The following is an excerpt from Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates’ new book SOURCE CODE: My Beginnings.

When he wasn’t working, Paul lived in his magazines, his apartment littered with back issues of Popular Electronics, Datamation, Radio-Electronics, and spec sheets for all sorts of computers and their components. He could easily spend an hour foraging through Out of Town News, the landmark newspaper and magazine kiosk in the center of Harvard Square. From his growing pile of paper and publications sprang many ideas for any number of ventures Paul pitched me that fall.

Most of them centered on the microprocessor. For a while, Paul was set on the idea of building a computer company in the model of DEC. DEC had exploited new technologies to lower the price of computers and greatly expand their use. Could we do the same with inexpensive microprocessors, maybe string together multiple chips to make a superpowerful computer really cheaply? What about setting up a timesharing service aimed at consumers? People could dial into our computer to access news and other useful information, like, I don’t know, recipes?

We’d sift through these ideas over pizza or at Aku Aku, a Trader Vic’s–style Polynesian place, talking for hours as I sipped Shirley Temples (at 20 years old I was over the drinking age but preferred the kid’s mocktail to alcohol). Because of Paul’s love of computer hardware, his ideas often centered on building some kind of innovative computer. One great idea he came up with was a technique for wiring together cheaper, less-capable chips into a single powerful processor called a bit-slice computer. His question: Could we use this bit-slice technique to undercut IBM just as DEC had done a decade earlier? At the time, an industry-leading IBM System/360 mainframe computer could cost several hundred thousand dollars. I spent some time on my own studying the details of the IBM machine and Paul’s bit-slice idea. On our next night out, I told him I thought it could work. We could probably make a computer for $20,000 that would be equivalent to the 360.

Still, he knew that I was increasingly cooling to the idea of building hardware. The business of manufacturing computers seemed too risky to me. We’d have to buy parts, hire people to assemble the machines, and find lots of space to pull it off. And how would we ever realistically compete with big companies like IBM?

My view was informed by Traf-O-Data. For eighteen months our partner back in Seattle, Paul Gilbert, had been struggling to get our computer to work. The machine required the delicate coordination of electronic pulses that had to reach each of the machine’s memory chips at exactly the same moment. A delay of a microsecond and everything froze. One wire, a hair longer than it should be, or a trace amount of radiation it produced could throw off the pulses. And did, over and over. These endless glitches fed my worries that we were wasting our time, courting a life of tedious problem-solving that seemed hit-or-miss, not fully in our control.

Gilbert was a self-declared perfectionist, a math-obsessive engineer who doggedly stuck with a problem until he solved it. “I don’t like to be defeated. I’ll get it fixed regardless of what it takes,” he would say. (His girlfriend dropped him that year because he spent too much time on Traf-O-Data.)

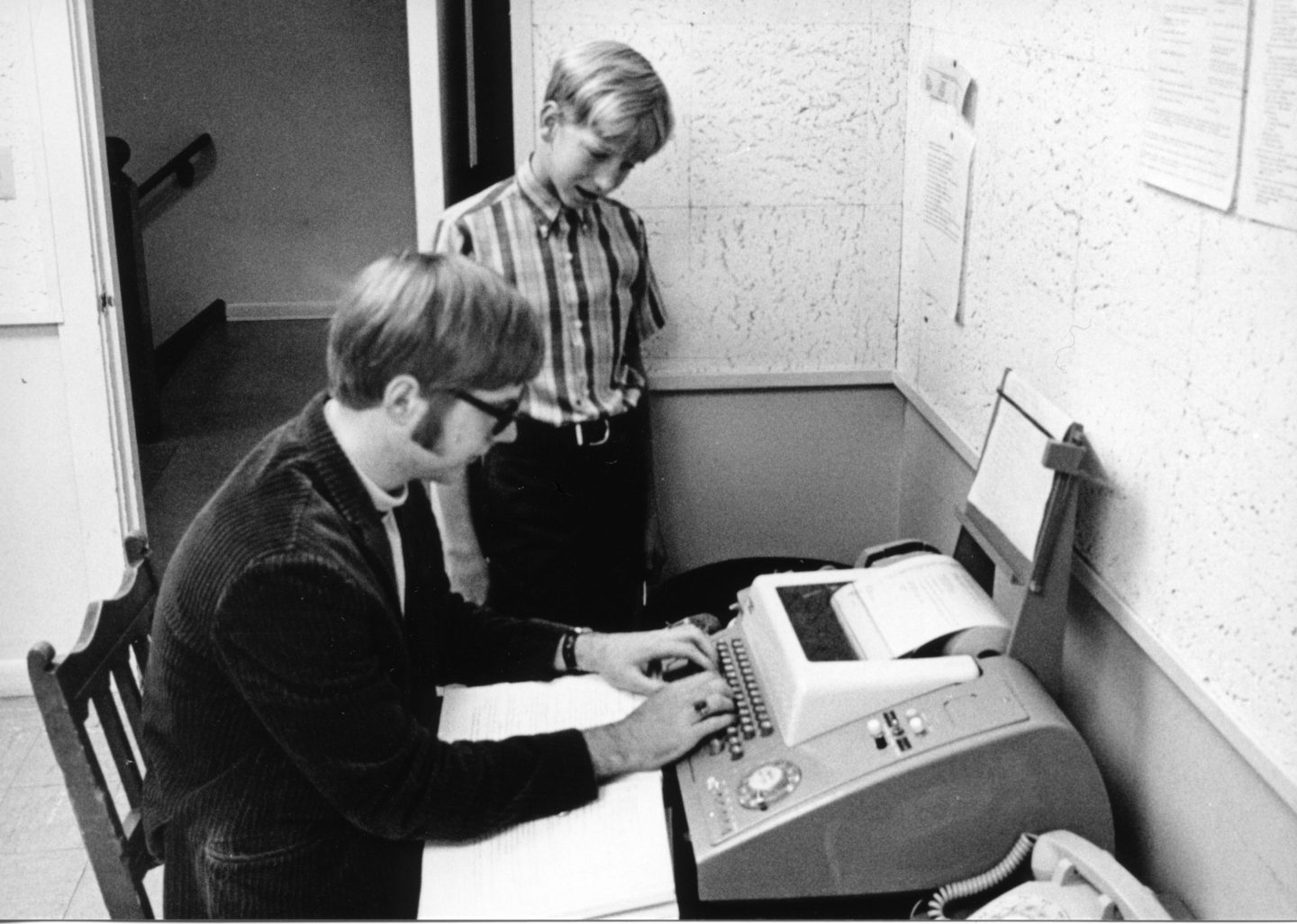

I wrote memory test software and then the two Pauls dove in. They’d stare at the oscilloscope patiently making the diagnosis: “a glitch in the data to the line on chip seven.” Kind of like those organic chemistry modules, there was a level of disorder to the hardware problems that frustrated me. I’m sure my nervous energy added to the stress. I was always pushing to see if there was something we could change or add to speed things up.

Gilbert eventually got the hardware working in the spring of my first year of college. That summer I arranged a meeting at my parents’ house with potential customers from Seattle’s King County. I had everything set perfectly that morning, but when the time came for my demo, the unit’s tape reader broke. I pleaded with my mom to tell them that it really, truly had worked flawlessly the night before. Our guests politely finished their coffee and left. After that, we laid out $2,000 for what we considered to be the Rolls-Royce of tape readers. All this effort and expense for a simple computer, with a single job of translating holes in a paper tape into graphs.

Again and again, my dinner conversations with Paul led back to software. Software was different. No wires, no factories. Writing software was just brainpower and time; the two of us sitting at a computer with full control over the output. And it’s what we knew how to do, what made us unique. It was where we had an advantage. We could even lead the way.

From the book SOURCE CODE: My Beginnings by Bill Gates, published on February 4, 2025, by The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Bill Gates.

Read more:

- Microsoft turns 50: How it’s remained essential, based on my 27 years there

- Satya Nadella has made Microsoft 10 times more valuable in his decade as CEO. Can he stay ahead in the AI age?

- Microsoft turns 50 as the world’s second largest company—trying not to fall behind on AI

- Microsoft’s memorable cultural legacies at 50, from Clippy to the Blue Screen of Death