What’s so special about the number 2? Quite a lot, if you’re a central banker—and that number is followed by a percent sign.

That’s been the de facto or official target inflation rate for the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and many other similar institutions since at least the 1990s.

But in recent months, inflation in the U.S. and elsewhere has soared, forcing the Fed and its counterparts to jack up interest rates to bring it down to near their target level.

As an economist who has studied the movements of key economic indicators like inflation, I know that low and stable inflation is essential for a well-functioning economy. But why does the target have to be 2%? Why not 3%? Or even zero?

Soaring inflation

The U.S. inflation rate hit its 2022 peak in July at an annual rate of 9.1%. The last time consumer prices were rising this fast was back in 1981—over 40 years ago.

Since March 2022, the Fed has been actively trying to decrease inflation. In order to do this, the Fed has been hiking its benchmark borrowing rate—from effectively 0% back in March 2022 to the current range of 3.75% to 4%. And it’s expected to lift interest rates another 0.5 percentage point on Dec. 14 and even more in 2023.

Most economists agree that an inflation rate approaching 8% is too high, but what should it be? If rising prices are so terrible, why not shoot for zero inflation?

Maintaining stable prices

One of the Fed’s core mandates, alongside low unemployment, is maintaining stable prices.

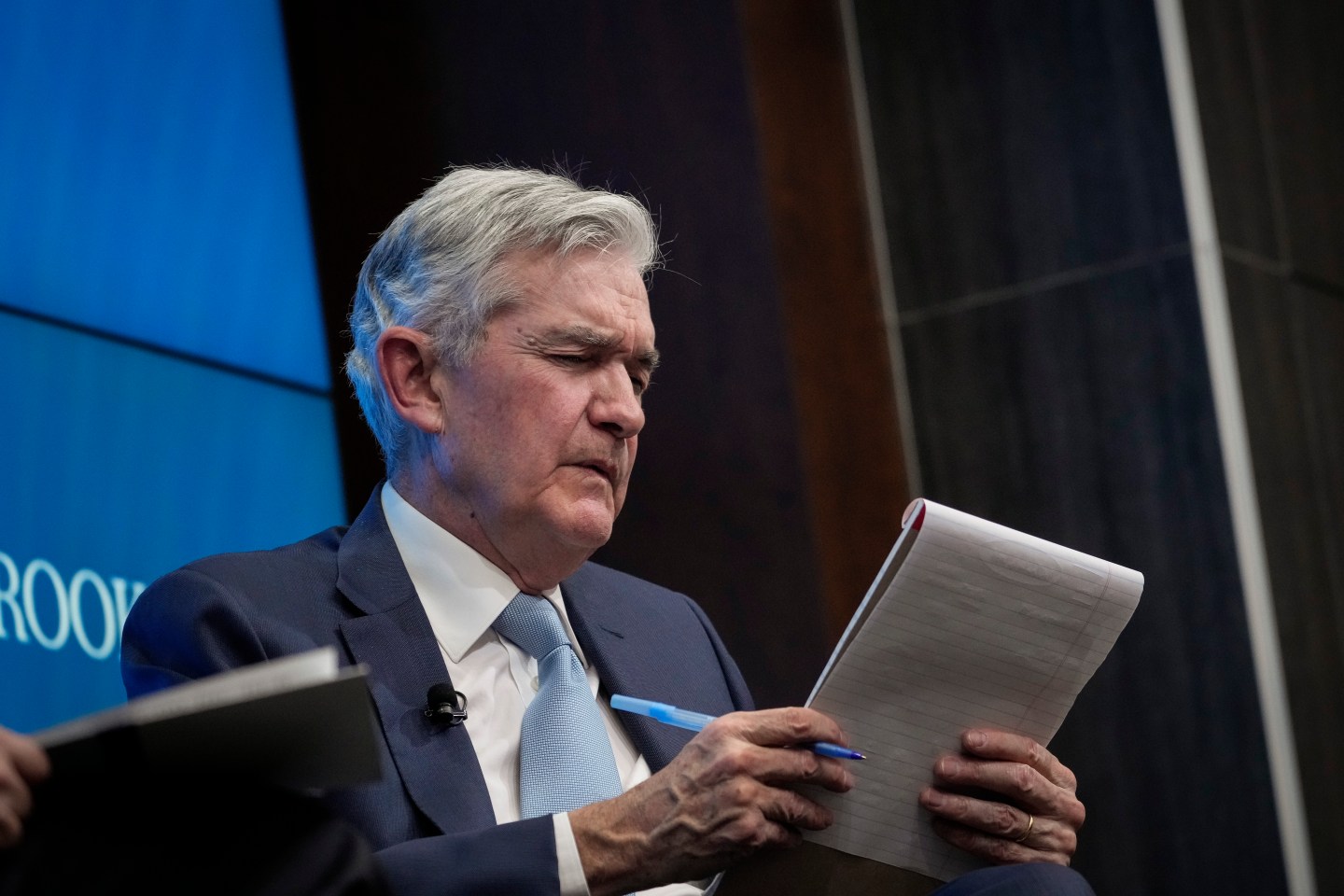

Since 1996, Fed policymakers have generally adopted the stance that their target for doing so was an inflation rate of around 2%. In January 2012, then-Chairman Ben Bernanke made this target official, and both of his successors, including current Chair Jerome Powell, have made clear that the Fed sees 2% as the appropriate desired rate of inflation.

Until very recently, though, the problem wasn’t that inflation was too high—it was that it was too low. That prompted Powell in 2020, when inflation was barely more than 1%, to call this a cause for concern and say the Fed would let it rise above 2%.

Many of you may find it counterintuitive that the Fed would want to push up inflation. But inflation that is persistently too low can pose serious risks to the economy.

These risks—namely sparking a deflationary spiral—are why central banks like the Fed would never want to adopt a 0% inflation target.

Perils of deflation

When the economy shrinks during a recession with a fall in gross domestic product, aggregate demand for all the things it produces falls as well. As a result, prices no longer rise and may even start to fall—a condition called deflation.

Deflation is the exact opposite of inflation—instead of prices rising over time, they are falling. At first, it would seem that falling and lower prices are a good thing—who wouldn’t want to buy the same thing at a lower price and see their purchasing power go up?

But deflation can actually be pretty devastating for the economy. When people feel prices are headed down—not just temporarily, like big sales over the holidays, but for weeks, months or even years—they actually delay purchases in the hopes that they can buy things for less at a later date.

For example, if you are thinking of buying a new car that currently costs US $60,000, during periods of deflation you realize that if you wait another month, you can buy this car for $55,000. As a result, you don’t buy the car today. But after a month, when the car is now for sale for $55,000, the same logic applies. Why buy a car today, when you can wait another month and buy a car for $50,000 next month.

This lower spending leads to less income for producers, which can lead to unemployment. In addition, businesses, too, delay spending since they expect prices to fall further. This negative feedback loop—the deflationary spiral—generates higher unemployment, even lower prices and even less spending.

In short, deflation leads to more deflation. Throughout most of U.S. history, periods of deflation usually go hand in hand with economic downturns.

Everything in moderation

So it’s pretty clear some inflation is probably necessary to avoid a deflation trap, but how much? Could it be 1%, 3% or even 4%?

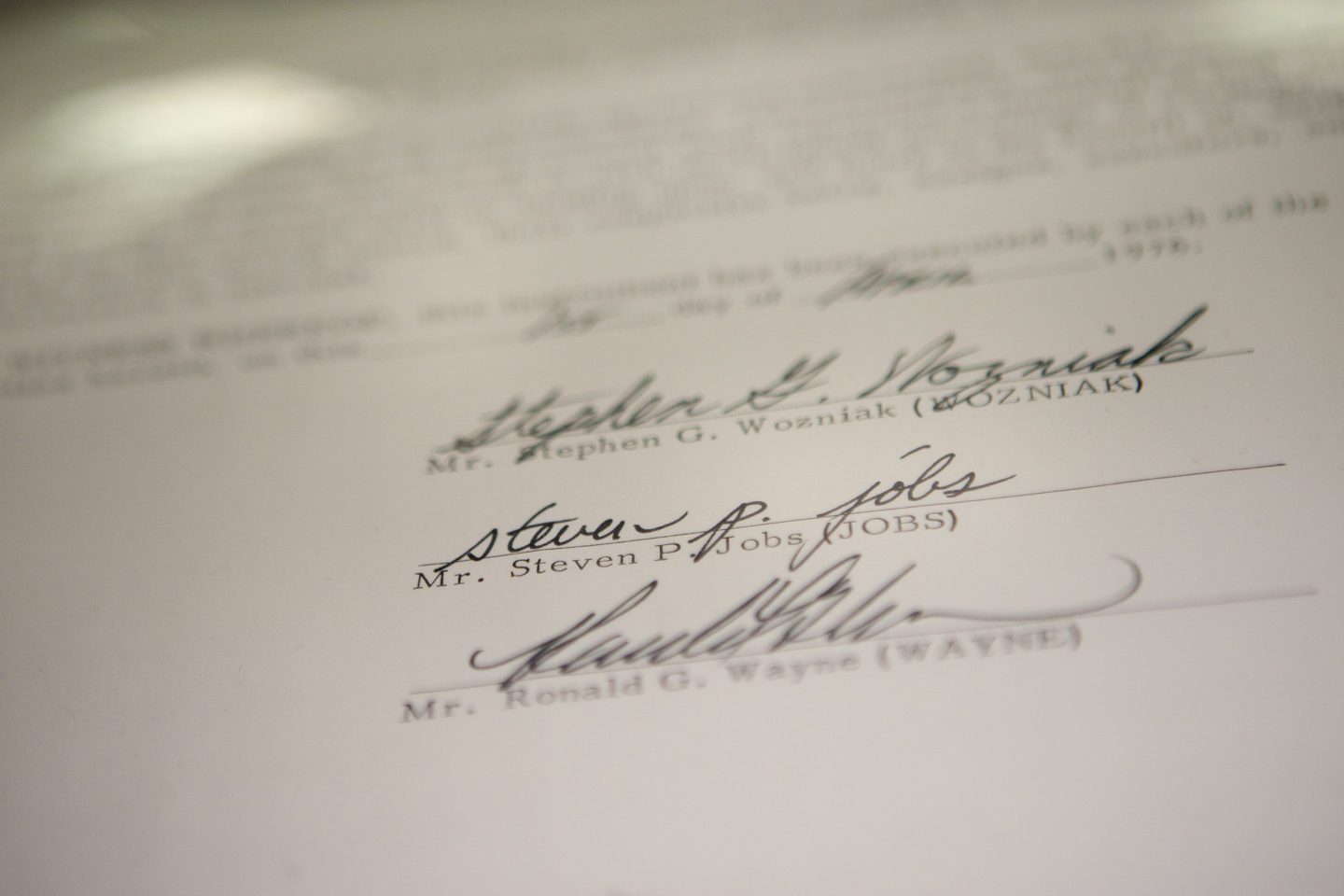

Maybe. There isn’t any strong theoretical or empirical evidence for an inflation target of exactly 2%. The figure’s origin is a bit murky, but some reports suggest it simply came from a casual remark made by the New Zealand finance minister back in the late 1980s during a TV interview.

Moreover, there’s concern that creating economic targets for economic indicators like inflation corrupts the usefulness of the metric. Charles Goodhart, an economist who worked for the Bank of England, created an eponymous law that states: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

Since a core mission of the Fed is price stability, the target is beside the point. The main thing is that the Fed guide the economy toward an inflation rate high enough to allow it room to lower interest rates if it needs to stimulate the economy but low enough that it doesn’t seriously erode consumer purchasing power.

Like with so many things, moderation is key.

Veronika Dolar, Assistant Professor of Economics, SUNY Old Westbury

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Our new weekly Impact Report newsletter examines how ESG news and trends are shaping the roles and responsibilities of today's executives. Subscribe here.