Most of the time, to get your hands on a Nobel Prize in economics, you need some serious brain power, decades of hard work on an esoteric subject, and the universal respect of the economics community. Now, to join the ranks of Krugman, Hayek, Myron and Scholes, all you need is a small fortune and the desire to spend it.

That’s right, this week, the Los Angeles-based auction house Nate D. Sanders will be accepting bids online for the Nobel Prize awarded to Belarusian-American economist Simon Kuznets, the third ever recipient of the Nobel Prize in economics. (If you are thinking about buying this piece, you should probably be aware that the economics prize is kind of the red-headed stepchild of the Nobel, as it was never endowed by Alfred Nobel himself, but by the Swedish Central Bank, decades after Nobel’s death).

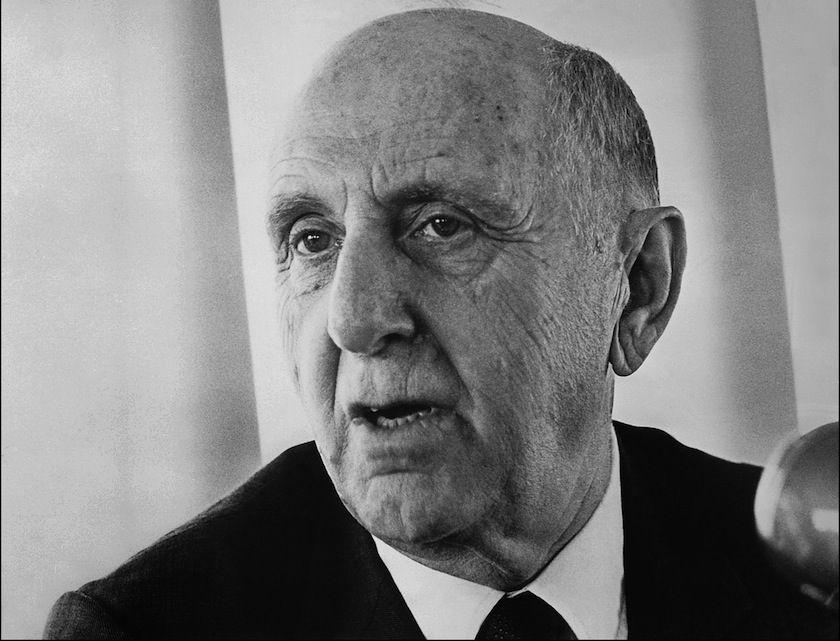

That said, if you’re gonna shell out $150,000 on a Nobel Prize in economics—that’s where bidding starts—allow me to humbly suggest that this be the one. While every Nobel Prize-winning economist has made a great contribution to the science of economics, you’d be hard pressed to find someone who has had a bigger impact on the world beyond economics than Simon Kuznets.

Kuznets, who died in 1985, is the grandfather of the concept of gross domestic product, a statistic that gets bandied about every day in the press, by politicians, and activists. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that, for some, GDP is the single best measure of human progress. The ubiquity of the statistic might lead some to think of it as timeless, but, in fact, it is quite young. The U.S. government only grew interested in calculating estimates of national income—of which GDP is one measure—during the depths of the Great Depression.

The idea of computing national income goes back to at least the 17th century. Private groups, like the National Bureau of Economic Research and the National Industrial Conference Board in the U.S., had been working to compute national income statistics in the United States in the years leading up to the Depression. But there was little agreement over what should be included in these measures. One bone of contention, for instance, was whether it should include household work, like child care or the preparation of meals.

Kuznets delivered his estimates to the Senate in 1934, putting numbers to the great suffering during those dark days. He showed that between 1929 and 1932 national income had fallen by more than 50%, and the income of wage earners had fallen 60%. These statistics helped guide the U.S. government’s efforts to stimulate the economy out of the Great Depression and the “recession within the depression” that struck the country in 1937.

Over the years, Kuznets and his colleagues tinkered with their methods, developing gross national product (GNP) in 1942, which measures the value of goods and services produced within the borders of the U.S. Unlike national income, GNP ignores the depreciation of capital stock. This was essential to understanding America’s war potential because it measured the production capability of the assets within our borders, regardless of whether foreigners owned those assets. The economics world gradually came to favor gross domestic product in the 1990s, partly as a reflection of the globalization of the U.S. economy. GDP, unlike GNP, measures the output of assets owned by U.S. citizens or entities that are both inside and outside the country.

Even today, there is a fierce debate over the worth of statistics like GDP. Some economists on the right side of the political spectrum question the wisdom of including government spending in our measures of national income because there is no market test for whether these expenditures do anything to improve welfare or make us richer. Those on the left criticize GDP for its failure to account for environmental degradation or the depletion of resources. If an oil company extracts $1 billion of oil from the ground and burns it, did we really become $1 billion richer? Or do we simply have less oil in the ground and more pollution?

The criticisms of GDP are numerous. In 2008, then French President Nicolas Sarkozy commissioned a group of economists, including Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, to devise a new measure of national wealth that would include measures of quality of life and the sustainability of wealth, rather than just raw production figures.

Despite the criticisms, it’s unlikely governments will revise how they measure economic progress in the near future because the proposed alternatives involve a most difficult question: what constitutes well being and wealth? Considering the U.S. government can’t even tackle an overhaul of its tax code, asking it to address these loftier questions is probably a bit much.

But the debate over GDP is testament to just how important it is. We need these numbers to help us understand economic progress. Policy makers in the early 20th century likely failed to react as effectively to the Great Depression as they could because they lacked such tools at their disposal. In an age when we’re drowning in big data and statistics, such a scenario is hard to imagine. So, if you’re a history buff or an econ nerd—and the kind of person who will spend six figures on a piece of memorabilia—take a look at Kuznet’s prize.