It was January 2020 when Founders Fund partner Delian Asparouhov posted a selfie of himself in a “Make America Great Again” hat—the beginnings of a challenge to himself where he would wear the hat for a full month. People sent him chiding text messages about his tweet, he says. Business Insider published a story about it. One founder asked him to leave the hat behind when he showed up to a board meeting. (He obliged, Asparouhov says.)

“Times have changed,” Asparouhov tells Fortune.

Come this past election, Asparouhov says he was congratulated when he tweeted out his support of Trump. He now has friends serving in official or advisory positions in the White House. As a space cofounder and investor, Asparouhov says support for Trump in his circles has become “consensus”—or at least a willingness to support some of Trump’s policies or positions.

Some of the people once considered to be on the fringes of tech society—people like Palmer Luckey, who was fired from Meta in 2017 after a donation he made to a pro-Trump group led to speculation that he was associated with members who had made racist comments online—are suddenly back in vogue. Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz of Andreessen Horowitz, one of the venture capital industry’s most renowned investors, stunned the industry when they endorsed Trump in 2024 arguing that he would be better for “little tech, and—to the surprise of many—their firm hired as a junior investor Daniel Penny, a former Marine with no investment experience who had become a right-wing cause célèbre after being arrested for the death of an erratically behaving homeless subway rider he put in a chokehold (Penny was found not guilty of criminally negligent homicide).

This story was featured in The Reader, a weekly newsletter of the biggest stories from Fortune. Sign up here.

Several other influential tech founders and investors who once supported Democrats came out for Trump, including Zynga founder Mark Pincus and former Facebook exec David Marcus. Since Trump’s inauguration, the proverbial “red pill” (a Matrix film reference adopted by the right-wing to signify the moment someone’s political perspective shifts) is finding a market in Silicon Valley.

“There is a streak of conservatism much bolder now in the Valley than it’s ever used to be,” says Gilman Louie, an early investor in Palantir when he ran the CIA-funded venture capital firm In-Q-Tel, who is now managing partner of America’s Frontier Fund, which has an investment firm and non-profit organization focused on frontier and defense technologies.

Outsiders may be tempted to believe it’s just a few, high-profile outspoken voices who have veered to the right and are spending time in Washington D.C. or Mar-a-Lago—people like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, or David Sacks. But those who have spent time in the Valley since the Trump inauguration speak of a deeper-rooted cultural shift that’s been underway ever since—in the conservative ideas people now feel comfortable discussing openly, or in how some Democrats or centrists suddenly feel pressure to self-filter in public on once uncontroversial topics like DEI efforts. Among those who worked on diversity efforts and programs that once enjoyed seemingly broad support, there is angst that the gains are now on shaky ground.

There was an underlying unease in many that was evident during the reporting of this story. Fortune interviewed more than a dozen people—most of whom expressed they were too nervous to go on the record or refused to discuss certain topics. When my conversation with one investor I was meeting with in Palo Alto turned to politics, they turned over my phone that was sitting on the table in front of me—telling me they just wanted to double check I wasn’t recording.

“I think that people are still trying to gather their own talking tracks on this,” says one female investor, who asked to stay anonymous to keep from drawing political attention to her fund.

‘Obama’s staff is taking over Silicon Valley’

A couple of decades ago—when tech investors were spending most of their time on software, the distance from Washington, D.C. felt as wide as the approximately 2,435 miles by plane between them.

But in the last 15 years—as developers began to patch together social media platforms, train large language models, and mint digital currencies—all of that changed as politics and legislation started to threaten returns and profits. Many of the largest venture capital firms and tech companies have even brought on their own teams of policy staffers to help drive the legislation their way.

The cozying up was already taking place in 2008, when Former President Barack Obama—who had successfully used social media and digital platforms to rally votes—tapped executives at Uber, Google, Twitter, and health tech startups to work in his administration. Google’s then-CEO Eric Schmidt served on Obama’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. And the U.S. Digital Services Department he set up during his second term—which, as of a January executive order, has now been reconstructed into the Elon Musk-orchestrated “Department of Government of Efficiency,” or “DOGE”—had in 2014 been helmed by Mikey Dickerson, a Google engineer who rejiggered the U.S. government’s healthcare website.

After Obama’s eight years in the White House, a slew of his staff would leave politics to go work in tech—joining Airbnb from the CIA, or PayPal from the White House. The trend became so pronounced that CNN published a story in 2016, claiming that “Obama’s staff is taking over Silicon Valley.”

The distinction today is less that Trump is recruiting techies and investors to advise him on policy, which has precedent—but that the tech elite taking those roles now self-describe as Republican.

It’s well documented by now how the relationship between the White House and the tech community had frayed under former President Joe Biden. The Federal Trade Commission had blocked M&A deals—stifling opportunities for big founder and venture capital payouts. The Securities and Exchange Commission sued high-valued crypto companies like Coinbase. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, an independent agency funded by the Federal Reserve, started regulating payments companies like PayPal and imposed rules on buy now, pay later companies like Affirm and Klarna that gave them obligations more akin to credit card companies.

“As the calls for increased regulation, higher taxation, and corporate breakups from the left grew louder, many once-loyal Democrat tech leaders began reexamining their loyalties,” Louie of America’s Frontier Fund said, noting that many started to feel “let down by a progressive left that blames them for society’s ills” and so have shifted to a conservative free-market right.

An important concern was how a Democratic administration would approach AI—particularly as the European Union rolled out its own sweeping new policies that AI founders warned would stifle innovation and prevent them from competing with Chinese rivals like DeepSeek. President Biden had already introduced an executive order that AI founders said would hold them back.

“Silicon Valley is always worried about any administration coming out with heavy regulations on new technology—and not understanding the unintended consequences on U.S. innovation,” says Umesh Padval, a managing director at Thomvest Ventures, who invests in cybersecurity and AI companies.

Meanwhile, limited partners have consolidated their fund relationships as IPOs and M&A have dried up—making younger or newer venture capitalists less likely to be outspoken on controversial topics as they try to fundraise.

Trump supporters in the Valley

Phil Libin, the cofounder of Evernote who now runs the startup studio All Turtles and video startup mmhmm, told me he was taken aback during his latest trip to San Francisco in late January. Libin, who had moved to the red state of Arkansas during the pandemic, was surprised by the wide support for some of the efforts to reduce bureaucracy, like DOGE, that he heard about while he was there—and how split people seemed to be over Trump.

“It was just strange for me going back there and realizing that actually there were probably as many Trump supporters in the people that I talk to in San Francisco than in Bentonville, Arkansas—maybe more,” he says.

Libin says “it was always uncommon” to find anyone who backed Trump in the last decade. “Now, it really felt like—at least in the places where I was—it was maybe 50/50.”

Someone else, who works in product at a health tech startup and who asked to speak anonymously because they feared repercussions from their employer, told me almost everyone he has met who worked in tech in the Bay Area since he moved there two years ago had been pretty liberal. But that started changing last year. He mentioned a Christians in Tech event he had attended last year at YC Combinator CEO Garry Tan’s home, where Peter Thiel had spoken. “Some of it was maybe religion-related, but a lot of it was more [about] conservative philosophy,” he recalls.

Several techies—both Republican and Democrat—expressed that it was good to have different perspectives in the Valley, but that it was important that different ends of the political coin feel they can express their viewpoints.

“I do think that Conservative voices were all silenced for a long time, and that has kind of been rebalanced over the past year. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing,” says Leslie Feinzaig, the early-stage investor who, last year, had put together a “VCs for Kamala” petition that had mustered more than 875 signatures from well-known investors who pledged to vote for the Democratic candidate. “I think the bad part is when the pendulum swings so far into one direction, everybody in the center can’t say anything else.”

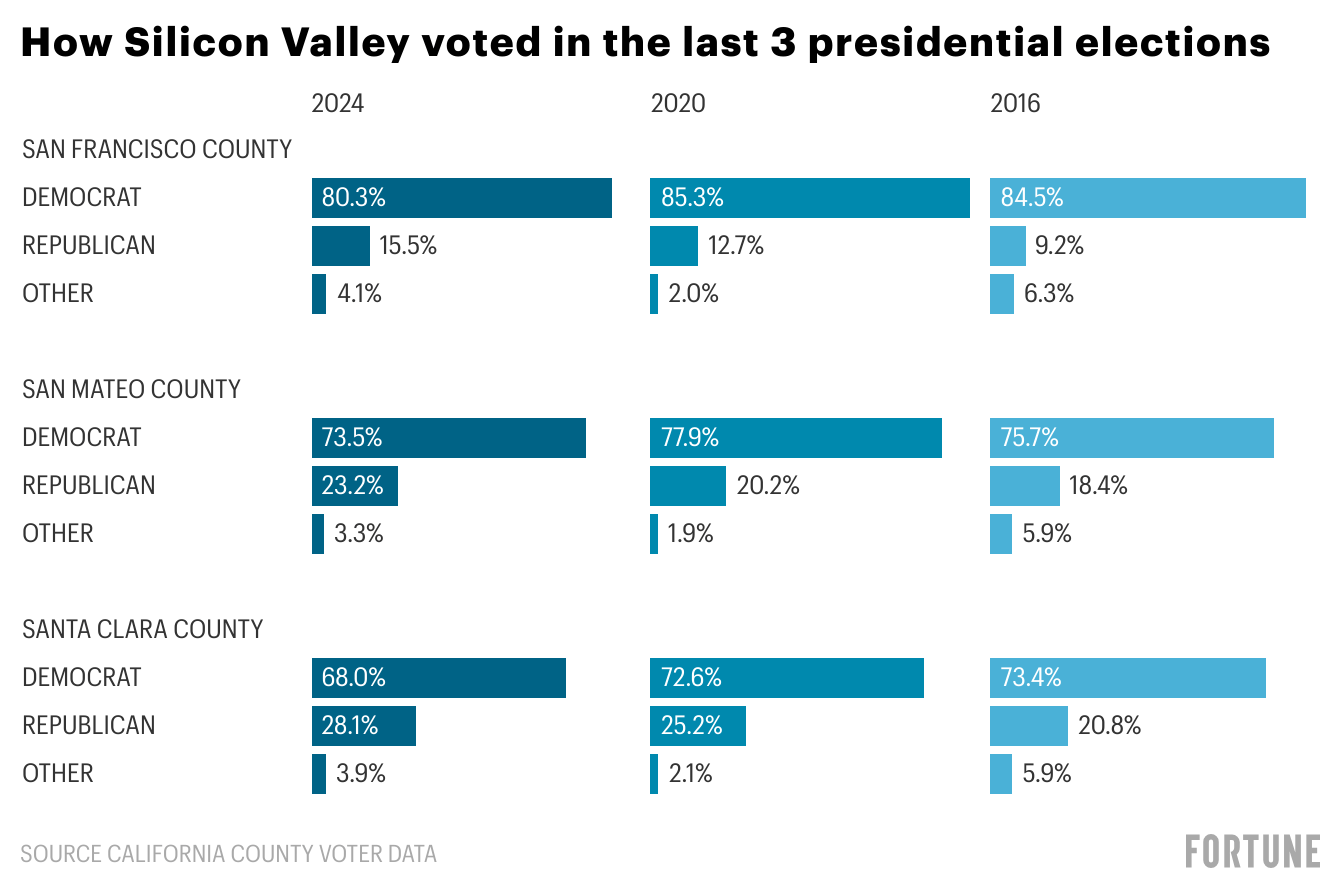

Silicon Valley continues to be predominately blue—certainly on paper. Throughout San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara counties in California, which encompass the area described as the “Valley,” Kamala Harris captured at least 68% of the votes in each county—even though Donald Trump won an additional approximately 3% of the vote in each County compared to the 2020 election.

But insiders say that there’s been a change in the tide post-election—an acceptance of conservative viewpoints, or, as some describe, an “embrace” where it hadn’t been before.

“Post-election, people feel more comfortable espousing views,” says Venky Ganesan, a partner at Menlo Ventures, a Silicon Valley VC firm that he says has an institutional policy prohibiting its managing partners from donating to or endorsing a presidential candidate. “My sense is they had them privately, but just now feel comfortable expressing them.”

Tech industry insiders pointed to Luckey as someone now considered to be less controversial. And suggested that founders like Brendan Eich—who had stepped down as CEO of Mozilla a decade ago after outrage over a small donation he had made to a campaign to ban same-sex marriage in California in 2008—may have had a different fate should these donations have surfaced today.

Unlike their Bay Area peers, techies who were based in New York or other tech hubs told Fortune they hadn’t really felt a shift in-person—only online.

On social media—and specifically X, “this feels like a totally new industry,” says Feinzaig. But, she notes, “when I meet with founders, when I talk to other investors, when I connect with LPs—you know, a lot of people’s values have not changed,” Feinzaig says.

DEI on the chopping block

Even among those committed to progressive ideals, however, it’s impossible to ignore that values once embraced in Silicon Valley are now under siege. In January, Meta started rolling back its DEI programs—ending requirements to consider diverse candidates in job applications, halting efforts to source diverse business suppliers, and removing its internal DEI team. Google followed suit shortly after.

In D.C., President Trump signed an executive order the day of his inauguration requiring government agencies and departments to terminate all contracts related to “diversity, equity, and inclusion” and to provide details about all their programs and employees.

The moves have caused a quiet distress among supporters of the programs. Over the last decade, a series of venture funds, accelerators, or fellowship programs have emerged that focused particularly on entrepreneurs who had been underrepresented in Silicon Valley in some way—whether because of their race, gender, or sexual preference and identities—as these groups only get single-digit percentages of venture capital funding each year. Many venture capital firms had funded, backed, or been involved in these programs—and some limited partners, including CalSTRS or the New York State Common Retirement Fund have specific programs or investment theses to back diverse managers.

A partner at a New York-based venture firm that launched a diversity-focused fellowship for startup operators in the last couple of years, said she believes that “everyone who champions and who holds the value that diversity is a benefit is definitely both feeling an affront to those values, and is also taking a step back to understand what the legal risk is.” The partner spoke on condition of anonymity, as she was worried about attracting DEI-focused legal attention to their fund.

In many cases, says Feinzaig, the conversations about how to react are happening in private. “A lot of people are going to hold their voices about how they view what is going on—both in Silicon Valley and in Washington, D.C., and kind of across the tech industry at large—because it’s unclear what the repercussions for speaking up are going to be today,” she says.

One month in

If it’s frustration with the Biden Administration’s policies that drew techies to Donald Trump in the first place, the new president will still have to win favor.

Some elements of the Trump agenda will be a tougher sell in Silicon Valley than rolling back regulation has been. Trump’s crackdown on illegal immigration and on refugee and asylum-seekers, for example, may not be popular within tech companies, many of which have been founded and built by immigrants. Some companies have been issuing warnings to employees with H-1B visas or urged them not to travel.

Mostly, people agree that Silicon Valley’s MAGA vibe is only just starting to play out—and that one month in, Trump must still show that he can open up the IPO market and spur a wave of unimpeded M&A deals to cement his gains into the tech world. But there are some things that should be of no surprise. “As venture capitalists, you should not be surprised that we believe in capitalism,” says Menlo Ventures’ Ganesan. After all, it’s in the name itself.