FORTUNE — For much of human history, people explained away the many things they couldn’t understand by resorting to gods, spirits, and fanciful tales. Life may have been nasty, brutish, and short, but the world that contained it was in some sense enchanted.

Then came the Enlightenment, with its emphasis on reason and science over superstition, leading to what Max Weber called the “disenchantment of the world.” People stopped blaming the devil, in other words, and started figuring out how things worked. It was a great time for the curious and the mechanically inclined.

But sometime in the middle of the last century, the veil descended once again. The postwar technological revolution served to re-enchant everyday life, giving us lasers and computers and other mysterious technologies that many embraced but few understood or could work on. The result was a great many magical gizmos (iPad, anyone?) but the decline of a long tradition of hands-on, do-it-yourself activity that formed a salutary culture of tinkering — one linked to such broader American traditions as self-reliance and innovation.

This tinkering tradition is a core American virtue, in the view of Alec Foege, who explores it, warts and all, in his new book The Tinkerers: The Amateurs, DIYers, and Inventors Who Made America Great. “Puttering around with the mechanical devices that surrounded us was practically a rite of passage,” he writes, “and for many, a way of life.”

Foege argues that tinkering has three essential characteristics. First, it involves “making something genuinely new out of the things that already surround us.” Second, it “happens without an initial sense of purpose.” And third, it’s “a disruptive act in which the tinkerer pivots from history and begins a new journey.”

Foege recognizes that tinkering can be virtual as well as physical — that it can involve, say, mobile apps just as it once involved carburetors. That’s in keeping with his thesis that tinkering, however threatened, isn’t dead in this country.

In his recent book Makers: the New Industrial Revolution, Chris Anderson foresees a return to individual and small group fabrication that leverages the power of information technology to, in effect, bring back tinkerers in a world enchanted not by mystery but by discovery and empowerment. Both authors emphasize the importance of collaboration, but if Anderson is mainly concerned with where we are going, Foege spends more time on where we’ve been.

Many of the Founding Fathers, he notes, were accomplished tinkerers, as befits such creative men living in an agrarian society with few mechanical conveniences. Franklin was of course the archetype, but Jefferson, Madison, and Washington were innovators as well, and Hamilton was “a fitting forbear to today’s financial tinkerers.”

Unfortunately, The Tinkerers itself is a not-entirely-successful example of the tinkering it purports to describe. The author works with materials all too readily at hand and sometimes seems to lack a clear purpose. Much of the book reads like a sketchy and haphazard history of American innovation, veering from the well-known story of Thomas Edison to the frequently cited tragedy of the Xerox PARC lab, which seems to have invented practically everything for a company that exploited almost nothing.

But among these well-worn tales are more interesting stories of modern tinkerers such as George Hotz, a teenage hacker who customized an iPhone to work on the T-Mobile system and later unlocked a Sony PlayStation 3. Then there’s the compulsively innovative Dean Kamen, whose invention of the over-hyped Segway scooter has obscured a lifetime of medical-device tinkering that has made him wealthy and improved the lives of people all over the world.

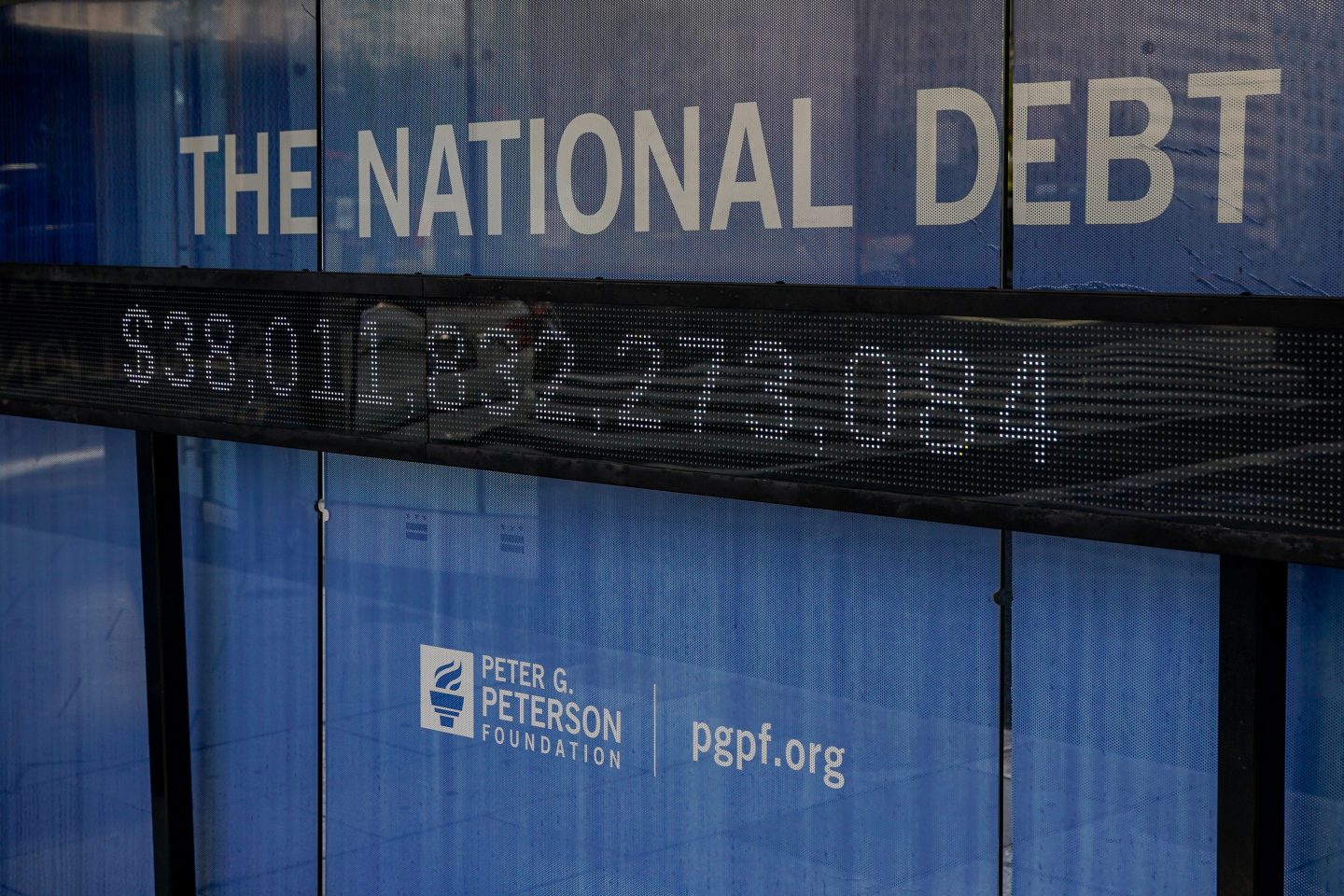

Knowledge is always dangerous, and the hazards of tinkering aren’t lost on Foege. He describes the RAND Corporation’s quantitative approach to public policy as a form of tinkering, and indicts it for helping fuel the notion that we were falling behind the Soviets in the nuclear arms race, and for the mindlessly data-driven worldview that led to so much trouble in Vietnam. More recently, he notes, tinkering in the financial world produced such innovations as the collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps that played an important role in the financial crisis of 2007-8.

Foege still believes in tinkering, and so should we. His biggest concern is that we aren’t doing enough of it. “The United States risks losing its hallowed tinkerer tradition — as well as the engine of innovation that fueled an unprecedented era of growth,” he writes. “Economic success has given us the time and resources to tinker, but it has also blunted our impetus to do so.”

Yet there are reasons for optimism. Capitalism is always being accused of undermining its own foundations, after all. Affluence and marketing subvert thrift, and the young decide to major in Madonna studies instead of engineering or physics. But over time, culture and economic cycles can have powerful corrective effects, prodding us to tinker anew.

And don’t forget about technology. Foege notes the advent of Kickstarter, for example, which enables crowd-funding of startups. “There’s some irony,” he writes, “in the fact that technology has helped return tinkering to a state not that far off from the way Benjamin Franklin must have experienced it: unpredictable, unencumbered, and swirling with possibility.”

Our Weekly Read column features

Fortune

staffers’ and contributors’ takes on recently published books about the business world and beyond. We’ve invited the entire

Fortune

family — from our writers and editors to our photo editors and designers — to weigh in on books of their choosing based on their individual tastes or curiosities.

More Weekly Reads

- David Fishof’s Rock Your Business

- Nassim Taleb’s Antifragile

- Holiday book parade

- Jon Meacham’s Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power

- James C. Scott’s Two Cheers for Anarchism

- Coffee table book nirvana

- Robert Greene’s Mastery