Imagine for a moment that you know everything about next year’s Super Bowl. You know who will win, the score at the end of the first half, the MVP—you name it. That’s how Frank Johnson must feel at this time of year, because he always knows who’s going to win the Academy Awards long before anyone else does.

As head of the Century City, California, office of Price Waterhouse, Johnson is in charge of the firm’s tally of the votes cast by the members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for the year’s best movies, best actors, best visual effects, etc. At the end of this year’s ceremony, after 21 years, he’ll have to give up the most glamorous job in accounting, since he’s reached Waterhouse’s mandatory retirement age of 60. “It’s something I’ll really miss,” says Johnson. “It’s a lot of fun to read all the predictions about who’s going to win, and know that they’re wrong.”

There’s more to the job than smug certitude. (Or having movie stars throw money at you: In a 1988 rehearsal prank, Chevy Chase flashed a $1,000 bill at Johnson and asked him for the name of one of the winners.) Counting the ballots is a secretive, obsessive, squirrel-like drill fit for, well, an accountant.

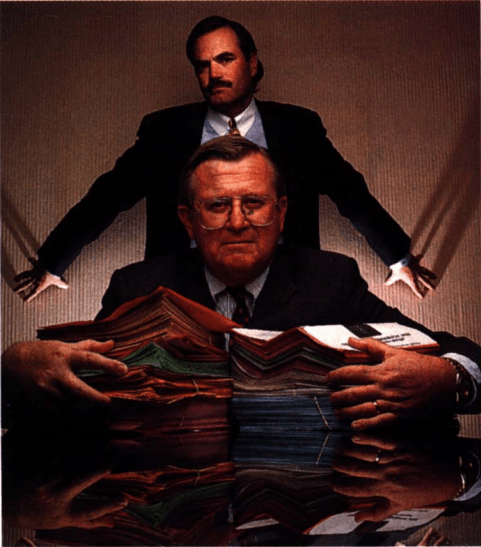

Here’s how it works: Completed ballots are returned by Academy members to Price Waterhouse in envelopes specially numbered to prevent forgery or duplication. As soon as the ballots arrive, they’re locked in a safe in the firm’s downtown Los Angeles office, known as “Fort Waterhouse.” Later the ballots are parceled out to the six Waterhouse employees assigned to do the actual counting. “We don’t use any computers to count the ballots,” explains Johnson. “Everything is still counted manually because it’s the only way to keep total security.” This means that it takes about a month to tally the votes in every category. During that time, the rules for counters are simple: Discuss the tally with anyone besides your supervisor, and you’re fired. The subtotals are then turned over to Johnson and his second in command, Waterhouse partner Greg Garrison (who will replace Johnson next year). Until this stage, no single individual has seen all the ballots, so no one knows who’s won or lost. Finally, Johnson and Garrison lock themselves in an office, total up the subtotals, and become the only two people in the entire world who know the winners of that year’s Academy Awards.

After Johnson and Garrison determine the winners, there’s still plenty of work to be done. Secretary Michelle Morgan types up cards with the name of every nominee, thereby ensuring that she doesn’t have a clue as to who the winners are. Then Johnson and Garrison prepare two sets of sealed envelopes containing the names of the winners. (Cards bearing the names of the losers are locked in Fort Waterhouse to prevent anyone from figuring out the winners by a process of elimination.) That way, if one of them gets stuck in traffic on the way to the ceremony, the other will—hopefully—still make it there in time.

But they’re still not done yet. Before they can go home and change into their tuxes, Johnson and Garrison have to memorize the names of the winners. This came in handy last year when Sharon Stone and Quincy Jones misplaced the envelope containing the name of the winner for best dramatic score. When Jones darted offstage in search of the envelope, Johnson told him that the winner was Il Postino (kind of ironic, isn’t it?) and spared everyone the extra embarrassment.

Waterhouse likes to boast about how it has never made a mistake in the 62 years that it has been determining winners for the Academy. However, it does admit it made a mistake at the 1990 Soul Train Music Awards, one of the other shows it handles, when the award for best urban contemporary single was mistakenly given to Karyn White instead of Janet Jackson when their two cards got stuck together. Waterhouse is, um, highly confident that this won’t happen at the Academy Awards, but you never know. Chances are, right before this year’s best picture is announced, the two guys who already know the winner are still going to be on the edge of their seats, just like you.

This article originally appeared in the March 31, 1997 issue of Fortune magazine.