One way or another, U.S. debt will stop expanding unsustainably, but the most likely outcome is also among the most painful, according to Jeffrey Frankel, a Harvard professor and former member of President Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers.

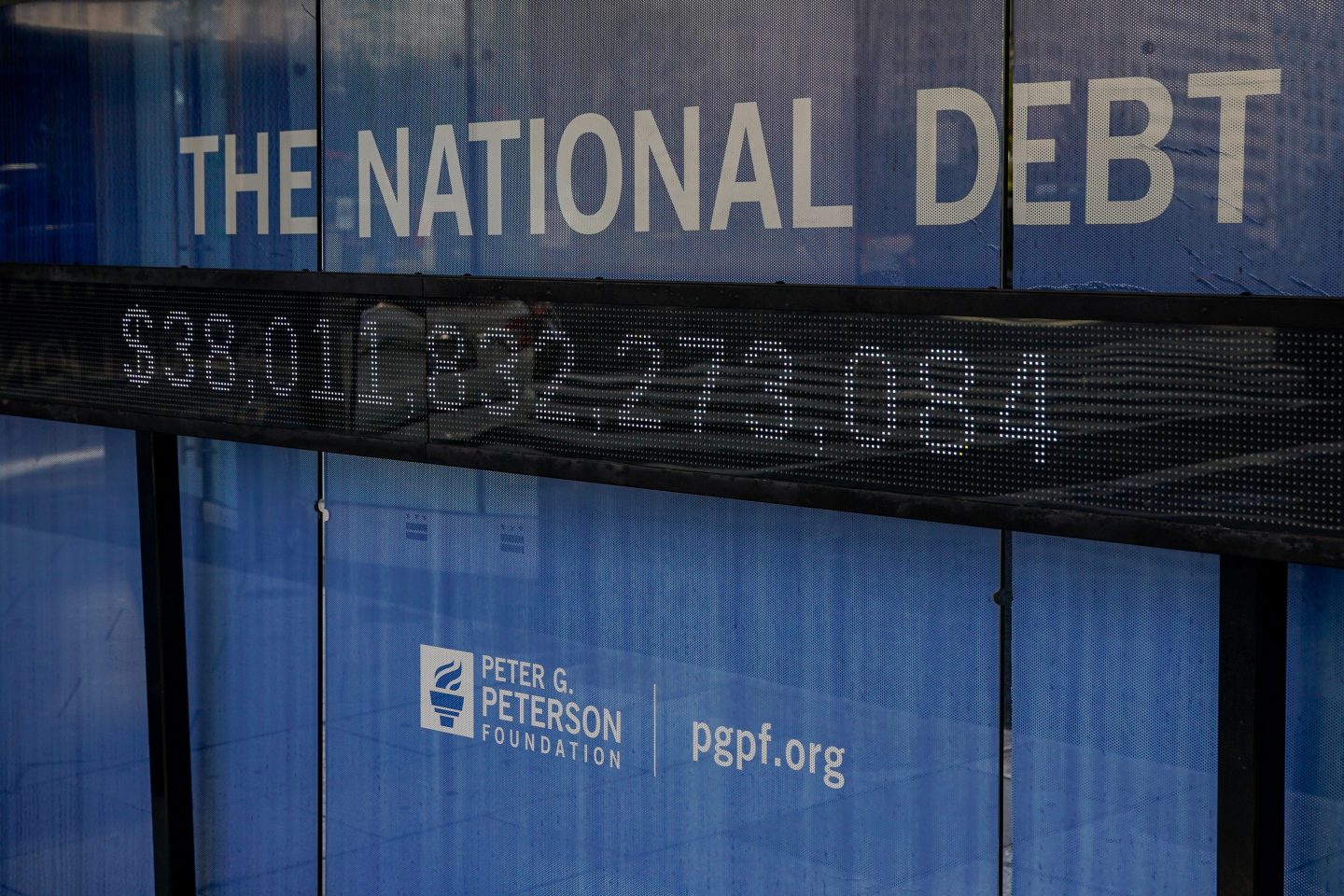

Publicly held debt is already at 99% of GDP and is on track to hit 107% by 2029, breaking the record set after the end of World War II. Debt service alone is more than $11 billion a week, or 15% of federal spending in the current fiscal year.

In a Project Syndicate op-ed last week, Frankel went down the list of possible debt solutions: faster economic growth, lower interest rates, default, inflation, financial repression, and fiscal austerity.

While faster growth is the most appealing option, it’s not coming to the rescue because of the shrinking labor force, he said. AI will boost productivity, but not as much as would be needed to rein in U.S. debt.

Frankel also said the previous era of low rates was a historic anomaly that’s not coming back, and default isn’t plausible given already-growing doubts about Treasury bonds as a safe asset, especially after President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariff shocker.

Relying on inflation to shrink the real value of U.S. debt would be just as bad as a default, and financial repression would require the federal government to essentially force banks to buy bonds with artificially low yields, he explained.

“There is one possibility left: severe fiscal austerity,” Frankel added.

How severe? A sustainable U.S. debt trajectory would entail elimination of nearly all defense spending or almost all nondefense discretionary outlays, he estimated.

For the foreseeable future, Democrats are unlikely to slash top programs, while Republicans are likely to use any fiscal breathing room to push for more tax cuts, Frankel said.

“Eventually, in the unforeseeable future, austerity may be the most likely of the six possible outcomes,” he warned. “Unfortunately, it will probably come only after a severe fiscal crisis. The longer it takes for that reckoning to arrive, the more radical the adjustment will need to be.”

The austerity forecast echoes an earlier note from Oxford Economics, which said the expected insolvency of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds by 2034 will serve as a catalyst for fiscal reform.

In Oxford’s view, lawmakers will seek to prevent a fiscal crisis in the form of a precipitous drop in demand for Treasury bonds, sending rates soaring.

But that’s only after lawmakers try to take the more politically expedient path by allowing Social Security and Medicare to tap general revenue that funds other parts of the federal government.

“However, unfavorable fiscal news of this sort could trigger a negative reaction in the U.S. bond market, which would view this as a capitulation on one of the last major political openings for reforms,” Bernard Yaros, lead U.S. economist at Oxford Economics, wrote. “A sharp upward repricing of the term premium for longer-dated bonds could force Congress back into a reform mindset.”