A version of this story appeared in the Feb. 16, 1998 issue of Fortune.

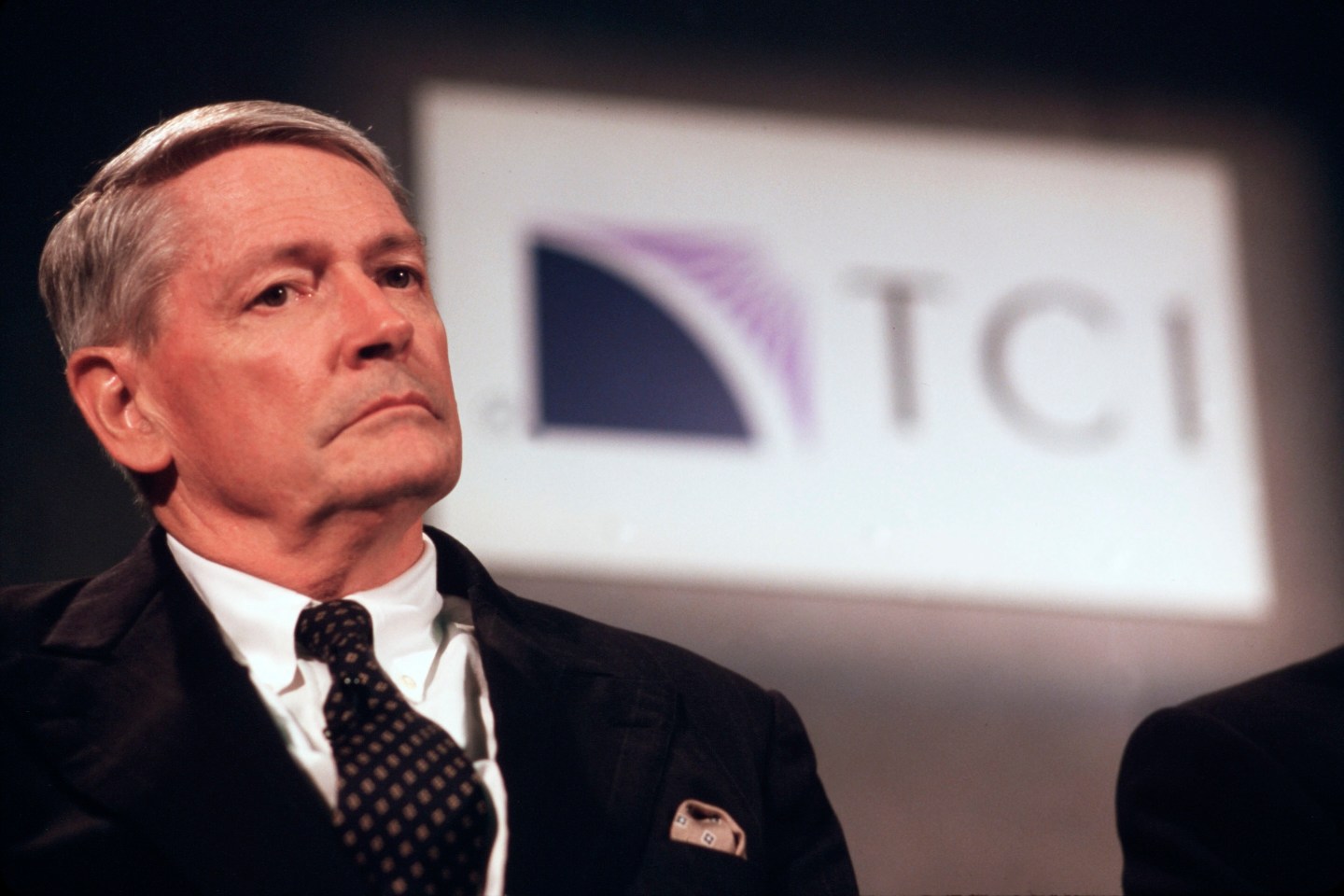

John Malone shows up for a 10 a.m. interview 15 minutes late. The CEO of cable giant TCI just got off the phone with Microsoft CEO Bill Gates. Actually he just got off the phone six times, because Gates was flying from Seattle to Houston, and the Airfone kept going dead. Malone explains with a lean, wolfish grin that a Microsoft negotiating team is holed up in another room he re at TCI’s Denver headquarters, hoping to complete a deal that would put Microsoft’s CE operating system into millions of gee-whiz set-top cable boxes TCI wants. So far, no dice.

The tension is building because seven hours ago, at 3 a.m., TCI signed an agreement with Microsoft’s archrival, Sun Microsystems, to include Sun’s Personal Java software in the boxes. Gates is “pretty agitated,” says Malone—a few hours from now, Bill-basher Scott McNealy, Sun’s CEO, is going to announce the deal at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. Gates is slated to hit the show’s podium tomorrow, and he doesn’t want to follow McNealy empty-handed. “Bill says that I am being unfair, being taken in by anti-Microsoft paranoia,” says Malone, smiling broadly. “But I told Bill, ‘Look, we just don’t have a deal yet.’ You know, it’s always a problem when you try to limit Microsoft to just a piece of things.”

Not many businessmen would even consider toying with Bill Gates, much less bragging about it. John Malone doesn’t give it a second thought. Once labeled the Darth Vader of cable, Malone got tough over 25 years of negotiating hundreds of deals with bankers, cable companies, regulators, and TV networks. Complex financial arrangements are second nature to him (just ask his shareholders); so is technology. Unlike Gates, a Harvard dropout, Malone has two master’s degrees—one in electrical engineering, the other in industrial management—and a Ph.D. in organizational theory. The former Bell Labs engineer took control of Tele-Communications Inc. in 1973, when it was a poky, $5-million-a-year company. He now heads up a three-headed conglomerate: Liberty Media, which holds programming assets like the Discovery Channel and Fox Sports and is also the largest shareholder in Time Warner (the parent of Fortune‘s publisher in 1998); TCI Ventures, which has investments in such companies as @Home and Sprint PCS and which just sold its stake in local phone company Teleport to AT&T; and TCI, a cable company with 14 million subscribers. The total market cap of the three companies is around $33 billion. After a recent settlement of his late partner Bob Magness’ estate, Malone’s stake is worth about $1.5 billion, and he controls 45% of the conglomerate’s voting stock.

Gates, of course, is worth $36 billion. Malone doesn’t care too much about that. The thing that irritates him is that Gates is Mr. Big on the digital playing field—the one place Malone knows nothing but defeat. In the early 1990s, Malone set out to be the Vanderbilt of the information highway, the entrepreneur who brought “convergence”—the fusion of video, interactive data, and telephone service over broadband pipes—into the homes of America. In 1992 he promised “500 channels.” They never materialized. In 1993 he tried to jump-start the revolution by merging TCI with Bell Atlantic. The deal cratered. Malone disappeared from the digital stage and from the public eye.

He’s back. Call him shameless, but once again Malone is preaching digital convergence. By this time next year, he says, TCI will offer a sophisticated digital cable connection that will probably include more than 100 digital video channels, features like E-mail, online bill paying, Web browsing, and impulse shopping (cubic zirconium with a click!); also, perhaps, telephone service over the Internet (see table below for more potential offerings). TCI, Time Warner, Comcast, and others have put in a “pretty firm” order for 15 million of the fancy set-top boxes customers will need to get the service. (TCI’s own minimum order is 5.9 million boxes.) Malone adds that he’ll spend $1.9 billion bringing TCI’s plant up to digital speed. “By the end of the year 2000,” he says flatly, sitting in his spacious 11th-floor office, “TCI’s plant will be capable of all this stuff, on a universal basis. I don’t think that I’ve ever been as excited about the future of this industry as I am right now. This could be really, really big.”

Silicon Valley agrees. The Internet craze has been a boon for computer and software companies, but they’re plagued by a scarcity of bandwidth. The Web has no hope of catching on as a consumer medium unless it can deliver instant gratification, not the world-wide wait. The panacea the techies now seek is a powerful set-top box—a computer, really—on top of every TV, delivering not just video but rocket-powered Internet access for everything from financial services to videophone conversations. The phone companies once promised to do the job but never delivered. Cable companies, however, are partway there. Last year customers of @Home and Time Warner’s Roadrunner service started getting the Net on PCs at blazing speeds via cable modems. “The interest the computer industry is showing in cable,” says cable analyst Paul Kagan, is “making the set-top box the most valuable square foot of real estate on earth.”

“I told Bill, ‘Look, we just don’t have a deal yet.’ You know, it’s always a problem when you try to limit Microsoft to just a piece of things.”

John Malone

That dawned on Malone last April, when he took a group of cable executives to Microsoft headquarters in Redmond, Wash. Just a week earlier Microsoft had bought WebTV, a Palo Alto startup that offered a way to browse the Web over TV. Gates explained that WebTV could revolutionize both TV and the Web, provided the cable industry could supply superfast connections. At dinner that night, Comcast President Brian Roberts joked that, given his enthusiasm, Gates should buy into the cable industry. Gates is nothing if not earnest; two months later he put $1 billion into Comcast, in return for an 11.6% stake.

Clearly, Silicon Valley wanted to dance. Malone, at heart more of a dealmaker than a cable operator, saw opportunity. Fire up the digital-convergence vision, order set-top boxes and system upgrades, and get Silicon Valley to foot as much of the bill as possible! At the least, this would help the industry increase revenues by selling a broader array of digital video. At best, interactive services would launch a new golden age for cable.

A less brazen CEO might have hesitated. TCI had stumbled badly after failing to merge with Bell Atlantic. Spending rose out of control, revenues stalled because of a rate freeze, customers complained about dismal service, and TCI lost business to satellite TV. In response Malone promised to “prick the bubble” of unrealistic expectations of futuristic services. He choked off investment, cutting the cable outfit’s capital expenditures in the first nine months of 1997 to $324 million, vs. $1.43 billion for the same period in 1996. At a trade show in 1996, he lectured fellow cable entrepreneurs “that this industry needs to structure itself so that it actually generates earnings.” This from a man who had said many times that cash flow is best used to fuel new growth. Earnings are for wusses.

Once he discovered Silicon Valley’s interest, Malone changed his tune and didn’t look back, not for a second. He insists that what he really meant in 1996 was that “the industry still had a way to go in terms of profitability. That doesn’t necessarily mean profits, but a higher return on invested capital in order to attract capital.” Huh? Despite the bout of fiscal restraint, TCI still has $15 billion of debt and a credit rating that hovers on the edge of investment grade. Yet Malone has undeniably boosted the company’s momentum. TCI added 125,000 subscribers last quarter. The end of a rate freeze allowed it to crank up subscription rates. Its share price has been up over $30, near its all-time high. And Malone is reinflating the visionary bubble as fast as he can.

Humility is of little use to someone who must both woo and ward off Bill Gates. Microsoft’s CEO, of course, would love to gain the same sort of lock on set-top boxes that he has on PCs. Last summer he told the cable companies he could guarantee delivery of a digital set-top box that would cost no more than $300. All they had to do was give Gates a cut of future revenues and let Microsoft design the system around its own software. Gates also dangled the possibility of additional large investments like the one he’d made in Comcast. Malone and the other cable operators Just Said No. Malone says that Gates wanted the industry to “give away too much of the future.” He adds, “I think that Microsoft’s many competitors had supplied everybody with plenty of anti-Microsoft, anti-Gates books.”

Malone and most of his fellow cable barons decided that the smart thing to do was to agree on a box that had open standards and bid out the components to keep the price down. That way, no one computer player could dominate. That way, Sun and Microsoft, say, would feud over who got into TCI’s box first. (Microsoft did clinch a deal to include Windows CE and elements of WebTV technology in the box—at 2 a.m. on the day Gates was scheduled to speak.) Next up are chipmakers like Intel and Fujitsu, which would like to supply the microprocessor the boxes require.

So far, then, Malone’s strategy for keeping Gates and the Valley at bay seems to be working. But TCI has a long, long way to go before it delivers anything approximating the interactive digital nirvana Malone promises. For one thing, TCI is not exactly outfitted for the digital future. Only 4% of its subscribers are reached by wires powerful enough to support the two-way communication needed for superfast interactive Web services. By comparison, close to half of Time Warner’s plant is adequately equipped. Malone says TCI will upgrade its plant over the next three years. After its fiscal trim job, TCI can generate the necessary cash flow.

Still more money will be needed to pay for set-top boxes. Malone explains that he is looking for partners—ranging from Microsoft to BankAmerica and TicketMaster—to underwrite them. The idea is that these companies will pay now in return for prominent positions in the system later. Let’s say you’re a TCI subscriber surfing the Net on your TV. When you click on an offer to buy a ticket, you might be directed to TicketMaster. If his plan succeeds, customers will not have to pay much more for this premium service. Unfortunately, new cable offerings don’t catch on quickly as a rule. Malone admits that only when there are millions of boxes out there will partners like banks, retailers, and advertisers clamor to provide interactive services. Analyst Spencer Grimes at Salomon Smith Barney says TCI could itself probably borrow enough money to pay for the boxes. But shareholders might blanch, given TCI’s already high debt.

Finally, Malone can’t feel entirely comfortable with his set-top-box supplier. General Instrument took four years—instead of the two it promised—to deliver the digital set-top box Malone ordered in 1993, during Convergence Mania, Part I. Some Silicon Valley insiders doubt that the firm can pull off the integration of so many components in the newest box. Says Malone: “Frankly, that’s why I picked Microsoft. All I want GI to do is slam WebTV’s technology and CE together with a set-top box and put in a bigger processor and more memory. I’m not asking them to invent anything.”

That kind of talk is a reminder that above all, John Malone is a pragmatic dealmaker. “I had a mentor named Moses Shapiro [former CEO of General Instrument],” he says, talking by phone one afternoon from his retreat in snowy Boothbay, Maine. His wife, Leslie, who imposes total privacy on their vacations, has stepped out to take some friends to the airport. “He told me, ‘Son, this is Talmudic wisdom. Always ask the question “If not?” Few people have good strategies for when their assumptions are wrong.’ That’s the best business advice I ever got.”

Any day now he and Leslie will drive to their other Maine home, deep in the wilderness near Quebec. The house sits at the end of a 14-mile-forest service road. Malone will drive the Chevrolet Suburban. But he’ll also have two snowmobiles on a trailer and snowshoes too. Just in case. He laughingly calls this “downside strategies in depth.”

So what’s his downside strategy if the digital vision falls short? He dials back some set-top-box orders and slows the rebuilding of TCI’s plant. In the meantime, Malone will at least be further along in providing digital video service—more cable modem service, more pay-per-view offerings, and, most important, more video channels. In other words, at worst he’ll have more sources of traditional revenue.

Malone will get whatever he can from this moment in the sun. TCI’s stock has a sheen it hasn’t had for years. That really intrigues Malone. His widely acknowledged genius, and his preferred occupation, is strategic maneuvering, the building and selling of assets. So it wouldn’t be a surprise to see him explore new deals. He’s reportedly in talks with AT&T, for example, over Ma Bell’s possibly making an investment in @Home. AT&T could conceivably offer local telephone service over the new set-top box.

Critics say Malone’s wheeling and dealing benefits the CEO more than other TCI shareholders. He argues, for instance, that getting voting rights transferred to himself from the estate of Bob Magness served TCI shareholders by keeping control of the company in-house rather than letting some outsider intervene. But some question whether he deserved a $150 million payment for giving TCI the right to buy his controlling stock under certain circumstances. Writes Sanford C. Bernstein analyst Tom Wolzien: “We shrug our shoulders and say this sort of deal historically has gone with TCI territory…and will continue to be tolerated by investors while the stock continues to perform well.”

For better or for worse, Malone sounds like a man ready to deal. He may not be ready to sell all of TCI. “[But] do I think it would make sense to break TCI into three, five, seven components if that were in the interest of the shareholder? You bet. If someone likes an arm or a leg better than we do, we’ll sell it,” he says. That’s the game, according to Malone. “Whether it’s Diller or Murdoch or whoever, if you can figure out a way to position your company to participate in other people’s great ideas, that’s the best of all worlds.” He might have mentioned Gates too, but then, that’s a given.

The Fortune Archives newsletter unearths the Fortune stories that have had a lasting impact on business and culture between 1930 and today. Subscribe to receive it for free in your inbox every Sunday morning.