Although still private, the shadow of OpenAI and its still unprofitable business despite the blockbuster success of ChatGPT have rattled markets throughout the back half of 2025. Talk of a bubble in artificial intelligence has not been quelled despite Nvidia delivering yet another blockbuster quarter in November. The question remains of how OpenAI will balance ChatGPT’s seemingly endless desire, on the one hand, for “compute,” provided by data centers sprouting throughout the economy, with a business model that takes it from the red into the black. This is the same question that OpenAI CEO Sam Altman answered in a single exasperated word on a recent podcast appearance: “Enough.”

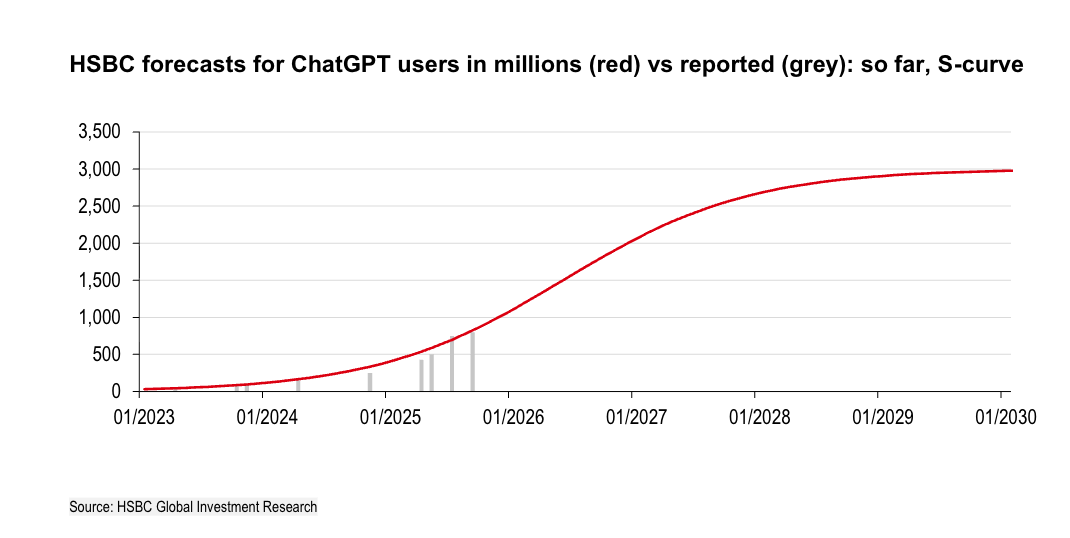

The investment bank HSBC, while clarifying that it still believes AI is a “megacycle” and that its forecasts “indicate a leading position for OpenAI from a revenue standpoint,” nevertheless calculates that the company faces an extraordinary financial mountain if it is to deliver on its ambitions. HSBC Global Investment Research projects that OpenAI still won’t be profitable by 2030, even though its consumer base will grow by that point to comprise some 44% of the world’s adult population (up from 10% in 2025). Beyond that, it will need at least another $207 billion of compute to keep up with its growth plans. This stark assessment reflects soaring infrastructure costs, heightened competition, and an AI market that is surging in demand and cash-intensive to a degree beyond any technology trend in history.

HSBC’s semiconductor analyst team, led by Nicolas Cote-Colisson, produced the figure by updating its OpenAI forecasts for the first time since mid-October, factoring in recent multiyear commitments to cloud computing, including a $250 billion agreement with Microsoft and a $38 billion deal with Amazon. More important, HSBC notes, these deals came without any new capital injection, and they are the latest in a series of capacity expansions that now see OpenAI aiming for 36 gigawatts of AI compute power by decade’s end. Assuming that one gigawatt can power roughly 750,000 homes, electricity on this scale would represent the needs of a state somewhat smaller than Texas and a little larger than Florida. The Financial Times’ Alphaville blog, which previously reported on HSBC’s forecast, described OpenAI as “a money pit with a website on top.”

HSBC projects that OpenAI’s cumulative free cash flow by 2030 will still be negative, leaving a $207 billion funding shortfall that must be filled through additional debt, equity, or more aggressive revenue generation. HSBC analysts model OpenAI’s cloud and AI infrastructure costs at $792 billion between late 2025 and 2030, with total compute commitments reaching $1.4 trillion by 2033 (HSBC notes that Altman has laid out a plan for $1.4 trillion in compute over the next eight years). It will have a $620 billion data-center rental bill alone.

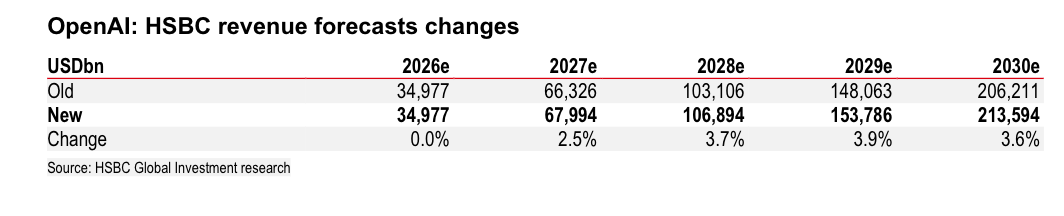

Despite this, projected revenues—though growing rapidly, to over $213 billion in 2030—would simply not be enough to bridge the divide. (The bank’s revenue projections are based on an assumption of a higher proportion of paid subscribers in the medium term and an assumption that large language model, or LLM, providers will capture some of the digital advertising market.)

The bank notes several options to close the gap, including dramatically ramping up the proportion of paid subscribers (going from 10% to 20% could add $194 billion in revenue); capturing a larger share of digital ad spending; or extracting extraordinary efficiencies from compute operations. But even under bullish conversion and monetization scenarios, the company would still need fresh capital beyond 2030.

OpenAI’s survival is closely tied to its financial backers and the AI ecosystem. Microsoft and Amazon are not only cloud providers but also major investors, and cloud players such as Oracle, Nvidia, and Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) all stand to gain—or lose—depending on OpenAI’s fortunes. The risks, however, are considerable: unproven revenue models; potential market saturation for AI subscriptions; the threat of regulatory scrutiny; and the sheer scale of necessary capital injections.

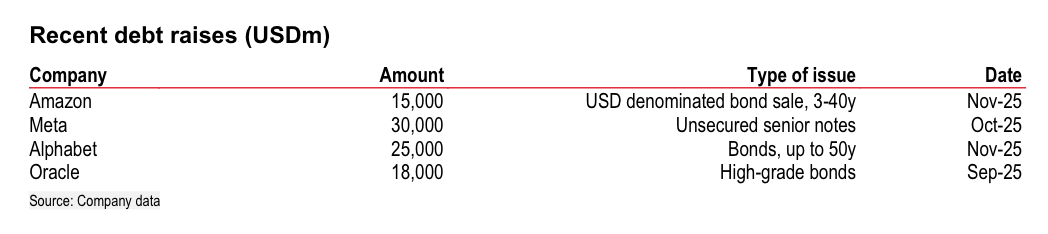

HSBC suggests that OpenAI could raise more debt to fund its compute requirements, but this would be “possibly the most challenging avenue in the current market conditions,” as Oracle and Meta have recently raised a “significant amount” of debt to finance AI-related capital expenditure, “raising market concerns about the general financing of AI.” The bank notes this is an exception as most of the so-called hyperscalers have funded themselves with free cash flow, as noted by JPMorgan’s Michael Cembalest recently. HSBC also noted a “sharp increase” in Oracle’s credit default swaps in recent days, which Morgan Stanley’s Lisa Shalett voiced alarm over several weeks earlier, in a previous interview with Fortune.

HSBC, like many other banks writing on the AI revolution, returned again to the famous quote by Nobel Prize winner Robert Solow that “you can see the computer age everywhere but in productivity statistics,” noting drily that “poor productivity gains driven by weak total factor (labor and capital) productivity are an unfortunate characteristic of today’s developed economies.” In fact, the bank notes that some aren’t convinced of a meaningful return yet from the 30-year-old internet revolution itself, citing Federal Reserve president John Williams’s 2017 comment that “productivity provided by modern technologies like the internet has so far only influenced our consumption of leisure—and hasn’t yet trickled down to offices or factories.”

Bank of America’s head of U.S. equity and quantitative strategy, Savita Subramanian told Fortune in August that she sees a “sea change” for productivity emerging out of the economy of the 2020s in ways that aren’t fundamentally about AI. Through a combination of factors, including post-pandemic wage inflation, she said that companies have been prompted “to do more with fewer people,” replacing people with process in a scalable and meaningful way. A consideration that was giving her pause, though, was a shift from an asset-light to an asset-heavier focus, as many of the most innovative tech companies have discovered a near-unquenchable thirst for a kind of hardware that carries a lot of risk with it: data centers.

A few months later, Harvard economist Jason Furman did a back-of-the-envelope calculation and found that without data centers, GDP growth would have been just 0.1% for the first half of 2025. OpenAI seems to be asking markets a question: Just how long can growth be built on the question of future returns—and a productivity revolution—from AI that are by no means ever guaranteed to arrive?