From 1991 to 1999, my job as Oregon’s secretary of state gave me responsibility for working with local government officials to protect and ensure the integrity of the state’s election system. It’s of paramount importance in a functioning democracy that votes—as our citizens cast them—are collected and counted fully and accurately.

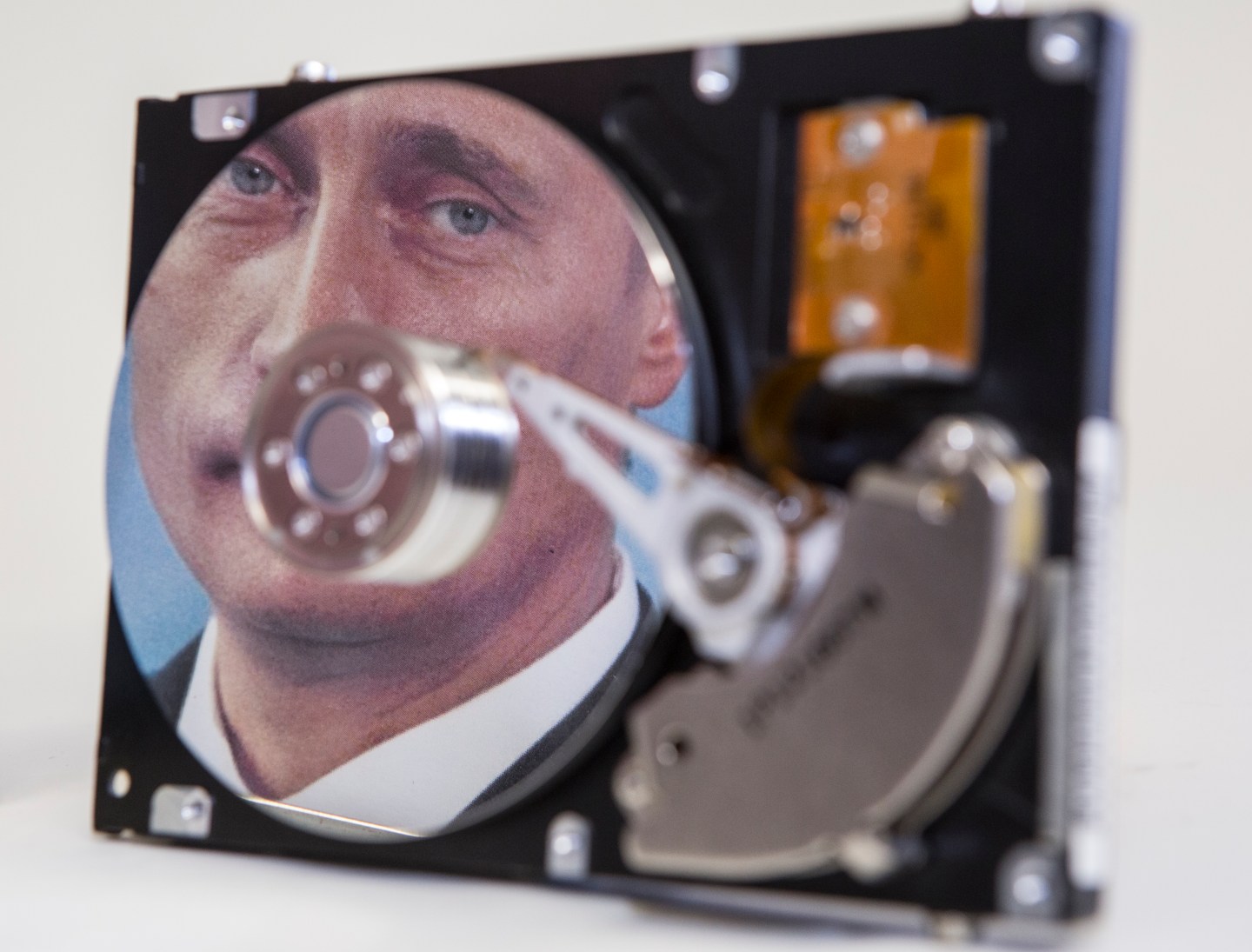

Recent revelations about Russian efforts to affect the 2016 presidential election have unsettled citizens and election officials alike. To date, there’s no credible evidence that actual votes were tampered with or miscounted due to a cyber attack. But there’s growing unease about the potential vulnerability of the nation’s disparate election systems—operated by 50 states and thousands of local governments—to sophisticated hacks that could threaten the integrity of our voting systems.

It’s impossible to guarantee with 100% certainty that election fraud won’t be attempted, or actually happen. But the collective goal must be to make such criminal activity—and that’s exactly what it is—exceedingly rare, easily detectable, and of minimal (or no) material consequence.

We can certainly do better. Indeed, just this week, U.S. Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson took an important step by officially designating the nation’s election systems as part of the nation’s “critical infrastructure.” The goal is to improve and upgrade these systems to better protect them from vulnerability to any kind of cyber attack, whether from foreign nations or domestic criminals.

But simply building stronger electronic walls around an outdated approach to voting isn’t the right answer, either. The existing “default” for American voters is asking them to travel to more than 100,000 polling places on or just before Election Day. These physical polling stations have become increasingly reliant on technology for such purposes as keeping track of registered voters—and millions of voters now cast ballots on software-enabled voting machines, where their votes are recorded and tallied electronically.

By keeping these traditional, ballot-dispensing polling places at the center of America’s election universe, tomorrow’s hackers will simply continue to focus on how they can “up their game” to find vulnerabilities. Fortunately, there’s a simple, far better approach that would address the genuine fears of citizens on both sides of the aisle. This approach would create an electoral system that’s less vulnerable to consequential fraud—while also significantly boosting voter turnout.

That solution: Abolish the traditional polling place.

This isn’t some weird election fantasy. In Colorado, Oregon, and Washington, voters are no longer required to physically connect with their ballots, either by traveling to a designated polling place or by applying (and qualifying) for an absentee ballot.

Instead, it’s the government obligation to connect citizens with their ballots by mailing them to all registered voters about two weeks before Election Day. In such “vote at home” systems, most voters fill them out at a kitchen or dining room table. They can mail their ballots back—a 49-cent stamp costs far less than a gallon of gas or bus fare—or deliver them personally to any one of hundreds of official and secure ballot drop sites, many of them accessible 24 hours a day and located strategically across their states—for example, inside or outside of schools, libraries, police and fire stations, and post offices.

Does a vote-at-home system prevent the possibility of fraud or other electoral mischief? Again, of course not. But what it does do—and better than many polling place-based systems—is significantly reduce the potential impact of any such efforts, however rare.

In a vote-at-home system, prior to a ballot being counted, a voter’s signature on the return envelope must be verified against voter registration card records. This reduces tampering. In the last 50 years, billions of absentee ballots have been mailed out in all 50 states. (Almost 60 million alone were mailed out total for the 2012 and 2016 presidential races.) Fraud, coercion, stolen ballots—real or even attempted—have been total non-issues, including in vote-at-home states. Besides, if one truly believed mailed-out ballots were inherently far riskier, wouldn’t there be a hue and cry to abolish absentee ballots, period?

But there’s an even stronger argument for dispensing with the fraud bogeyman.

Mail-based voting systems today are far less risky than many polling place elections, precisely because they distribute ballots (and electoral risk) in such a de-centralized way. To have any semblance of success, an organized fraud effort must involve hundreds—if not thousands—of separate acts. All would be individual felonies, and all must go undetected to have any chance of success.

To be sure, no electoral system—including one based on a vote-at-home approach—can prevent all potential fraud, much less its appearance. Nor should it try to. Electoral systems must balance the need for basic integrity safeguards—to minimize the odds of invalid ballots being counted and affecting an election result—with the importance of maximizing access to the extent practicable for citizens wishing to exercise their democratic franchise.

Nonetheless, it’s better than the risks inherent in polling place-based elections that increasingly rely on electronic voting machines and proprietary software systems to record and tally votes. Though also extremely difficult to pull off, a single software hack potentially affects thousands of votes. It’s the difference between “retail fraud” and “wholesale fraud.” As one county clerk once put it to me, “Ever wonder why no one bothers to counterfeit pennies? If you’re going to risk the jail time, $20s and $100s make a lot more sense.”

Finally, there’s the issue of recounts in close elections. Every paper ballot cast in vote-at-home states can be physically inspected and re-tallied. Contrast that to states where electronic voting machines are so outdated that paper records don’t exist, and where recounts would have to focus on lines of software code. In the absence of paper ballots that voters directly filled out, who can definitively prove the software code wasn’t tampered with prior to the recount?

Had Hillary Clinton narrowly won Wisconsin and Michigan, we’d likely still be fiercely arguing over whether Pennsylvania’s voting machines had been hacked. They’re one of the states where outdated technology allows no physical record of each voter’s intended choices. The legal issues that swirled around Florida in 2000 might look like child’s play.

In addition to offering greater safeguards against consequential election hacking, vote-at-home systems significantly boost voter turnout. In 2016, the 68.4% of eligible citizens in vote-at-home states cast ballots, vs. 60% nationally. Voter turnout in midterm elections rises even more dramatically. Based on Election Assistance Commission records, just 48% of the nation’s active registered voters cast ballots in 2014; compare that to 65% in the three vote-at-home states.

Embracing a “ballot delivery model” that relies on 18th-century technology—the U.S. Postal Service—may seem counterintuitive. But in terms of making American elections safer—not to mention more participatory—“back to the future” is exactly the right prescription.

Phil Keisling, former Oregon Secretary of State (1991-1999), is now director of the Center for Public Service at Portland State University.