The following excerpt, from Judah Taub’s new book How to Move Up When the Only Way Is Down, offers a fresh perspective on how a startup called Netflix crushed the once-dominant Blockbuster.

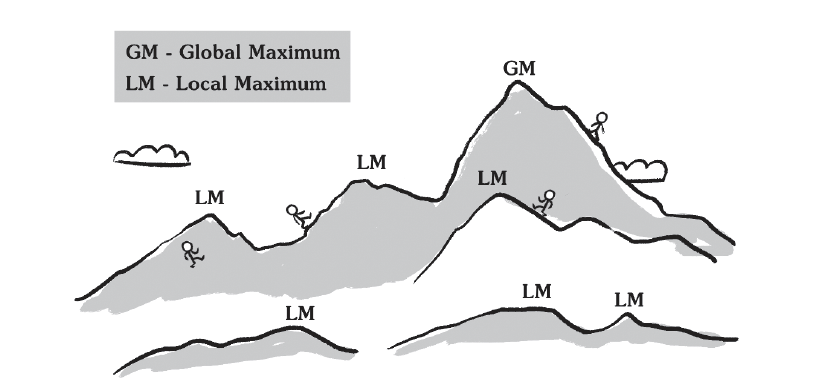

A Local Maximum is a point on a field that is not the highest or the best, but it is a point from which we can only go down (see the illustration below). It’s deceptive because it’s attractive. We are naturally pulled toward it and work very hard to get there, but once we arrive, we realize there is a higher or better option.

The Local Maximum scenario is one that affects us all, and in the most important aspects of our lives. As individuals, as managers, or as leaders, we devote our days, our skills, and our resources to pursuing particular goals. Yet, we are often blind as to whether a better, perhaps vastly better, course of action is available. We are so busy exercising our muscles to improve the speed and efficiency of our climb. But how effective are we at recognizing whether we are climbing the right peak in the first place, or in getting off the wrong peak to course correct while there is still time?

Business decisions

Most decisions include an element of Local Maximum, and the more complex the decision, the stronger the effects and dangers of a Local Maximum. This concept can apply to decisions that have small effects, such as which ice cream flavor to choose or which shoes to buy, and to decisions that have very large effects, such as which job to pursue, how to help people out of extreme poverty, how to build a company’s business roadmap, or even how to reach a carbon neutral society. The concept of Local Maximum offers new ways of thinking about human challenges as well as ways to avoid or address those problems, whether it’s global warming or what to order for breakfast.

My work with startups and various other life experiences with Local Maximums has helped me to understand we are all in the desert on our personal or corporate journeys trying to navigate our way to the highest mountaintop. Many times, we know we are not climbing the right mountain, but we are concerned about the costs of going back down. Other times, we may not be aware there is a much better mountain right around the corner. We need to understand our terrain to navigate it most effectively.

Blockbuster vs. Netflix

It was the year 2000, when Netflix CEO Marc Randolph and co-founder Reed Hastings chartered a private plane from California to Dallas, Texas, to meet with Blockbuster’s CEO, John Antioco. It took months to arrange a meeting, but it was finally confirmed at the last minute. Famously, the Netflix co-founders flew in after an alcohol-fueled company retreat, wearing shorts and flipflops, to present a merger proposal for Blockbuster to acquire their fledgling startup. The asking price was $50 million. As we all know, the deal never materialized. In his book, That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea, Randolph recalls the disastrous meeting, where Antioco essentially had to choke back his laughter in the face of the proposal. Acquiring Netflix made zero sense to Blockbuster. Following a merger deal with Viacom, the company was worth $8.4 billion and had been crowned the undisputed “King of the Video Rental Industry.”

But the laughter quickly died down. Although there was nothing Blockbuster couldn’t replicate in Netflix’s model (and they likely ended up spending 10 times more on advertising, content, user interface, and other costs), Netflix is now a now a noun and a verb worth over $300 billion, and Blockbuster went bust. Remarkably, even in 2008, only two years before filing for bankruptcy, Blockbuster’s Antioco said, “I’ve been frankly confused by this fascination that everybody has with Netflix…Netflix doesn’t really have or do anything that we can’t or don’t already do ourselves.”

The Blockbuster vs. Netflix tale is an eye-opening example of the powerful effect of a Local Maximum. Blockbuster had everything going for it: a global reach of contracts with the leading content producers plus a 28-day exclusivity over any competitor, a huge network of stores across all 50 states, deep pockets of capital, and a strong brand. Importantly, as Blockbuster executives said multiple times throughout their sparring history, there was nothing Netflix did or invented that Blockbuster could not replicate easily. There was no impregnable IP, technology, or secret Coca-Cola ingredient.

Beyond strategy

If you Google “why Blockbuster failed,” you are likely to get a blend of tactical errors such as the company’s obsession with late fees (which accounted for more than 15% of its revenue), poor customer service, and inattention to customer preferences. If you read one of the Ivy League case studies on the topic you will hear of the strategic errors, executional mistakes, and closed-minded senior management. The company’s documented errors certainly contributed to Blockbuster’s historic failure, but what if there is something deeper? What if it was already clear by 2000 that Netflix would be the obvious winner, Blockbuster was near its peak, and its senior management had to get everything right to survive rather than just not go wrong?

Blockbuster had everything Netflix had; it actually had even more. It had 9,000 physical stores and 65 million registered customers. It had 84,000 employees and was owed millions of dollars in late payment fees. Did these assets equate to a true advantage? As long as the target didn’t change, and the goal was to become the largest DVD rental company, yes. They helped the company climb the DVD mountain and provided a muscle moat to defend its business as well. But once it became clear the DVD mountain was limited, and there was a much better “online streaming mountain,” all of Blockbuster’s muscle became a hindrance. It made climbing down increasingly more difficult.

Mere months before filing for bankruptcy, Fast Company interviewed Blockbuster’s Head of Digital Strategy, Kevin Lewis. Trying to boost confidence around the company’s potential, he said, “Never in my wildest dreams would I have aimed this high.” I believe he was being honest, but when your Digital Strategy Officer cannot envision higher heights, you are probably climbing the wrong mountain.

Adapted with permission by the publisher, Wiley, from How to Move Up When the Only Way Is Down: Lessons from Artificial Intelligence for Overcoming Your Local Maximum by Judah Taub. Copyright © 2025 by Judah Taub. All rights reserved.