Forty years ago, a 69-year-old candidate for President stood on a Cleveland debate stage 15 feet from the incumbent, turned to the television audience, and asked a question that would seemingly change the race overnight: “Are you better off than you were four years ago?”

It was Oct. 28, 1980, and opinion polls until then had been suggesting a close contest between the two nominees, former California Gov. Ronald Reagan, the Republican, and President Jimmy Carter, the Democrat—with the most recent of surveys splitting down the middle as to who had the edge. But the challenger’s question that evening, posed at the end of a cordial 90-minute exchange, clarified the choice in a flash. The American economy was wilting under the burden of “stagflation,” a portmanteau that roughly translated to “everything stinks”—the unemployment rate was mired at 7.5%, inflation was soaring, gasoline prices had climbed by more than a third in just the past year. Reagan, “the Great Communicator,” had framed those gloomy circumstances in a handful of words—and one week later he won the White House in a landslide, carrying 44 of the 50 states.

Four decades later, on the cusp of another presidential election, it might seem that there’s no question that’s more relevant to voters than the one Reagan asked—and a few pollsters, as you might expect, have already asked it. A September survey by the Financial Times and the Peterson Foundation found that a plurality of U.S. voters, 35%, felt better about their present financial situation, and 31% felt worse, compared with four years ago; a later poll by Gallup painted a more upbeat picture, with a clear majority of registered voters (56%) saying they were better off today. Both surveys would seem to portend good news for President Donald Trump as he faces off against former Vice President Joe Biden.

Yet here’s a surprise: The answers tell us little about how voters will actually fill out their ballots. “We’ve done a lot of research and have never really found a link between people’s own finances and how the vote turned out,” says Jeffrey Jones, who oversees all U.S. polling for Gallup, including the “better off” survey above. “People are not really self-interested when they think about how they’re going to vote, it’s really sociotropic voting: They care more about what’s going on out there as opposed to their own situation,” he says.

Far more predictive of election outcomes, says Jones, are a trio of Gallup surveys—those measuring Americans’ confidence in the economy overall, satisfaction with the way things are going in the U.S., and presidential approval—that look at the state of the nation as a whole. (In each, the President’s rating is currently underwater, and particularly so compared with previous incumbents who won reelection.)

The material question for voters, then, isn’t “Am I better off?” but rather “Are we better off?” Indeed, that was the true focus of the question Reagan framed 40 years ago, a fact that has been too often missed. As the candidate went on to prompt his TV audience in 1980:

Is it easier for you to go and buy things in the stores than it was four years ago? Is there more or less unemployment in the country than there was four years ago? Is America as respected throughout the world as it was? Do you feel that our security is as safe, that we’re as strong as we were four years ago?

U.S. voters today are facing additional questions that drive, perhaps, even more deeply to who we are as a nation: our shared sense of purpose, our trust in the institutions of government and society, even the way we talk and listen to one another. In every election, of course, voters will inevitably make personal choices on the basis of ideology, philosophy, or morality—as it should be. This year, though, there is one fundamental question that voters of every political bent ought to ask before they cast their ballot: Is the United States of America more or less united than it was four years ago?

Me vs. we

“Human nature really is the fundamental force that governs politics in any society at any time,” says Mike Leavitt, who was elected three times as governor of Utah and later served in President George W. Bush’s cabinet as secretary of U.S. Health and Human Services. “And this division between ‘Am I better off?’ and ‘Are we better off?’ is really the conflict between (me) individual liberty and (we) security: We give up one in order to gain the other.” Leavitt, a conservative Republican, sees the struggle between these two eternal goals—liberty and security—as a legitimate, and even necessary contest. But he is concerned with how brutal the battle has become, though he contends the vitriol has been building for far longer than in just the past four years. “We’re seeing people on both extremes who seem willing to color outside the lines, to break the covenant of democracy. And that offends us, and it scares us, because it’s not consistent with [the pact] we’ve all entered into.”

Data from the Pew Research Center shows how hardened the divisions between left and right, Democrat and Republican have become. Though the major parties are growing further apart on issues, the bigger concern is not ideological but personal. “Partisan antipathy—this is the sense that I not only disagree with the opposing party, but I take a rather negative view of the people in that party—has been growing since the mid-1990s,” says Carroll Doherty, the Pew Center’s director of political research. But in 2016, Doherty says, those negative feelings began to spike. The share of Republicans who describe Democrats as more immoral than other Americans grew from 47% in 2016 to 55% in 2019, according to Pew research. The share of Democrats who describe Republicans as immoral rose 12 percentage points, from 35% to 47%. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of Republicans surveyed by Pew said Democrats are more “unpatriotic” than other Americans (23% of Democrats feel the same about Republicans), and the share in each party who view the other as more “close-minded” or “lazy” than their countrymen has climbed as well. Overwhelming majorities in both parties say the divide between them is growing, with some three-quarters of Republicans and Democrats acknowledging that they “cannot agree on basic facts” when it comes to the views of the other side. Dispiritingly, Pew found, huge percentages on both sides of the aisle (53% of Republicans and 41% of Democrats) do not want their leaders to seek “common ground” with the other party if it means giving up anything.

Doherty emphasizes that Pew’s latest study was conducted a year before the presidential election—and before the coronavirus pandemic: “While we can’t extrapolate … it’s possible that these negative sentiments could have grown,” he notes.

“There is this existential struggle for the soul of America in which neither side can win, and it’s all about the threat of the other side,” says political scientist Lee Drutman, a senior fellow in the political reform program at the New America foundation. “We have half of the country who’s convinced that the other half of the country—if they got power—would be illegitimate and substantially destructive.” Drutman, whose book Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America was published in January, contends that the escalating hyper-partisanship has “simplified” politics into this us-versus-them, good-versus-evil binary.

Trump’s rhetoric has been an “accelerant” to the long-simmering anger on both sides, says Drutman. The fiery invocations he unleashed at his campaign rallies didn’t end when he got to the White House. They got louder and fiercer and were echoed on social media. Says Alan Abramowitz, a professor of political science at Emory University: “He went from dog whistles to a bullhorn”—from quietly tapping into racial, ethnic, and partisan resentment to stadium-size chants.

The high-decibel roar of his MAGAphone has had an effect that goes well beyond “rallying the base,” says Lilliana Mason, associate professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland, and author of the book, Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. It has encouraged and even normalized politically based violence, she says—pointing, for example, to the rise in “anti-immigrant” hate groups in the U.S., which has risen in parallel with the anti-immigration rhetoric of politicians. (The number of such groups has more than doubled since 2014, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.) “There are a lot of people warning about radical, mainly right-wing, violence specifically around the 2020 election,” says Mason, “but we’ve already seen heavily armed men walking through American cities.” To glimpse the potential danger, witness the brazen plot by members of self-styled militia groups to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, which was revealed by the FBI in October. These are things “we couldn’t even imagine in 2016,” Mason says.

A long to-do list

As much as this negative partisanship has torn America’s social fabric, it has made legislating all the more challenging—particularly at the federal level where “to get anything done, you have to be able to build coalitions that to some extent cross party lines,” says Abramowitz. Indeed, Drutman says the problem goes even deeper: “One of the fundamental conflicts in the American system is that we have political institutions that are set out to encourage broad compromise, and we have a party system that has evolved to make compromise very difficult. So we have a different set of electoral and governing incentives from the start.” The escalation in political vitriol only widens the gap between them.

To thrive over the next century—and in a world that’s more competitive, economically, than ever before—Americans must invest in the nation, just as any business needs to invest in itself in order to grow. That means funding job reskilling programs and rebuilding critical infrastructure, a sprawling mandate that spans from repairing crumbling roads and bridges to constructing advanced 5G telecom networks. The Social Security system did not get less wobbly on its own; it will need to be fixed somehow. We still have to rein in runaway health care costs, and get the still-raging pandemic under control, to say nothing of preparing for whatever outbreaks are yet to come. There are even knottier problems to contend with—climate change, criminal justice reform, crafting an immigration policy that sustains both industry, U.S. security, and a sense of fairness. And ultimately, we’ll have to find a way to put the millions of people who lost their jobs in the wake of COVID-19 shutdowns back to work (see our election package). It’s no small list of must-dos.

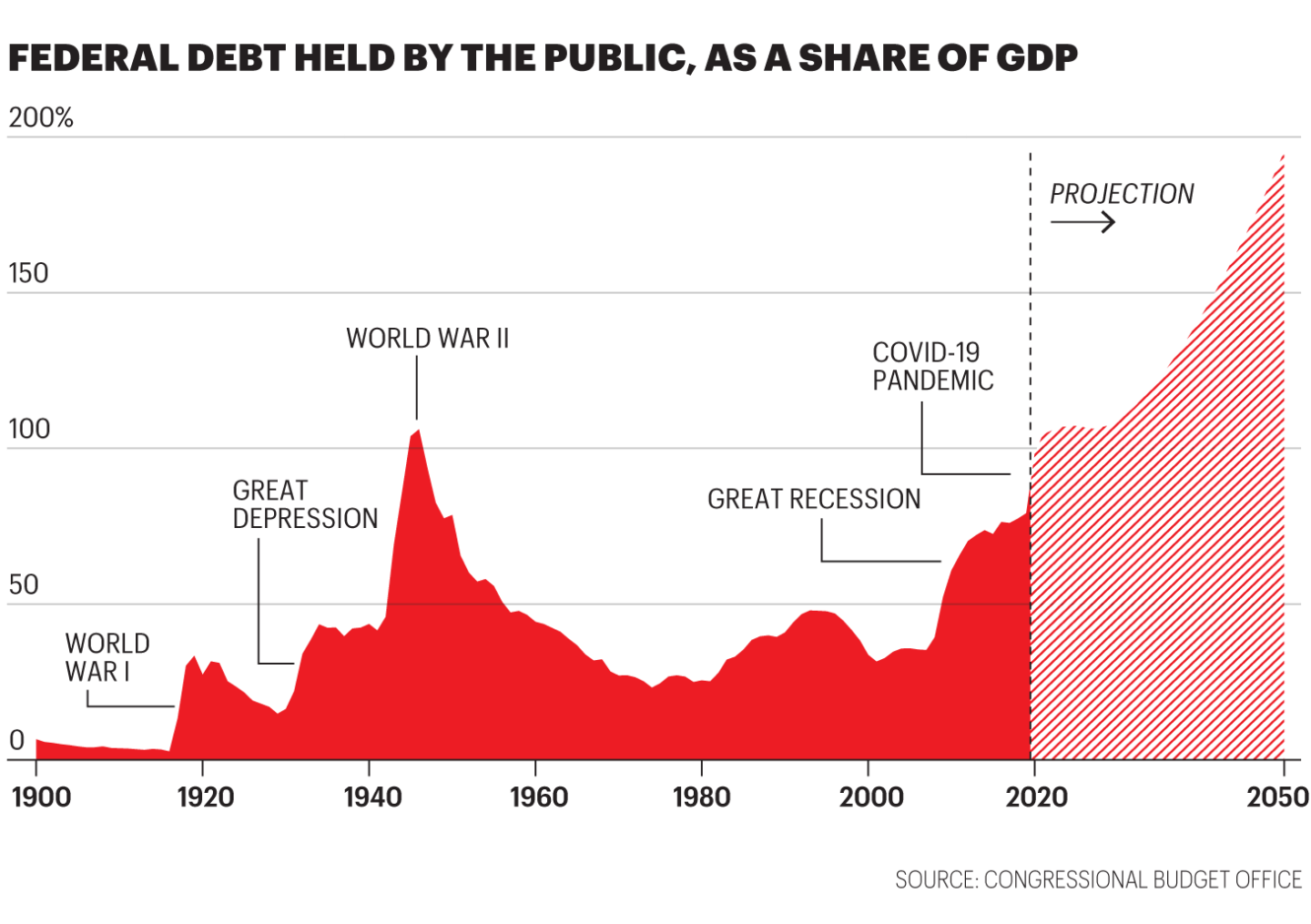

Paying for all of this is, if anything, a more daunting challenge: Our spendaholic leaders in both parties have already emptied America’s wallet, and we’re in hock up to our shorts. The federal debt held by the public will reach 106% of our GDP in 2023, according to the Congressional Budget Office (see chart)—and the fever line rises relentlessly from there. We’ll have to be creative and ambitious in our problem-solving—and, yes, that means the warring parties must set aside their bitterness and work together.

It also means we’ll have to hot-wire business growth in the U.S. “It sounds probably academic and otherworldly to say the solution is innovation,” says Edmund Phelps, winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Economics and director of the Center on Capitalism and Society at Columbia University. “But quite frankly, I’m not sure how far we can progress if we don’t get the economy to be delivering better than it has been for the past 40 or 50 years.” Phelps says he is happy that companies are starting to aggressively push back on Trump administration tariffs as well as on an immigration policy that is “blocking the talents that companies need for developing new products.” Phelps is particularly keen to see the next administration embrace international trade. “It could be a source of new energy in the business sector in this country. That will be great for jobs and wage rates and everything else,” he says.

Sandi Peterson, a member of the board of directors at Microsoft and a partner at Clayton Dubilier & Rice, a New York private equity firm, is equally frustrated with Trump’s immigration policy. “If we don’t get our act together, the innovation engine of the United States—where all the smartest people in the world showed up and created all this amazing stuff—is gone,” she says. “People won’t come here to study anymore. People won’t come here to try to work anymore, because they can’t get visas,” says Peterson, who was formerly group worldwide chairman for Johnson & Johnson. Luring talent from overseas “is what has driven the economy of this country for an incredibly long time—and we just really messed it up.”

The challenge for voters, on this front, is to guess what’s the best way to fix this: Give Trump another chance or clear the slate and start over.

Trust and credibility

Whoever ends up being in charge on Jan. 20, 2021, will have another urgent task: rebuilding trust in the institutions of government itself. Over the past four years, agencies that used to be considered nonpartisan and independent from political pressure—including the CDC, FDA, and the Justice Department—have been viewed by many with skepticism and suspicion, as they have seemed to bend to White House talking points. “All of these institutions used to be neutral arbiters,” says New America’s Drutman. “And in a political system where everybody can agree on a basic procedural fairness and can accept the idea of a legitimate opposition, then these institutions can maintain their independence.” But this is one more lost treasure, it seems, in our era of fevered hyper-partisanship.

Such infighting has implications for our national security, says the University of Maryland’s Mason: President George Washington warned against this in his farewell address, she reminds us. “If you allow factions to form, you open the nation to foreign interference because we start fighting ourselves,” says Mason. “When we create this very deep partisan divide, it makes us weaker as a nation, and it makes it much easier for other nations to mess with us.”

Brian Finlay, president and CEO of the Stimson Center, a nonpartisan think tank devoted to studying global security and other critical issues, agrees. “We’re now in a world where our adversaries have identified the fundamental weaknesses of our system,” says Finlay. “They’ve exploited the divisions. They’ve exploited the technology weakness that they’ve seen by convincing our children that the Washington Post doesn’t have credibility. Our adversaries have wised up, and now they’re attacking our elections, which is like shooting fish in a barrel. They don’t need to send armed combatants to the United States. They can do it from their basement computers.”

It is hard enough to defend against such asynchronous warfare. It is harder still to do it without alliances, partnerships, and pacts. The U.S. has long entered into multilateral agreements—to stem Soviet expansion and aggression in the Cold War, limit the spread of nuclear weapons around the world, prevent illegal fishing, and naturally, sell more American goods.

But in the past four years, President Trump has pulled us away from many of these critically important alliances—even “terminating” our relationship (in the middle of a global pandemic) with the World Health Organization, an institution that the U.S. pushed for, and helped create, in 1948. He has also scuttled the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement, which was “designed to implant a countervailing force against an aggressive China across Southeast Asia,” says Finlay. “Now China has managed to turn the scales on us, and we’re playing small ball on a country-to-country basis. We’re trying to convince the Vietnamese not to allow the Chinese to build dams on the Mekong instead of building a coalition of American interests that give us a global trading advantage.”

We also exited the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty that President Ronald Reagan signed with Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev in 1987, and which helped to end the Cold War. We abandoned the Open Skies Treaty, which had broad bipartisan support, and Trump yanked the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

These are yet more self-inflicted wounds when it comes to America’s health, prosperity, and security—and one more consideration for voters as they head to the polls. But let’s keep it simple: Are we better off than we were four years ago, or is it time for a change?

This article appears in the November 2020 issue of Fortune.