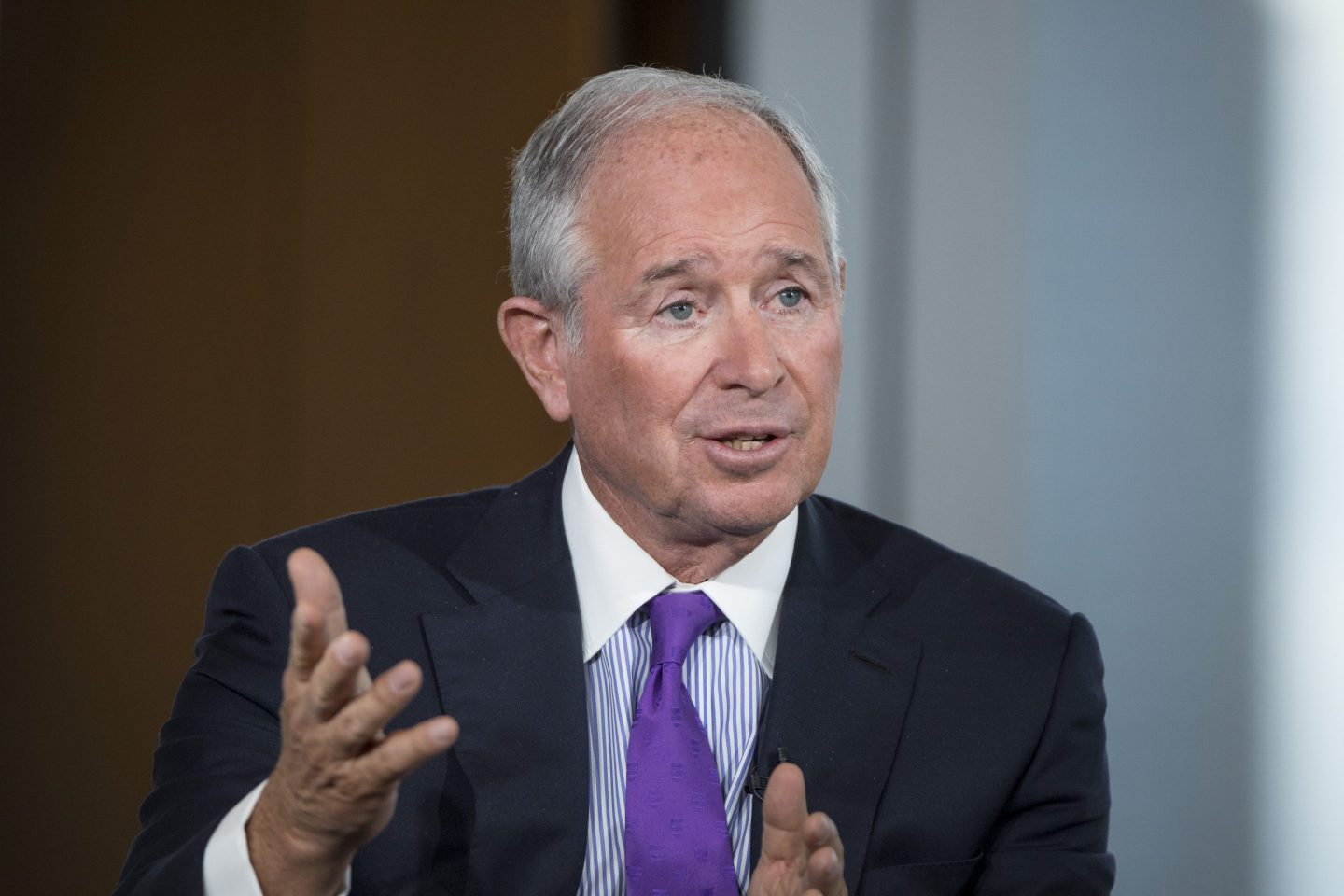

Albert Bourla is known for achieving impossible things as the CEO of Pfizer, a company he first joined in 1993.

Bourla led the company through COVID-19. He says President Trump called him every week, and his team worked around the clock to deliver.

Pfizer invented the first FDA-approved COVID vaccine and treatment, Paxlovid. Business soared to record revenue. Fast forward to today, and Bourla is chasing his next moonshot: solving cancer and capitalizing on other revolutionary drugs like GLP-1s, and the stakes are high. The company (which ranks No. 67 on the 2025 Fortune 500) is facing a patent cliff for some of its most lucrative drugs, and the COVID revenue bump it enjoyed is over.

Then there’s President Trump, who Bourla says still frequently calls him, but for a new reason: He wants Americans to pay less for drugs. In a new episode of Fortune 500: Titans and Disruptors of Industry, Fortune‘s Editor-in-Chief Alyson Shontell sat down with Bourla to reflect on Bourla’s impactful tenure so far and discuss he wants to take the company in the future.

Listen to the vodcast below:

Here’s some of what they discussed during their 45-minute conversation:

On his decision-making approach as a leader

- Why one of Bourla’s first actions as CEO was eliminating non-science-based aspects of the business, even though they represented 25% of the company’s revenue

- Why every corporation needs pessimists and optimists—but why optimists are the only leaders people will follow

On leading during the outbreak of COVID-19

- How he refused to let employees believe that creating a vaccine on short notice was impossible

- Why he used “emotional blackmail” on employees to get them to achieve an impossible ask — and why he feels “a little bit guilty” about it

On reprioritizing after the COVID-19 peak

- Why Pfizer directed most of its vaccine profits toward cancer research

- How confronting cancer is different—and less dramatic—than responding to a global pandemic

- How Bourla navigated the steep drop in profits and public attention as the world moved on from COVID-19

- Why he believes Pfizer’s long-term investments in R&D will protect it from losses due to declining COVID demand and the rise of generic drugs

On the acquisition of weight-loss treatment company Metsera

- How Pfizer’s early work on GLP-1 treatments failed, paving the way to the Metsera deal

- How rival Novo Nordisk turned an otherwise closing deal into “10 days of madness”

- How his mother’s optimism inspired him to not give up on the acquisition

On Bourla’s close relationship with President Trump—and the recent deal Pfizer made with the administration

- How frequent phone calls during the COVID-19 crisis forged a close bond between Bourla and President Trump—and why Bourla “never turned the page” on his friend

- Why Bourla agrees with Trump that Americans pay too much for medicines—and how the system that enforces that

- How Pfizer and the Department of Health & Human Services assembled a deal to lower drug costs in just 10 days

On the capability of AI to accelerate drug discovery and development

- Why Bourla believes the winners of the AI era won’t be those who choose the perfect vendor, but those who integrate AI most effectively

- How technology helped the company shorten the development time for Paxlovid, a treatment for COVID-19, from four years to four months

Read the transcript, which has been lightly edited for length and clarity, below.

Bourla’s upbringing in Greece and his parents’ experience as Holocaust survivors

Shontell: Monday, March 15, 1993 was the first day of the rest of your life. It’s the day that you joined Pfizer in Greece, actually, in the Animal Health Department.

I’m wondering how your upbringing in Greece may have shaped you into the CEO you are today, and might have brought you to Pfizer in the first place? I understand your parents were Holocaust survivors, so I just want to understand from you—what about your upbringing that you think helped you position yourself for the CEO spot?

Bourla: First of all, it’s a great pleasure, Alyson, to be with you. I have watched many of your podcasts, and they are all wonderful, and I’m very proud that you invited me to be part of it.

I grew up in a middle class family. My parents, as you said, were Holocaust survivors. Both of them. And I grew up in a city that had 55,000 Jews when my parents grew up. There were only 700 of us when I grew up. So it was an almost complete extermination that clearly left a mark in all the Jewish community in Thessaloniki, the city I was coming from.

My parents were not very rich, but we had everything we needed. They were happy. We grew up in an environment that was very well protected. So we were also encouraged to do things out of curiosity. I was [like] my father, who had ambition to become a scientist, and of course, he couldn’t. He wanted me to become a scientist. So I got that, I think, from him.

From my mom, I got more of her personality drive. She was someone that was extremely optimistic in life. She would think that every obstacle is an opportunity to do something better, and she would think that nothing is impossible.

She would use her experience of surviving the Holocaust, which was quite dramatic because she was scheduled to be executed. She was placed in front of a firing squad, but a Christian relative paid bribes and was successful at the last moment. So they removed her from the line and moved her back, and she could hear the machine guns killing everybody else.

So from her perspective, she could be someone who [could] bring hate for those that [did that], but never to us. She was always bringing to me, life is miraculous. I was there, and suddenly I survived. And look at me now—I have you and your sister. So nothing is impossible. That’s my mom. I think I took that from her.

A love of science, resilience, and optimism despite the hardship, that’s an incredible foundation.

Why Bourla didn’t want to join Pfizer—but hasn’t looked back since he did

So you joined Pfizer—it’s unique to be able to build a career within one place over the course of 30-plus years. If you look back on your time at Pfizer, was there a key milestone moment where you felt, Oh wow, I could be the company’s CEO. I could be on that path.

Only very, very late in my career.

I joined Pfizer in Greece, and I didn’t want to join the industry. My vision at the time was to become a professor working in academia, which is where I was working. I was doing my PhD in addition to being a veterinarian. But Pfizer really wanted someone there, and they made me an offer that I couldn’t refuse.

So when I joined Pfizer in Athens from Thessaloniki, I was thinking, I’m going for a sabbatical. About 32 years after, I feel that was the right decision. I loved it, so I never looked back. I never missed academia. I wanted to do a career in the private sector because I enjoyed the creativity, but also the dynamism. There’s less bureaucracy than the public sector, and that was fascinating for me. I stayed in Greece for only three years. I was offered, very early in my career, opportunities to go international, to have an international career.

So three years later, I left in ’96 and I went to Brussels, and then I took a different role, from scientific to marketing. From only Greece, to the marketing of the entire region, that felt even more intriguing.

And then I moved and I went to Poland, where my kids were born by the way, and I was a country manager. And then I became director of Eastern Europe. And then I went back to Brussels, and then in 2001 I came to the U.S.

So a lot of international experience and a lot of different growth opportunities in different departments and exposure to different areas of Pfizer. Do you think those were the two really key things to becoming eventually suited for the CEO position?

I don’t know if that made me suited for the CEO position, but it certainly shaped who I am. I had the opportunity to live with so many different cultures and work with even more. I learned to be respectful of the differences of others. I learned to be sensitive as to how you need to behave if you want to achieve results, if you want to inspire people.

There are different things that you need to say to the U.S. and different things that you need to say to a German. So all of that made me have a better understanding of the value of diversity, but also only when you manage diversity the right way.

One of the first moves that you really helped shepherd is—Pfizer had a couple of different businesses, and you wanted to make it very science-focused, less consumer-focused. And you made a decision to push out the consumer side, which was about 25% of Pfizer’s revenue at the time. Not a small or easy decision to make. I’m curious how you came in with that kind of conviction to make a big, bold change like that, versus just seeing the status quo.

First of all, you are right. It was 25% of the revenue at the time. It was not only consumer, it was two businesses that we divested, the other one was also not science-based. And the main goal was to create a company that is pure science-based, pure innovation-based. A company that will develop innovation but can change the world.

I felt that the company had all the elements to be successful in such a journey, and I took the risk. I pretty much was devoted to doing that, not only divesting the business that was not scientific, but also changing the culture, changing the capital allocation within the company. I increased the R&D budgets. I increased the digital budgets so that we can thrive in innovation. And then at the end of the year, when we were ready, COVID hit.

Bourla’s leadership through the COVID-19 pandemic—and what was needed to create and deploy a life-saving vaccine

I want to just kind of stress the magnitude of the change you had to make. One of the stats was that prior to COVID, you had been producing about 200 million doses of vaccines per year, and you had to scale that to suddenly 3 billion doses in a year. How do you tackle things like that, as an org that just seem unfeasible?

Yeah, that’s my mom coming out—that nothing is impossible, but how to convince others? And I found out through that process that when you ask people to do things that they perceive as difficult or impossible, the first thing that they do is to use all their brain power to develop the arguments— articulate them in a PowerPoint presentation—why can’t it be made? That’s always the case, and if you resist the temptation that rationally, that cannot be made, and you move the goal post to that’s what the world needs, it can be made.

But what the world needs is a reality, and we need the vaccine, and we need a treatment, or people will die. Our civilization, the way we know it, will be demolished. Financial disaster. It will have dear consequences in society.

So you move that and then without argument, you say, go and figure it out. Within a week, they stopped worrying about how to convince you that it cannot be done, and they started worrying how they can find ways to overcome the obstacles and make it happen. And this is when they can come and surprise you with how much they can achieve when they are focusing on how to resolve issues. That was the secret with Pfizer.

During the leadership time of COVID, you had signs over the office that said, time is life. And I’ve heard you describe how you motivated the team a little bit unfairly as emotional blackmail, where you would say, if we delay this even a month, I want you to calculate how many more people will die. That’s pretty dramatic. But do you think that was really essential to getting them to stop saying no?

I’m afraid it was.

I still believe it was emotional blackmail, because I was asking them to do something impossible, and then I was putting on their shoulders that if they don’t make it, people will die.

And that happened on several occasions when they came and they said, look, I think we need a three week delay on that. And then I said, why don’t you go and calculate how many people will die in three weeks? Come back and tell me. And yeah, I feel a little bit guilty about it, but I also know that it played a key role in not only saving the world and the economy and society to make them feel like the most important people on Earth. Those that were able to deliver, and they will never forget.

During the pandemic, one of the criticisms that Pfizer faced, despite coming out with this vaccine, was the profit from it, and also how pricing was figured out for other countries throughout the world. I’m wondering, if you think that that was handled in the right way, would you price things differently the next time? Would there be different business considerations in how you would do a future pandemic?

It was priced the right way. I don’t have any regrets about that.

It was very socially sensitive. We had the tier pricing. The U.S. and other rich nations had one tier. Then middle-income countries, they had almost half of that. And then the low-income countries were given [it] almost for free.

Now, in the U.S. and high income countries, the price that they had to pay was the price of a takeaway meal as much as you would buy today, or at that time. Your meal in McDonald’s, the COVID [vaccine] would cost the same. So it was very reasonably priced.

We made a lot of money because we made three and a half billion doses. Of course, you can make a lot of money when you do that, but it is not sustainable. Of course, because of our results, COVID went down. It was under control, so you don’t have to sell anymore.

The COVID business was obviously incredible, maybe a one time bump for your business. And you also are facing some very successful patents—people call the patent cliff. Over the next few years, some very lucrative patents will be rolling off, and generic drugs will be able to come onto the market.

There has been some concern about what Pfizer’s business looks like? How can it be healthy? How can it be strong when these two big cash cows for it are diminishing? How are you thinking about building a stable foundation and making up for the lost revenue of those two big money drivers and getting to revenue growth again? I think you said by 2030 or 2029 you expect to be back there.

We expect to be not only back in growth, but back in very strong exponential growth. COVID was a great success for the company—it skyrocketed us to all-time highs, saved the world, and gave us a lot of profits. In 2022, our COVID revenues went to $56 billion. The next year, in ’23, they dropped to $12 [billion], and now they are around $5 [billion] or $6 [billion]. So financially, for the company, it was a major hit, and that was reflected in our stock price.

At the top of the hill, you are the best company. You are the best named CEO. The people in Pfizer are the most proud employees in the world. Suddenly, to have a financial drop, it hurts a lot, and that creates emotional reactions for everyone in the company, including me. So it was a very difficult period for me, the year 2023.

But I do believe that the winners in life are not differentiated from the losers in life, because the winners never fall. They are differentiated because the winners always stand up again. That’s the big belief that they have. And that’s, I think, what we did.

We invested $23 billion dollars in new business development opportunity, although the COVID business was going down, because we knew that we need to do that to overcome both the COVID losses, but also, even more importantly, the loss of exclusivity, the patent cliff that we are going to face starting in ’26, ’27, and ‘28.

We went back to rebuild our commercial operations, to restore the glory of them. And ’24 and ’25 were spectacular years in the marketplace. And we went to restore the glory of R&D. We did significant changes in the research engine and significant acquisitions.

So I think we have all the elements that we need to weather the period of employees ahead of us, and emerge very strong with very strong growth, which will be based on us changing the lives of millions and millions of patients.

Where Pfizer is investing the revenue it raised during the pandemic—and its developments in fighting cancer

You had the vaccine the first year, and then the treatment the next year, and you over delivered.

I’m curious about what happens after you over deliver so spectacularly—how do you motivate them to ever do something else? And do something else that could ever be as great as that mission that they felt they were really saving lives, saving the world? Really, the purpose was so clear. How do you create a next purpose for them? And then, as a CEO, how do you create a next purpose for yourself?

We used all the profits that we were able to generate during the COVID period, which was significant, to reinvest. And the area that we picked was cancer. This is where the bulk of our investments were, and for several reasons.

One, because we were already good at cancer, and the second was that we had the fantastic opportunity, with the acquisition of Seagen, to double down on it. Also because cancer is so personal, and cancer affects so much the world and affects so many of our colleagues. We saved the world from COVID, now we’ll save the world from cancer.

So that was the goal, and that’s what we try to do, and I think we are delivering on it. We’ve had some remarkable readouts on cancer. Cancer, it’s not going to be as dramatic as COVID. You don’t have a vaccine one day, and then the next morning you do have a vaccine. Science fights cancer for decades, so the improvements will be incremental. But when you are doubling the survival rate.

In the last two years we were able, in massive cancers like bladder cancer, prostate cancer, to double the survival rate. Colorectal cancer, which is a cancer that affects so many young people, that’s transformational. Those people are feeling that what they do has a purpose that they can’t find anywhere else.

As you look at your pipeline of products, where do you think the most value is going to be derived in the future? It sounds like cancer is definitely a bucket.

Right now we orient more than 40% of our yearly R&D expenses to cancer.

And how much do you spend on R&D a year?

$11 billion, approximately. So it’s a significant amount that goes to cancer.

Right now, in the U.S., we’re the number three company in cancer, but we have a very strong phase three, very strong phase two, very strong phase one. And scientists are tackling cutting edge technologies to be able to deliver solutions for cancer.

Pfizer was always a primary care company and company that thrives in marketplaces where massive manufacturing is needed. Which is the case in primary care and or vaccines—thousands and thousands of patients in clinical trials and massive commercial execution with field forces and marketing teams around the world.

And for us, the big play on internal medicine was obesity. We were very early with GLP-1s. We believe that GLP-1s could become a significant differentiator, and we developed a pipeline of oral GLP-1s very early on that, at the time, no one had. Unfortunately, the products didn’t work. They had good efficacy, actually good tolerability, but they had toxicity in the liver, which we discovered.

And of course, we stopped the program, and that’s why now we had all this infrastructure. We have the right to win in this marketplace, but we don’t have the portfolio, and this is where the acquisition of Metsera came, but I think positions us now as a second very big driver of growth to be the obesity market.

Bourla on GLP-1s and the competitive race to acquire Metsera

I want to talk about the Metsera acquisition, because it is big, and it’s been described as a Game of Thrones between you and Novo Nordisk to acquire that company. Well, you’re the king. You’re sitting on it.

Can you take me behind the scenes of what it’s like to do a major acquisition like that? It sounds like you made a bid in August. The price went up significantly—it was like a $7 billion sum that you offered at the time, it went up to $10 billion. What’s it like behind the scenes of a major acquisition like that?

Usually things are moving very fast at the last moment, but they are cooking for a very, very, very long time.

We were flirting with Metsera before they got into an IPO when the founders had just built a pipeline and were looking for opportunities. We knew their pipeline, we were watching it. We did repeat due diligence to see their data. And there was a period of time that, after their IPO, our molecules had failed. So we felt it was the time to make a move, and then we started reengaging with them. Things were going up and down for a period of time, but eventually we were able to sign a deal with them. Took quite a bit of time, took several meetings between me and the principals of their board and the CEO and between our scientists.

And we had a deal, and everything was moving to a close, but then we had this bid from Novo Nordisk that complicated things. So it was, I don’t know, 10 days of wildness. As you described it, “Games of Thrones.”

Were there any moments where you thought, shoot, we’ve lost it?

Of course, I was considering that as a possibility. But again, my mom came to me, don’t you dare. We will not lose it. I told everyone, that’s it. We are going to get it. Don’t worry. Because, you know, my people were devastated. There were people that gave months of their life, day and night, to develop protocols for how these products will be developed in case we were buying them. Day and night getting into meetings with the Metsera colleagues to make sure that they will go. And then suddenly they see Novo coming and complicating things, and what we thought was in our pocket, suddenly, maybe was not. So I reassured us that we were going to have to make it happen.

Bourla’s relationship with President Trump and Pfizer’s deal with the Trump Administration to lower drug prices

Recently, there was big news with the Trump administration. You and President Trump announced that Pfizer would be participating in reducing the cost of some drugs for Americans to the tune of about 50% in some cases or more. You also announced that American manufacturing would be brought here into the states. You already have 13 facilities, I believe, in the United States, but even more will be committed.

I’m wondering, how did you and the president arrive at this? What was behind the scenes of the deal?

I knew the president from his first term. I knew him because he was, as you remember, personally and heavily involved in managing the COVID crisis, and we were among the few companies that were in the forefront of developing a solution. So he would call me every week, and he would go into details. And he would ask how the FDA can help, how Operation Warp Speed can help.

Because we had setbacks and successes during that period, which I was explaining to him, we created a bonding. No matter what your political views are, when you are working to save the world—that creates a bonding.

And of course, I have a tendency to never forget my friend. So when he left, I never turned the page on him. I was maintaining a human relationship with him. And then he came back to the surprise of all, if not many, or many, if not all, and we picked it up again from where we left it.

And we started discussing the future of health care in America. And it was very clear to me that what was in his mind in the first administration had now become a very intensive itch that needed to be scratched. He was very adamant that he can’t tolerate that other rich nations pay less than Americans are paying, or the American healthcare system is paying, for the same medicines.

“It was very clear to me that what was in [President Trump’s] mind in the first administration had now become a very intensive itch that needed to be scratched.”

Albert Bourla

Well, why would Americans pay more?

I fully agree that was not a sustainable situation. It’s not only in medicines, by the way. If you compare the price of a physician fee in Germany or in the U.S., it’s a fraction. If you compare an MRI, it’s a fraction. Open heart surgery is a fraction. And medicine is the same.

But it was very clear to me that medicine is a way more sensitive issue because it affects the out of pocket people. In the end, the president was adamant. So I knew that the genie was out of the bottle and we needed to find a solution.

That same time, he came with his views on tariffs that were posing a big threat to us, because over decades, the way that manufacturing operated—all our patented products were made offshore. The off-patent products are made here. The vast majority of our medicines are made here, but the very expensive medicines are made outside, for very, very different reasons. So we couldn’t change it overnight. A manufacturing site, in our case, needs at least five years from the day you break ground all the way until a product comes out of the door. And tariffs were imminent.

So I realized that those two things need to be resolved. And they were creating significant uncertainty over our entire sector. The multiples of the sector were at historical low this year, and the funding for biotech was at a historical low this year. And those two were an important reason for that.

So after lengthy discussions and negotiations, basically, I came to the conclusion that we need to cut a deal. And we had very regular discussions with HHS, and I told them, I’m ready to cut a deal. Let’s sit and do it, and within 10 days, we signed. Once you make the decision, that’s it. You move very fast.

That’s great, and I think Americans will feel it.

I think Americans will feel it, and the industry will feel it. I knew when I did that that I’m going to drive the entire pharmaceutical industry in this direction. It will be very difficult for anybody else to take a different path.

What does that feel like as a leader, to know that you can move a whole industry with your decisions and the pressure that puts on you to make sure you’re making the right ones?

A lot of pressure. I knew that it was not only about Pfizer, it was about the industry. And when we speak about the pharmaceutical industry, we’re talking about the lives of our kids, of our parents, of our loved ones. This is where innovation turns into people saving lives or having much better lives.

So I knew it would be consequential, and I didn’t only want to resolve a financial issue. I wanted to make sure that I create the conditions that funding will go back to biotech, so biotech will still be very productive.

That was a game changer for all of us, that could go one way or another. And I think we found the perfect balance and solution to drive things positively for the patients and for the industry. And I’m sure everybody will fall into that.

More on affordability—and why Bourla thinks vaccine misinformation will ‘correct itself’

Affordability comes into the question, there’s a lack of trust in general in our nation. I think the health care and pharma industries have felt it quite a bit from consumers, and I think drug pricing is one of them. People don’t understand why American drugs are so expensive.

I think also from the pandemic, despite the fact that Pfizer rode to the rescue and should be viewed as a hero very much, there’s also skepticism about how vaccines were enforced on the country, and people have feelings about the medical advice they were receiving at the time.

What do you think about those criticisms, and how do you start repairing trust as a leader who can move the whole industry?

I think Americans complain about drug pricing, not because they have in mind what Germans are paying. They have no idea.

They complain about drug pricing because they know that they have to pay way more money than when they do an MRI, when they do even a hospital visit, when they do a physician’s visit. Because the way that the system works is, you have insurance and insurance makes sure that everybody is flattened out. So you’re not facing the catastrophe of 10 visits to the doctor, three MRIs and a surgery, and then bankruptcy because of that.

That’s not happening because it pretty much is working in a lot of cases, but not for medicines. Because for medicines, we have an anomaly in the way that the PBMs, or the people that are negotiating the prices, can actually make their money. Not out of a fee for their service, but out of the spread between how much is the net price and the gross price. Because someone needs to pay that difference, they are pushing it to the patients.

So basically, people are paying for medicine as if they don’t have insurance. Although they have in the U.S., one of the most expensive insurances that exist in the world, that’s what created a lot of pressure. Because they didn’t know who to blame, and for many, many years, they were only blaming the pharmaceutical company.

I think that has changed, both in the public opinion, but also in the feelings of politicians in Congress. We can now see bipartisan bills, which is very rare in our days, about resolving and transforming this middlemen intervention. Once we fix that, people will see that they are out of pocket. It is reasonable.

I think it’s easy to criticize the Biden administration, many people will say maybe they shouldn’t [have] put mandates. Many people said that they should. They did the right thing, frankly, for the U.S. I was always under the impression that we should not have mandates, because Americans have a very free spirit. It’s very different from Scandinavians. It’s hard to control. And if you do it, there will be significant backslash.

Let’s understand that mandates for vaccinations were not only in America. They were in France, Germany, Israel, Romania, every country in the world. They all did the same, all of them. All of them mandated masks, all of them mandated vaccines, and all of them had social distancing. In the U.S., everything that’s mandated by government backfires, and I think that’s what happened during that time.

But this doesn’t mean that it was necessarily the wrong medical advice. It was the same in every other country. It was maybe the wrong political way of going after it, but a lot, a lot, a lot of lives were saved.

I think that’s an important point to remember. I know you’ve said science will win in the end. There’s a lot of misinformation, disinformation out there, but vaccines are still such an important part of preventative care.

Not still—they are the most important part. They are what increased lifespans in the 20th century by more than 30 years. It is predominantly because of the discovery from Louis Pasteur, back in the day, of a vaccine against rabies. And then we realized that we can control diseases that were decimating our population.

Child mortality was huge at that period of time, and has all been reversed because of vaccinations. The disinformation that circulates right now is not only without any merit, but it is very dangerous because it discourages people. This is scientific information. Not everyone is qualified to understand the plusses and the minuses.

That’s why we were constantly relying on the opinion of the experts. But experts were not lawyers. Experts were doctors, right? Experts were people that had credentials in the scientific community, that were elected from the American Association of Pediatricians, and they could issue a recommendation by the CDC that had an independent committee where people were debating, and that’s how people used to do it. When they hear them saying, do it or don’t do it, they would follow.

Now, unfortunately, we have people, but they’re not like that. They are lawyers or they are one scientist out of, not 100, of 10,000, that disagree with what the remaining 9,999 are saying, but they get a very big microphone and they confuse people, and that’s unfortunately what we are living today.

Do you think that that will sort itself out, or are you worried that this is a continuing trend?

No, I think it will correct itself. And I hope sooner rather than later. My only concern is if that will correct itself because of political changes, or if that will correct itself because so many people dying will trigger political changes. These decisions have consequences, absolutely dear consequences. And we see that with measles right now, and you can see it with many other things. Hepatitis, you name it.

How AI can contribute to science—and what the U.S. can do to stay competitive

I want to look forward to what you’ve called the “science renaissance” moment we’re in. There’s so much happening with AI. People consider it to be the most transformative technology, perhaps to ever exist. They liken it to electricity, and it will touch and transform everything.

I’m curious, from your vantage point at Pfizer and in the pharma industry, how much has AI already changed what you’re able to do? When it’s fully realized, how much more is there to gain?

It’s changing dramatically what we can do. It certainly can do way more than we are using it for so I think the winners in that field will be separated from the losers, not by their ability to select the right technology or the right vendor, but their ability to transform their own organizations in ways that will embrace AI, will overcome resistance, will overcome the pessimism that AI sometimes creates. Oh my God, we are going to lose our jobs, rather than the optimist, Oh my God, we are going to cure cancer.

And that’s, I think, what will happen with the current technology. But technology and AI is really moving very fast, not in a year or two, but in weeks and months, and could transform the way that we discover, develop, and manufacture medicines.

Is it speeding up the R&D process already, or the drug discovery process already?

I will give you a good example. We spoke a little bit about the vaccine, but we didn’t speak about Paxlovid, which was the treatment against COVID.

Paxlovid was a medicine that was discovered and we finalized the pre-clinical piece in four months. Usually it takes four years. We did that by using machine learning. Does it work? Is it safe? It’s happening in the lab, and it’s happening by formulating millions of molecules with robots, and then we test them, and then we try to discover among those millions, the ones that are very successful.

Usually, let’s say 3 million molecules, will take four years. With Paxlovid, we use a computer not to discover medicine, but to design it. And the computer designed 600 examples of that. So we synthesized 600 molecules and we tested them in the tubes, then in animals. And then, based on that, we select very few, but we test in primates, and then one that we tested we started studying in humans.

So four years to four months, that’s dramatic, and that has translated to hundreds of thousands of lives.

Albert, you run a global company, and you have a vantage point from, yes, the United States, but really from everywhere, including China.

I’m wondering, as you look at the landscape in pharma and in medicine and where everything is headed, what you see happening abroad, particularly in that part of the world, and what we need to be aware of here in the United States?

You know, in the last 20-25 years, the U.S. dominated medical, biomedical research. Everything is happening here. Even European companies are doing that here. And the first time that someone is challenging the U.S. dominance is China, not Europe.

Europe is really going backwards, I would say, in terms of technology. And Japan is not progressing at all. Actually, they are also going backwards. But the Chinese are going forward with double the speed and half the cost of what we are, and they are investing tremendous amounts behind their innovation.

They are investing in biotech, and they have created awesome biotechs. They are investing in universities. They are investing in hospitals that can do research, and they are producing right now in peer magazines. All scientific magazines that are so difficult to get [published] in, because the quality needs to be extremely, extremely high and very competitive.

They dominate CRISPR, a gene editing technology that we discussed. In 2024, more than 40% of the publications were from Chinese authors in structural biology, which they were always good at. More than 60% were from Chinese authors.

So it’s not that China right now are copying. They are copying, like we copy one another, but they are producing very high science that’s good, I think, for patients.

But from our perspective, if we want to be the ones who offer the solutions, we need to take that seriously, because there is—and if I have to give advice to all the people that worry for national security reasons about that, then probably they’re right, but they put too much emphasis [on it]. 80% of their focus and energy is how to slow down China, rather than how to become better than them.

80% of our effort, 80% of our brain power, should go to—what do I need to change to become better than them? How can I take the unique advantages of our political system, of our university, of our biotech and do the right policy changes? Do the right investments so it can become better than them? And that’s what will define the success or failure of the U.S. biomedical community.

Yes, the idea of slowing the pace there seems like a lost cause. I mean, they are off to the races. It’s no slowing that momentum.

So we will never slow them down. They are very good, and we should just become better if we want to win.

Bourla’s predictions for the next scientific breakthroughs

When you look ahead, what kind of medical advancements do you think will be achievable in our lifetime? That, when you were joining Pfizer 30 years ago, you would have said, No way?

I think we will have a cure for cancer, for many of the cancers, at least.

Even late stage? What about stage four?

I think the interventions will start earlier and will have better results, but you will find ways to have dramatically better results in later stages, which is what we are doing already right now. I think that we should be able, as I said, to cure. But the remaining that are not cured will become chronic diseases. You can live with your cancer like you live with your diabetes. Do something in the morning, or you are a little bit careful with something, but you have a normal life that is not predicted to end within two or three years. That’s big.

I think we will resolve neuroscience problems. Alzheimer’s, even Parkinson’s are things that right now we don’t have solutions for. Or the solutions that exist are, let’s say, not highly satisfactory. I think we will come to highly satisfactory solutions, and AI, together with biology, will play a key role.

Bourla’s advice to leaders—and why companies need a balance of optimists and pessimists

As you look at your 30-year career here, and hopefully many more years as well, and you’re leaving advice for other future leaders, people who want to successfully run major companies and lead with integrity their workforces to do incredible things, what advice would you leave them with? What’s the one big takeaway that you’ve had from all of your experience that you think other leaders could benefit from learning?

I guess that I will say one thing. In big corporations, like in families, like in groups of people that do something together, you need to have both pessimists and optimists. The optimists have the vision. The pessimists land you to reality and help avoid pitfalls. But I will give two lines of advice.

One, it is that pessimists are usually right, but nothing great on this earth has been accomplished without an optimist behind it. And second, for a leader, we all appreciate having pessimists around, but no one follows them. Maybe people listen to them, but the pessimist doesn’t have followers. Everybody follows an optimist.

That’s the one who can inspire them. So you see my message—you want to be a successful leader? Bring a team around you that lands you to reality, but be the optimist.