The holiday season is on a budget this year. American households are entering the next festive few weeks with constrained spending power, a result of weak real income growth and a softened labor market that is disproportionately affecting younger and lower-income workers, according to a comprehensive financial health report from the JPMorgan Chase Institute.

The analysis, which leverages anonymized financial data from Chase customers, suggests that the period of relying on pandemic-era excess cash liquidity is now “in the rearview mirror,” and many consumers are facing a spending season where budgets are “tempered by tepid income growth.” For consumers who are “relatively disadvantaged by high housing costs and hold less stock market wealth”—a group that disproportionately includes younger and lower-income individuals—they may have “just enough to spend, but not enough to splurge” this year.

These findings come at the end of a year when voter anger over the cost of living unseated Democrats from the White House and installed President Donald Trump for a second, nonconsecutive term, only to see voters back Democrats across the board in off-year elections. Many of the benefactors, including New York City Mayor–elect Zohran Mamdani, stressed the “affordability” problem that many are facing, while Trump’s approval ratings on the economy have plummeted.

Gen Z has born the brunt of what Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell memorably called a “low-hire, low-fire” labor market, where it’s looking pretty frozen. “Kids coming out of college and younger people, minorities, are having a hard time finding jobs,” Powell told reporters in September. Several weeks later, Goldman Sachs economists warned that “jobless growth” might become a permanent feature of the economy. Many economists have embraced a term from the Biden years that aligns with what JPMorgan is finding: “the K-shaped economy,” with diverging paths for wealthier and lower-income Americans.

To be sure, while JPMorgan’s report does not touch on the political scene and the affordability politics of 2025, it paints a picture of a tenuously balanced economic environment, full of friction with low real income and insufficient wealth accumulation among key demographics.

Real income stagnation mirrors recessionary period

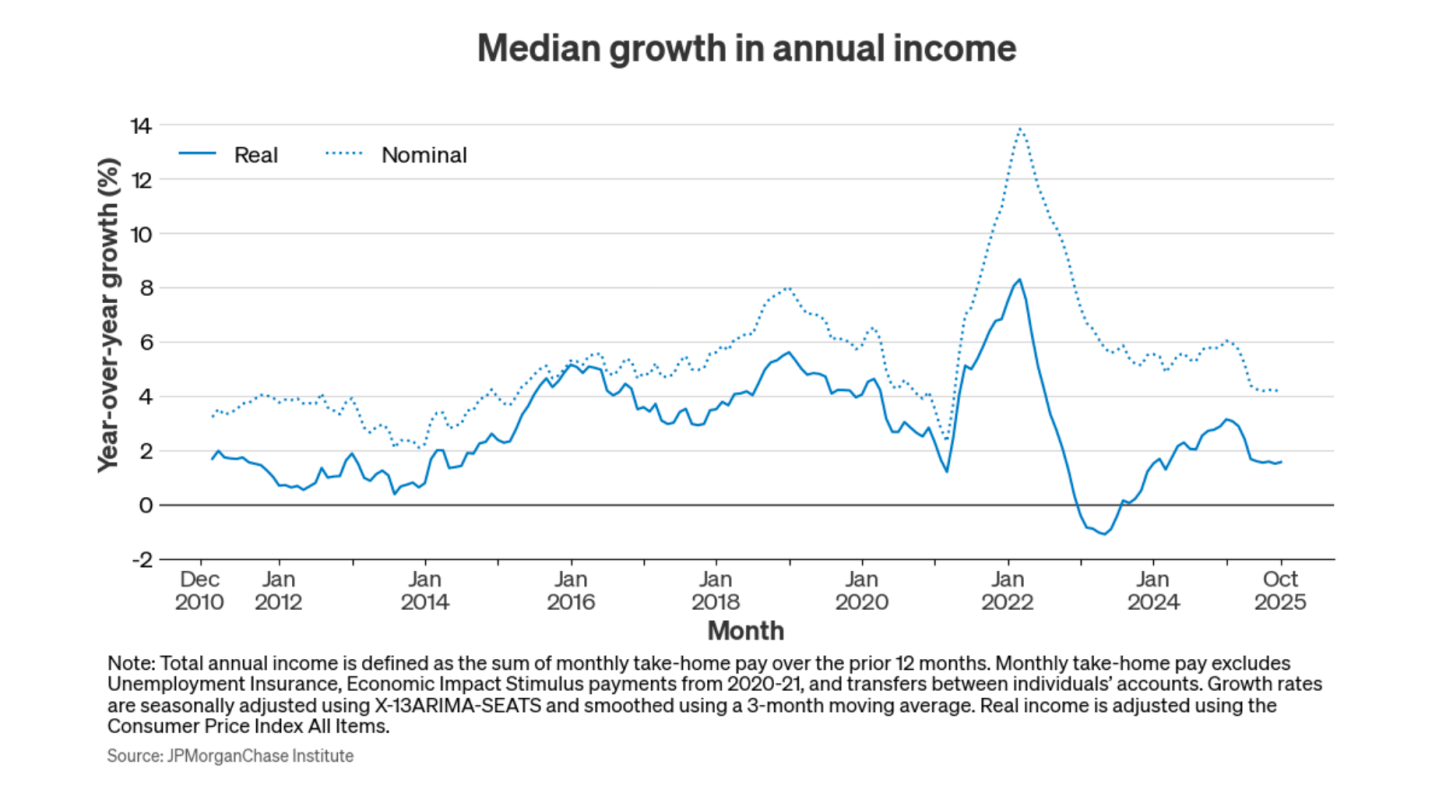

Median real income growth has sustained a weak trend for several months, with the October 2025 reading for prime-age individuals (ages 25–54) settling at only 1.6% in real terms. This low sustained pace is near the range observed during the weak labor market of the early 2010s, a period when the unemployment rate averaged 7%. This was, as the institute says, “when the unemployment rate was still elevated from the Great Recession,” although the current unemployment rate sits notably lower than in that period, at 4.3%.

While nominal income growth remains roughly consistent with pre-pandemic levels, the higher pace of consumer price increases means real purchasing power gains are low.

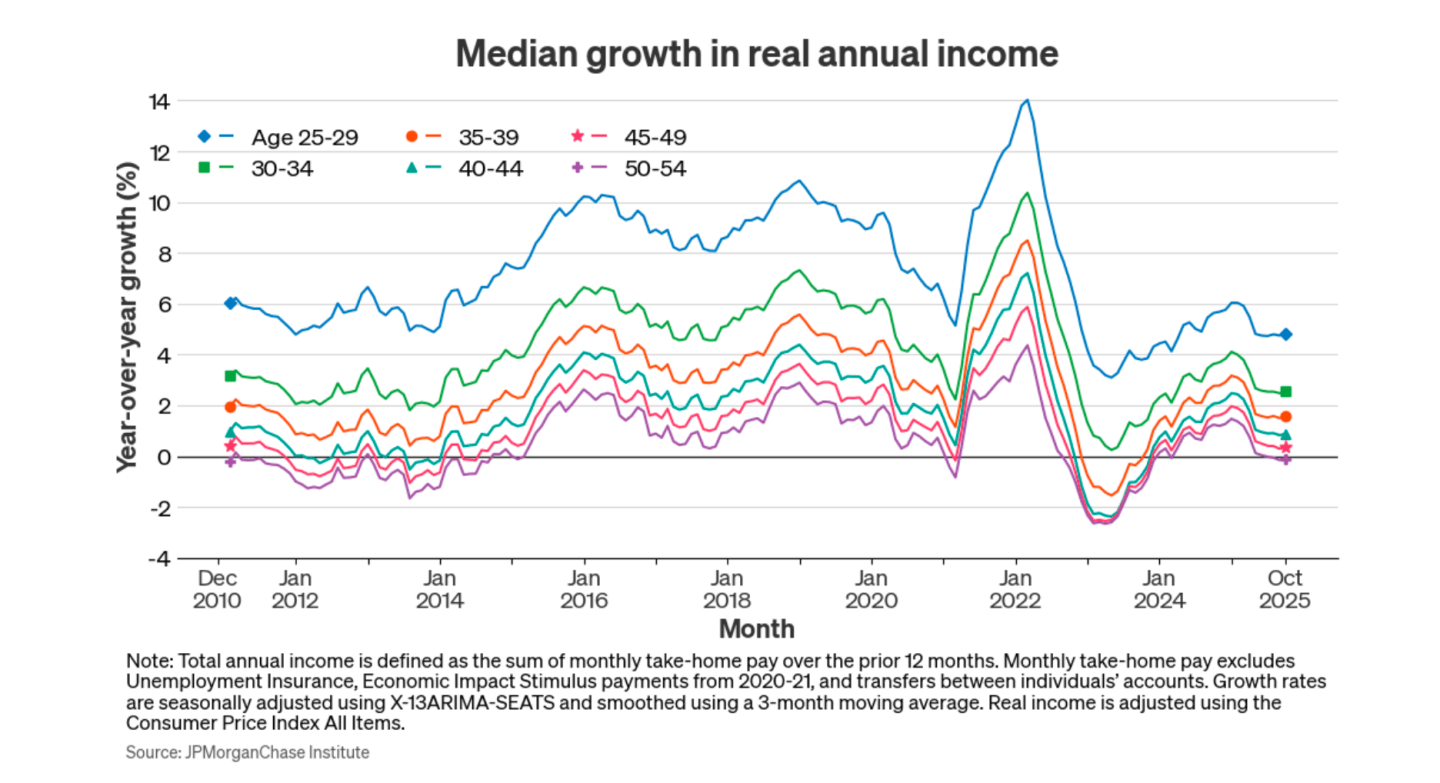

This general stagnation is proving particularly challenging across demographics. Young people “continue to underperform the typical early career growth pattern” as income growth for individuals ages 25–29 is currently below historical trends for younger workers. Younger workers typically rely on job switching to rapidly advance their careers. However, the current slowdown in hiring is hindering this typical rapid pace of income advancement.

The downturn in overall income growth is also impacting older demographics. Workers ages 50–54 are now experiencing negative real year-over-year income growth. And since older workers generally face slower annual gains, a combination of weakening in the labor market and an uptick in inflation can more easily send their purchasing power into negative territory. Negative real growth for older workers can lead to challenging adjustments, particularly for lower-wealth individuals who have not benefited from years of strong gains in housing and stock prices.

Flat balances offer little cushion

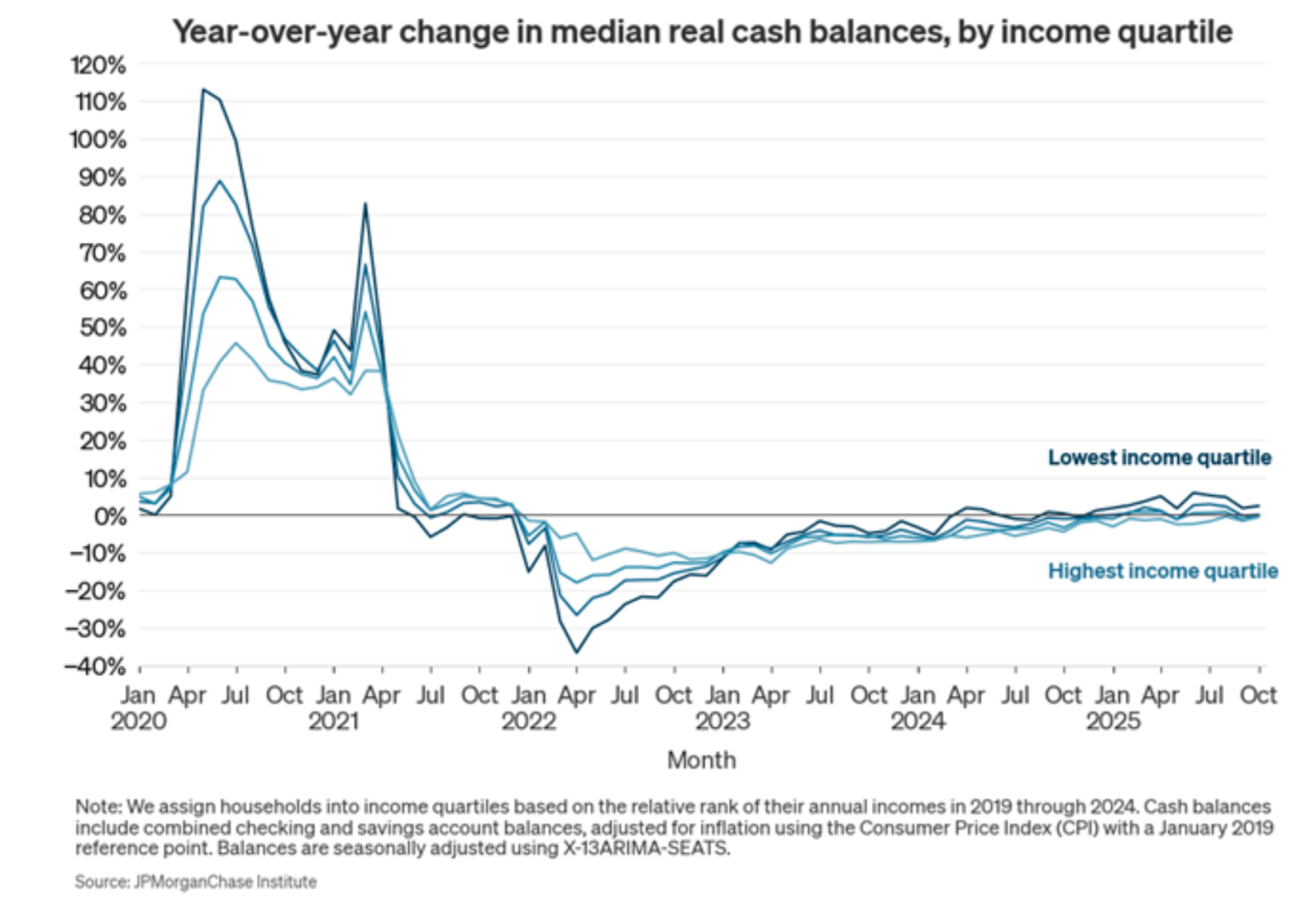

Households’ median real cash balances have remained flat since early 2024, holding steady throughout most of 2025. This stability marks a deviation from pre-pandemic trends, where real balances typically grew steadily at an annual rate of just over 6% as households aged. If balances had grown at that historical rate since 2020, they would be up 40% in October relative to 2019; instead, they are only up 23%.

This flat growth indicates that households are not accumulating additional cash reserves in their checking and savings accounts.

Although high-income households have continued to see slight declines in their bank balances (only 2% negative in October 2025), potentially owing to transfers to higher-yield accounts or investment brokerage accounts, low-income households returned to positive year-over-year bank balance growth in September 2024. Despite these shifts in savings strategy, the approximation of total cash reserves—including investment transfers—shows that growth has been positive for all income groups for at least the past year.

Going into the end of the year, consumers with constrained budgets may look to stock market gains to augment spending. However, the report cautions that these stock market gains are “highly unequally distributed,” leaving younger and lower-income groups with less of a financial cushion as they navigate stagnant real purchasing power.

For this story, Fortune used generative AI to help with an initial draft. An editor verified the accuracy of the information before publishing.