Let’s do a simple thought experiment. Assume that tonight we redistribute the country’s income and wealth so that everyone has the same amounts. That would have enormous consequences, including on wages and prices. Chauffeurs’ wages would go down; childcare workers’ wages might go up. Prices of beachfront properties in the Hamptons and on the Riviera would go down; prices of land elsewhere might go up.

Bernard Arnault and his family, owners of the luxury goods conglomerate LVMH (which owns a host of brands like Christian Dior and Moët Hennessy) and one of the richest families in the world, might not be so rich if there were not so much inequality. They have absolutely thrived on it. But if the distribution of dollars is the result of exploitation today or in the past—as is the case—then the prices and wages that emerge even in a competitive market lack moral legitimacy, even if the rules today were set in a morally legitimate way.

This should make clear that even in perfectly competitive markets the magnitude of the rewards may have no fundamental moral justification, even if there’s a strong moral or economic argument that people who work or save more should be rewarded for their hard work and willingness to save.

The case is even stronger after we come to understand the multiple distortions in the economy. No market economy even approximates a competitive ideal of perfect competition, perfect information, and perfect risk and capital markets. Each “failure” can have significant effects on prices and, therefore, on the opportunity sets of different people. And even small deviations from the perfections required by the competitive ideal have big consequences. This is one of the important implications of the information revolution in economics over the past forty years.

Freedom, moral claims, and redistribution

Consider an economy with large disparities in income and wealth. Should the government impose progressive taxes to fund public goods, like investments in basic research and infrastructure? I have argued that behind the veil of ignorance there would likely be consensus that the government should. Libertarians retort that everyone has a certain moral legitimacy to his own income, well deserved because of his hard work, intelligence, and thrift.

But think about what their incomes would have been had they been born in a poor country, without the rule of law or the institutions, infrastructure, and human capital that make the economies of advanced countries work so well. It is not enough to have assets such as entrepreneurial talents. If you are born into the wrong environment, those assets mean nothing. They yield the returns they do only because of the socioeconomic environment in which we live. And if that’s the case, we owe our income and the wealth that derives from it as much to that environment as to our own skills and effort. There is full justification, then, for imposing high taxes on high incomes even in a perfectly competitive economy in which wealth is garnered in ways that have full moral legitimacy.

Likewise, the moral claim against progressive taxes is slim if high incomes arise out of luck or inheritance—and even more so if they are made possible through exploitation or because the rules that generate or allow such incomes have been shaped by access to political power. There is no presumption that the laws and regulations are themselves set in a fair way even in a competitive economy. Quite the contrary, with political power linked to economic power and economic power linked to the economic rules set in our political processes.

Trade-offs in freedoms

In a society with a fixed amount of resources, expanding one person’s budget constraint—enhancing the freedom to spend—necessarily constrains others’. Redistributive taxation, of course, does this. Libertarians focus on the restraints that taxation imposes on the rich rather than on the loosening of the constraints on the people living in poverty who will have more to spend because of the income transfers or who will be better able to live up to their potential because of the education or health benefits they receive.

The world, of course, is more complicated; it is not “zero sum.” Taxes, as actually imposed, may reduce work or savings, and therefore national output, because they reduce the return to work or savings. The provision of better education and health can expand output enormously. How large the effects are in each case is a subject of debate; the magnitude clearly influences assessments of trade-offs.

Assessing the magnitude and nature of the trade-offs is hard, and it is the subject of inquiry of many an economist. I am of the view that conservatives typically exaggerate the adverse consequences of progressive taxation.

Some of the wealth of the very rich is the result of luck. To the extent that it’s luck, redistribution and funding better social protection may increase economic output. The randomness of outcomes discourages work and investment. A good system of social protection may encourage people to undertake high-risk, high-return activities. Corporate-profits taxation with loss offsets has long been seen as a form of risk-sharing, with the government as a silent partner, and long been shown to increase risk-taking and investment.

Some of the high profits are a result of skill, but often skill in exploiting others and creating market power. To the extent that effort is directed at rent-seeking, we want to discourage it because it decreases GDP and increases inequality. Taxes on monopoly profits curb incentives to create market power and, together with rules curbing exploitation, redirect effort to more constructive activities.

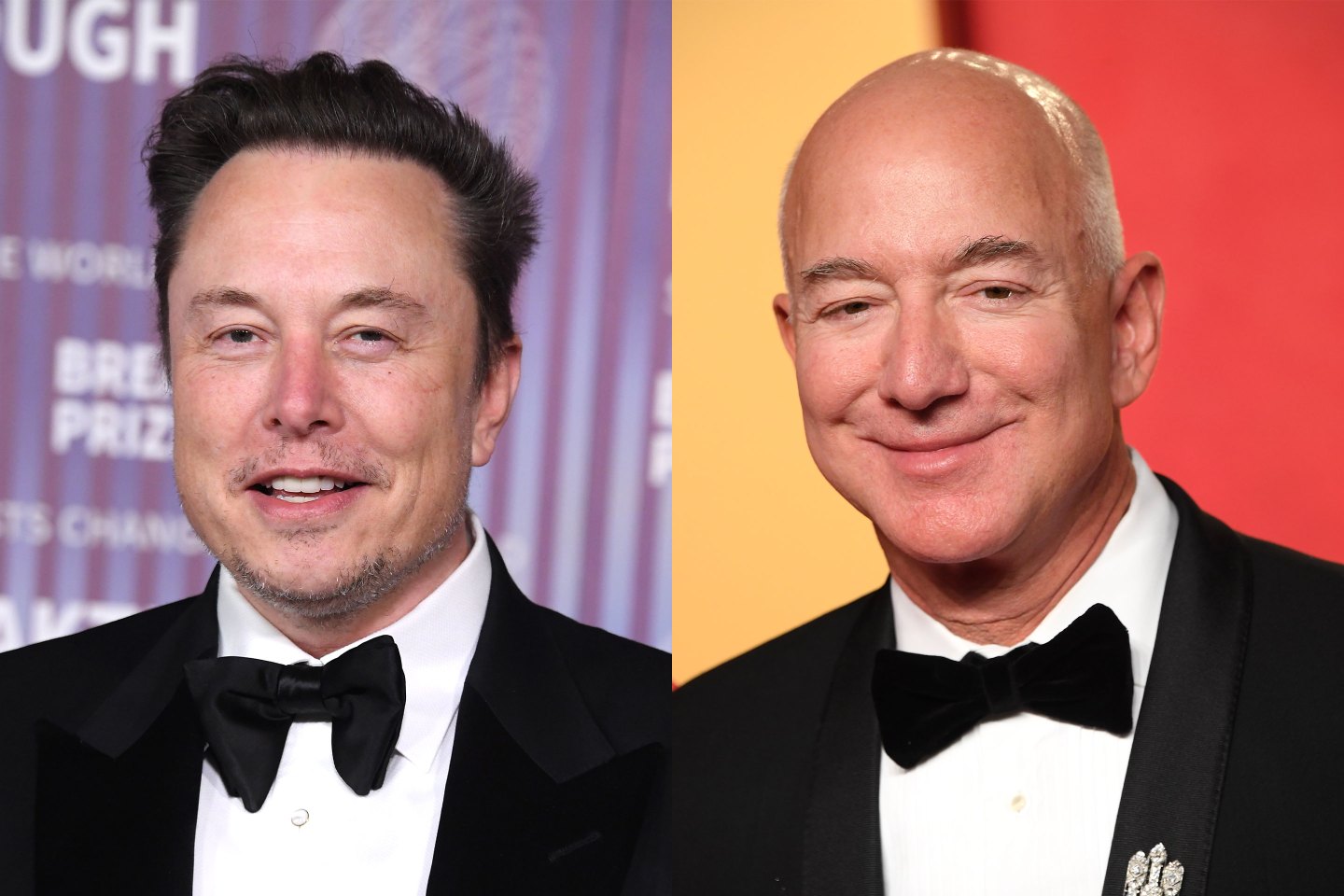

But even when efforts at the very top are focused on socially desirable entrepreneurship, it’s hard to believe that higher taxes, especially on exorbitant corporate profits, will matter much. Do we really believe that Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, and Elon Musk would not have accomplished what they have if they could take home only $30 billion rather than the massive amounts they do? These entrepreneurs may have been driven by money, but also by much more than that.

Excerpted from The Road to Freedom: Economics and the Good Society by Joseph E. Stiglitz. Copyright © 2024 by Joseph E. Stiglitz. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.