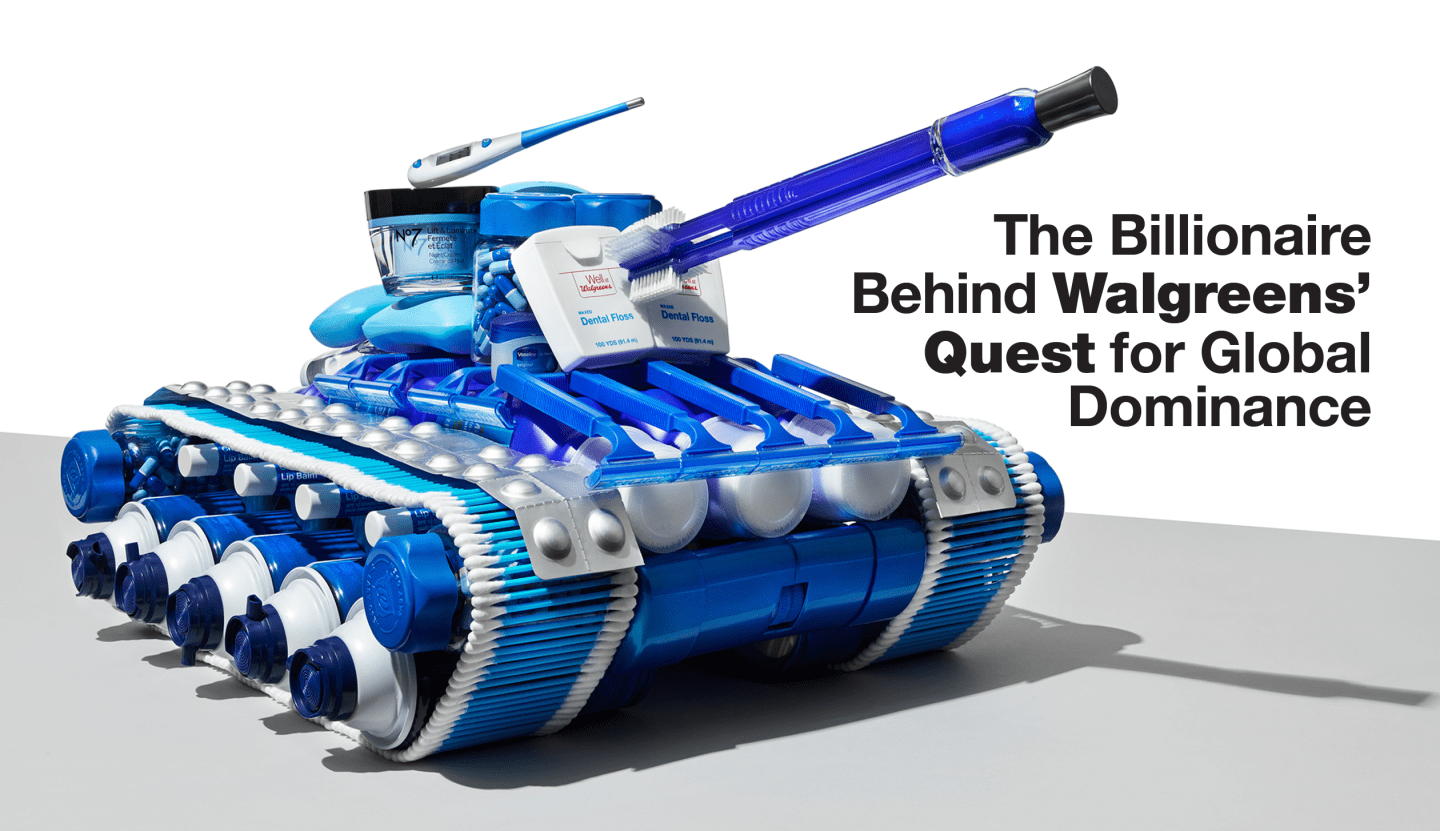

In early 2016, U.S. druggist Walgreens had recently bought Britain’s popular Boots Alliance chain to create the first international drugstore empire. The acquisition was the brainchild of Italian billionaire and dealmaker extraordinaire Stefano Pessina, and a deep dive by Fortune asked “Can a brilliant dealmaker become a killer retailer?”

Almost a decade later, we have an answer: a resounding “no.” As detailed in my recent Fortune feature, Walgreens has stumbled mightily in the last decade. Its value on the stock market was $100 billion in 2015, but by the time Walgreens Boots Alliance struck a deal to be bought by a private equity firm, Sycamore Partners, and go private after 98 years on the stock market, the company’s market cap had fallen 90%, to $10 billion.

Pessina, who will remain a major shareholder after the take-private deal, was better known for his dealmaking prowess than his skill at running stores. “I am not a retailer,” he admitted to Fortune’s Jennifer Reingold in 2015.

Ignoring retail in favor of deals has turned out to be a big factor in Walgreens’ decline. Under Walgreens’ business model, the front-of-store general-merchandise sales and its prescription business feed off each other. But over time, Walgreens, which is now closing some 1,200 stores out of 8,700, has let its stores deteriorate and became an e-commerce laggard. It hasn’t helped that Walgreens, like many large pharmacies, has locked up much of its store inventory to ward off shoplifters—a move that ended up warding off many shoppers too.

Meanwhile Pessina, who bragged in 2015 of having done 1,500 M&A deals in his life, kept making deals. With his eye on competitor CVS, he made a bid for Rite Aid, the distant No. 3 in the U.S. drugstore wars, and its 5,000 stores—an expensive adventure that later led to the closing of many of the 2,000 Rite Aid stores that regulators allowed it to buy. Other deals followed as Walgreens sought to mimic CVS’s focus on health care clinics, but many of those acquisitions have been unwound since, at a loss of billions to Walgreens.

A re-read of the 2016 Fortune piece underlines the lack of progress on key problems analysts were concerned about. Back then, Wall Street worried about Walgreens being pinched by tightening reimbursement rates for the drugs it dispenses and the fact that, unlike CVS with its Caremark, Walgreens didn’t own a pharmacy benefits manager to exert more influence on drug companies. Walgreens is still feeling the reimbursement pinch and still has no PMB of its own. And in 2015, there were also worries about Walgreens’ enormous debt load from its Boots acquisition, which stoked fears it had too little room for error as it attempted to turn around. Analysts are expressing exactly the same fears today.