This piece originally appeared on Darden Ideas to Action.

Because they spur the creation of jobs, IPOs have historically been important drivers of growth for the U.S. economy. But in the mid-2000s, going public lost some of its luster. The earlier dot-com correction, Enron collapse and wave of corporate financial scandals triggered a regulatory cascade of new protections, which imposed more stringent standards on public companies. Small company IPOs declined precipitously in the U.S.; some American companies even chose to list on financial markets abroad, rather than at home.

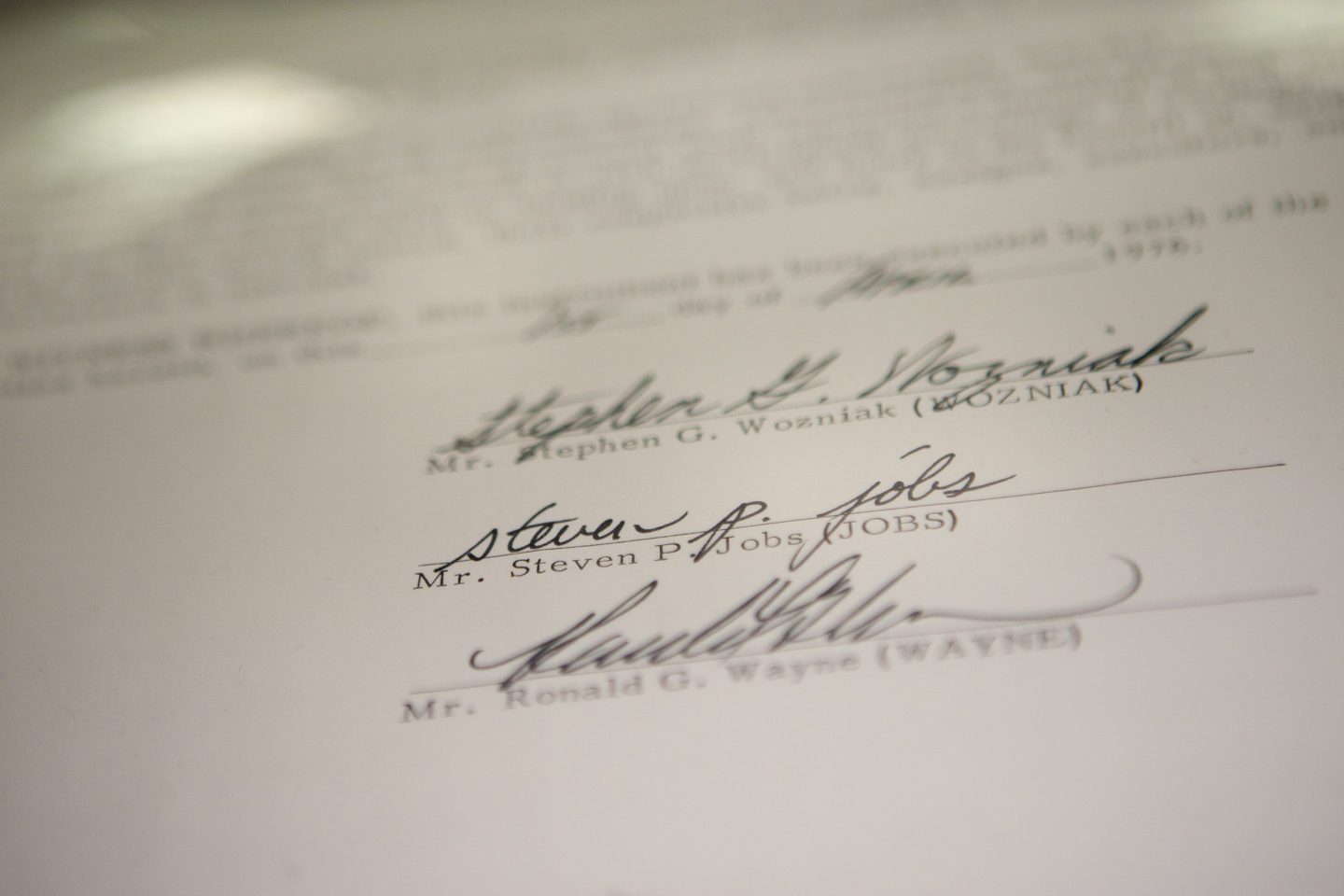

In 2012, concerned about the downtrend, Congress passed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act. With its bipartisan support and a politically catchy name — the “JOBS Act” — the legislation aimed to reduce the costs of going public and provide “on ramps” whereby newly public firms could gradually adjust to the higher reporting and governance standards of being a public company.

“IPOs have always been an important means for emerging companies to access capital. When you look at the evidence of how jobs are added in the U.S., it’s companies that go public. In the first five to 10 years, they add considerably to employment,” notes Susan Chaplinsky, Darden’s Tipton R. Snavely Professor of Business Administration. With colleagues from Lehigh University and the University of Colorado, Chaplinsky studied the JOBS Act’s impact in its first three years as law. The team analyzed more than 300 IPO prospectuses, filed from April 2012 through April 2015.

So has JOBS worked as intended? Chaplinsky says that her research — which she emphasizes is a first look at the Act — shows a mixed picture. Many of the intended benefits, such as increased IPO volume and lower costs, have not conclusively materialized. Yet some of the “de-risking” provisions aimed at reducing the uncertainty of the IPO process have been favorable to issuers.

The JOBS Act aims to reduce the costs of going public and the ongoing compliance costs of being a public company for the first five years a company is public. Issuers qualify for the Act if they are “emerging growth companies” (EGCs), which have less than $1 billion in revenue in their last fiscal year. Because of the high revenue cutoff, the vast majority of IPO issuers can qualify for the Act. EGCs can opt to report two years, rather than three years, of audited financial statements. They can also choose to provide limited information on top executives’ compensation. Post-IPO issuers can delay compliance with Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd Frank governance requirements. In theory, firms that opt for these “reduced disclosure” options have less information to compile and hence should spend less on legal, accounting and underwriting services.

But in reality, when Chaplinsky compared average costs for issuers before and after the Act’s passage, she “didn’t find any evidence that the JOBS Act reduced the direct costs of issue [underwriting, accounting, and legal fees].” Nor did companies seem to move through the IPO preparatory phase any faster — the number of days spent in registration stayed consistent.

In addition, Chaplinsky found evidence that when companies opted to disclose less, their indirect costs actually rose. “Issuers left more money on the table, through greater underpricing of shares,” Chaplinsky says. “It shows that investors value transparency and have some skepticism about reduced disclosure.”

In other words, companies that opted to disclose less information didn’t save on the direct costs of issue and paid a higher cost of capital through greater underpricing.

So what about the JOBS Act’s other major goal: to reduce risk for the issuer? Here Chaplinsky believes the Act has been more successful. The JOBS Act has two provisions that allow issuers to reduce the uncertainty of the IPO process. First, it allows issuers to “test-the-waters” and reach out to accredited investors before filing to judge their interest in a potential IPO. Second, it allows companies to file a confidential draft registration with the Securities and Exchange Commission. If the SEC’s comments are unfavorable or the company isn’t approved, the draft registration statement remains private. (In the past, any registration statement automatically became public, tipping off competitors about the issuer’s revenues, strategy and anticipated risks.) Both provisions help reduce the chances and costs of an unsuccessful offering to the issuer.

“We saw investors value the confidential filing and their ability to keep information private,” Chaplinsky says, noting that confidential filings jumped to more than 90 percent of issues following the passage of the JOBS Act. She found no evidence that investors penalized companies for filing confidentially.

Finally, does the JOBS Act succeed in its stated goal: spurring more companies to file IPOs? It’s too soon to tell conclusively, says Chaplinsky. Controlling for market conditions, she found no significant increase in IPOs, apart from a roughly 24-month increase in filings from the biotech and pharmaceutical sector. These companies, she notes, typically had few options other than an IPO for getting funding — many having disclosed in their prospectus that profitability might be a decade away. But as for widespread, renewed eagerness to pursue IPOs? Chaplinsky doesn’t see it. “It used to be quite a status symbol to be listed on an exchange,” says Chaplinsky. “Right now, there are many deep-pocketed companies looking to acquire growth through startup companies and the majority of entrepreneurs would rather sell out than go public.”

Susan Chaplinsky, Tipton R. Snavely Professor of Business Administration, is co-author of “The JOBS Act and the Costs of Going Public” with Kathleen Weiss Hanley and S. Katie Moon.