Anxious workers concerned that generative AI and sophisticated robots will one day endanger their job of choice should watch for a counterintuitive sign: rising wages.

As implausible as that sounds, the theory is backed by data from past eras when seismic technological innovations wiped out entire occupations, say economists behind a recent National Bureau of Economic Research paper.

The researchers found that when it’s commonly believed that a particular job category soon won’t exist, that field begins shedding employees. Some people make the jump to other professions, and predictably, fewer workers enter the doomed job category. That leads to a supply crunch for employers, who are in turn required to pay a premium—or what the study authors dub an “obsolescence rent”—to the role’s holdouts.

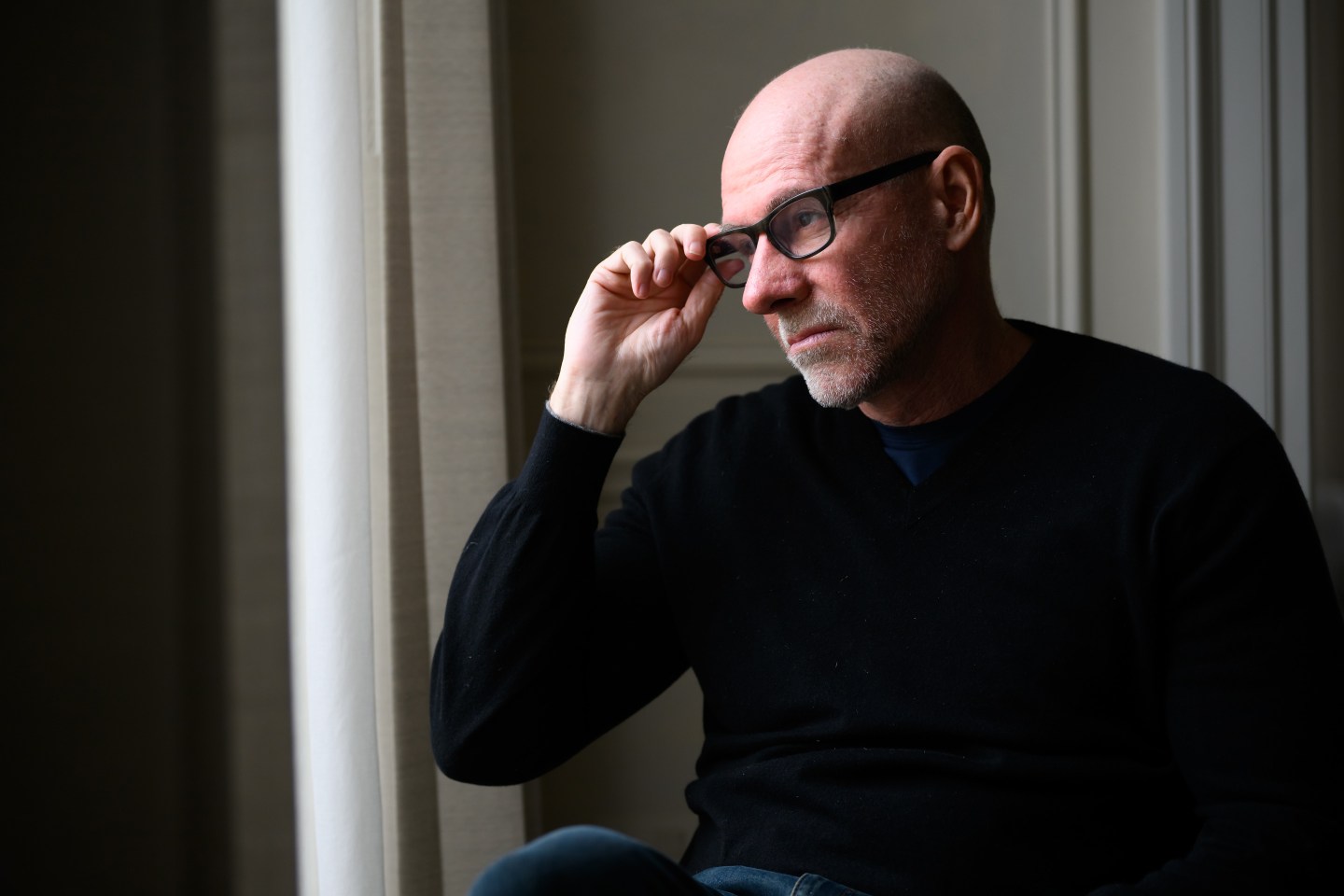

Costas Cavounidis, an associate professor at the University of Warwick who led the study, says today’s employees should refrain from jumping to conclusions about the health of an occupation based on its wages. When a major technological shock is expected, rising pay doesn’t always mean that a job category is growing.

The study also holds implications for business leaders, who should begin preparing for labor shortages that will mark what the study authors call the “anticipatory dread” stage of a job’s demise, otherwise known as the yearslong period when it appears that a technological revolution will eradicate a job role.

“The strategic firm right now would be hoarding labor in occupations that they expect will not be able to hire people in the future,” says Cavounidis. “I expect that in the medium term, it will be really hard to hire folks in particular occupations because of the threat of automation.”

Cavounidis’s group came to these conclusions after examining wage data for early 20th-century teamsters, men who once drove teams of horses pulling wagons with commercial cargo. Motorized vehicles wouldn’t completely replace horse-drawn wagons until after the First World War, but signs that engines were the future were apparent by 1910.

The threat of engine-driven trucks led to an increase in age among teamsters as younger workers avoided the job and those already in it sought safer occupations, including as truck drivers. The researchers presume that older workers stuck around because they’d be retired or close to retiring by the time newfangled motorized trucks drastically cut demand for their services. With the pool of available teamsters dwindling, wages naturally rose.

In short, leading horse-drawn delivery wagons in the final days before trucks took over would have been a lucrative job—but only until it evaporated completely.

The researchers found similar patterns in other jobs that were made redundant by technology. In their review of the history of dressmaking just before the rise of garment-making factories, they saw the same age-related shifts in the labor market.

Today’s truck drivers are also facing the threat of job loss to self-driving vehicles, Cavounidis notes, so it’s reasonable to assume that some wage increases and driver shortages are connected to a widespread fear of autonomous trucks. Today, he adds, “this job is not attracting young folks, and that may well be because the young folks don’t think the job will be there for very long.”

Cavounidis explains that he took on this study amid debate about AI and the need for job retraining to see how workers respond to worries about the future. More important, he notes that his team’s findings are tied to widespread speculation about a job’s fate and not whether there was any truth to predictions about a major tech-driven extinction event. Many of our biggest fears about AI may still prove to be unfounded, but they will still impact workers. Then again, if AI ends up stealing jobs very rapidly, there will be no adjustment period or “obsolescence rent,” Cavounidis says.

Ultimately, the scholars hope their work will inform government policies that can help protect workers in a rapidly changing job landscape. “We can’t tell you who’s at risk,” he says, “but I hope we might shed some light on what you should do once you’ve detected this risk.”

Do you have insight to share? Got a tip? Contact Lila MacLellan at lila.maclellan@fortune.com or through secure messaging app Signal at 646-820-9525.