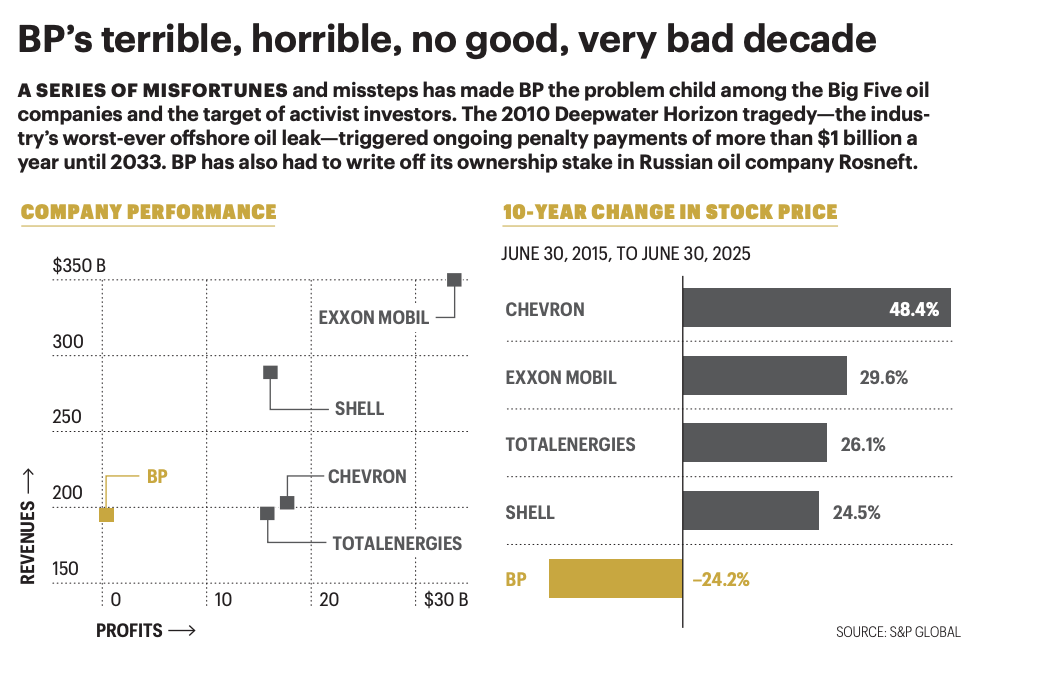

BP is hardly the only company downscaling its clean-energy promises, but BP’s shifts and struggles have proved the sharpest—and it has far less room for error. As industry leader Exxon Mobil counts a market cap near $500 billion as of mid-July—near all-time highs—BP sits at $85 billion, struggling mightily since peaking almost 20 years ago. (Back then it was No. 2 on the Fortune Global 500, one spot above Exxon Mobil.)

Ben Dell, cofounder and managing partner of activist private equity firm Kimmeridge, said this reckoning is overdue, that Big Oil must reposition itself after forgetting a fundamental rule of business: “Philanthropy is not an investing strategy,” he said. “The majors sort of lost sight of this, but wherever you invest your dollars, they have to be cost-competitive.”

With BP and archrival Shell now both London-based, longtime rumors escalated in late June to reports of Shell entering early talks to buy BP. That would be the biggest energy deal of the century—if not ever. Shell quickly denied any such negotiations, but the rumblings won’t disappear anytime soon.

And the pressure on BP is growing as aggressive activist investor Elliott Investment Management has built a 5% stake in the company and is pushing for major divestments—especially in clean energy.

BP is a 116-year-old company with roots dating back to exploration in Iran as the Anglo-Persian Oil Co. The name change to British Petroleum came in 1954.

To its own credit or misfortune, BP was the first Big Oil player to embrace the challenges of climate change. In 2000, it infamously rebranded as “Beyond Petroleum”—but operational and safety problems arose following a wave of rapid acquisitions before BP could develop a firm strategy, and the effort was widely derided as “greenwashing.” The name did not stick.

Then came the deadly 2005 Texas City refinery explosion; the 2006 Prudhoe Bay oil spill in Alaska; and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon tragedy—the industry’s worst-ever offshore oil leak. That disaster led to billions of dollars in asset divestments and ongoing penalty payments of more than $1 billion a year until 2033.

The company took another blow via its Russian operations: In 2013, Russia’s Rosneft bought out BP’s 10-year-old TNK-BP joint venture in Moscow, giving BP a 20% ownership stake in Rosneft. The deal seemed sound at the time: Rosneft quickly accounted for a third of BP’s oil and gas production and BP regularly received more than $1 billion a year in dividend payments.

But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 upended the arrangement. BP technically still owns the Rosneft stake, but it has already written off $24 billion in charges—an apparently lost investment.

Here, again, it is not alone, but it fared even worse than its Big Oil peers: Exxon, for instance, wrote off only $15 billion in Russian investments in 2022.

To put these challenges in context: Rosneft and Deepwater Horizon represent some $2 billion in lost revenues annually. That’s one reason BP posted just a $381 million profit in 2024. (The first quarter of 2025 resulted in a $687 million profit.) “They’re not getting that cash,” said Jason Gabelman, managing director of energy equity research at TD Cowen. “That makes it difficult to outperform.”

To add to the pile of BP’s problems: A larger share of its oil and gas production—about twice its peers’ percentages—is tied up in profit-sharing agreements with other countries or joint venture partners.

“And then there’s the volatility on the strategy,” Gabelman added. “Changing your strategy three times in five years is never a good thing.”

Having failed to move “Beyond Petroleum,” the question now is whether BP can implement its reset successfully, or if investor impatience will set in, forcing a sale. It remains to be seen whether the industry will move beyond RP.

When Bernard Looney took over as CEO in early 2020, the Irishman’s bold and camera-ready personality matched his aggressive green agenda. But his strategic missteps and previous romantic entanglements with employees combined to force his sudden resignation in September 2023. (BP said in a statement about his departure at the time that he “accepts that he was not fully transparent in his previous disclosures.”)

Then–chief financial officer Auchincloss reportedly was given roughly 20 minutes notice before he was named interim CEO. Four months later, the interim tag was removed.

“Changing your strategy three times in five years is never a good thing.”

Jason Gabelman, Managing Director of Energy Equity Research, TD Cowen

Auchincloss is a mild-mannered Canadian who joined Chicago-based Amoco in 1992 as a tax analyst before it combined with BP in 1998 in a nearly $50 billion deal. He later served as chief of staff to former CEO Bob Dudley, then as upstream CFO for oil and gas, and then as corporate CFO.

But Auchincloss isn’t a stereotypical numbers guy reluctantly bumped up to the top job. A fourth-generation oilman, he grew up in the oil-rich province of Alberta and started helping his geologist father pick oil and gas drilling targets at age 14. “How strange is that?” Auchincloss said with a grin. “I’m not an engineer, I’m not an expert, but I know enough to be dangerous.”

Auchincloss took over an energy juggernaut in decline that required a strict financial overhaul. “What

we really need to focus on is concentrating the portfolio and then hardcore delivery,” he said. “I think having the performance edge of a finance person is exceptionally important.”

Signs of that finance-guy discipline include BP’s sale of its U.S. onshore wind portfolio, divestment of a 50% stake in its Lightsource solar business, and the sale of much of its global offshore wind

business through a new, fifty-fifty joint venture with Japanese utility JERA. BP also sold a $1 billion stake in the TANAP gas pipeline from the Caspian Sea to Apollo Global Management. A strategic review of its $8 billion Castrol lubricants business is ongoing, and its retail fueling businesses in the Netherlands and Austria are being sold.

With its renewed emphasis on growing oil and gas production, BP is focused largely on expansions in the U.S. and the Middle East—from the Kaskida hub in the Gulf of Mexico to the Kirkuk oilfield in Iraq.

At the end of 2019, before its clean energy drive began, BP churned out 2.7 million barrels of oil and gas per day. That had fallen to 2.24 million barrels of oil equivalent daily by the first quarter of 2025—a dip of 17%, which came just as the world demanded more oil and gas. BP now aims to raise that back up to 2.5 million barrels daily by 2030.

Already this year, new natural gas projects have come online in Mauritania, Senegal, Egypt, and Trinidad. Three new U.S. Gulf oil and gas expansions are due to start producing in the next two years, and other major projects are slated for the decade’s end.

By 2030, at least 40% of BP’s total production is expected to come from the U.S. alone—both from the Gulf and the onshore BPX Energy business (the “X” stands for exploration) in Texas and Louisiana.

Some energy analysts have wondered out loud if BP should spin off or sell BPX, which could fetch close to $10 billion. But Auchincloss and BPX CEO Kyle Koontz—who resembles an older, Texas-bred version of famed Mexican boxer Canelo Alvarez—see the BP-BPX combination as a crucial growth engine.

“You’ve seen a lot of large-scale operators exit the [U.S.] shale business, including Shell,” Koontz said, then added a pugilist’s jab: “But when they exited, they weren’t competing. They certainly weren’t competing with the best…That’s what’s different about our group. If you have a winning team, and you’re competing head-to-head with the best, trading that away makes about as much sense as trading [NBA star] Luka Doncic.”

“Big Oil” is a term that used to include a larger group of the world’s multinational, publicly traded energy companies— the supermajors. Now it’s down to the Big Five: Exxon, Chevron, Shell, BP, and France’s TotalEnergies—and it could well shrink further.

Shell wants more acquisitions, but to pull off the purchase of BP, Shell would face a slew of regulatory and organizational hurdles. The other potential buyers for BP—Exxon and Chevron—are coming off or are amid other massive acquisitions. And the U.S. supermajors could have greater antitrust challenges even if they were interested, said Deborah Byers, senior advisor at energy research and investment firm Veriten.

“The cultural and social issues are huge,” Byers said. “Do shareholders really want growth? Or do they just want capital discipline and returns? It’s been a while since anyone has been rewarded for growth in this sector.”

And it has been a while since BP grew at all.

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the location of the 2006 Prudhoe Bay oil spill. It occurred on land in Alaska.

This article appears in the August/September 2025 issue of Fortune with the headline “Big Oil’s green retreat.’”