After huge rallies or selloffs, it’s often pointed out that the stock market is not the economy, or that Wall Street is not Main Street. But that divide is getting blurrier.

That’s because higher asset prices are spurring consumers to spend more freely than before, and consumption represents about 70% of GDP. In fact, this so-called wealth effect has become more potent in just the past 15 years.

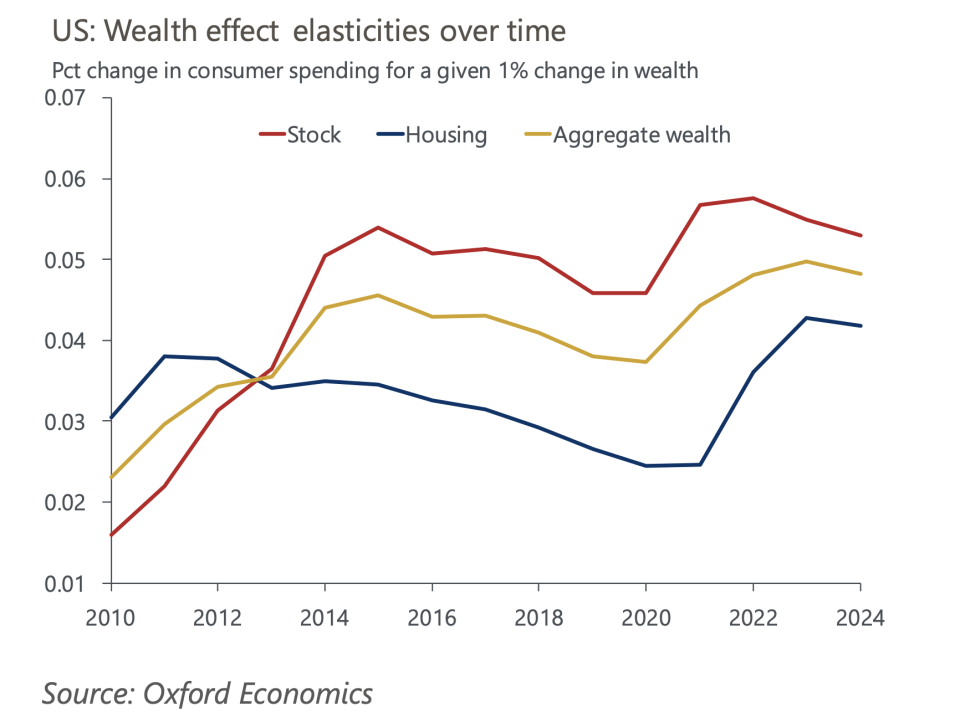

Today, every 1% increase in stock wealth translates to a 0.05% uptick in consumer spending, according to a note last week from Oxford Economics lead U.S. economist Bernard Yaros.

In other words, a $1 increase in stock wealth leads to a $0.05 marginal propensity to consume, up from less than $0.02 in 2010. Meanwhile, every $1 increase in housing wealth leads to a $0.04 bump in consumption, up from $0.03.

“As households see their wealth rise, they turn more sanguine about their personal financial situation and are more inclined to loosen their purse strings,” Yaros wrote. “Increases in wealth will also propel spending by allowing homeowners to extract more equity from their houses or to liquidate appreciated stocks to fund their current consumption.”

He sees the wealth effect sending the marginal propensity to consume even higher in the coming years because retirees will comprise a bigger share of the population.

Given that they already enjoy a bigger net worth than younger generations do, retirees will rely more on their wealth to support consumption after they stop working and earning an income, Yaros explained.

On top of that, the ubiquity of digital media means consumer sentiment reacts even quicker to market news, reinforcing these wealth effects, he added.

This more powerful wealth effect could help explain why consumer spending has stayed resilient. Even as President Donald Trump’s trade war has kept inflation sticky and made businesses more nervous about adding workers in an uncertain landscape, AI is still propelling the stock market to new record high after record high.

At the same time, the stock market has grown more dependent on AI-related stocks, such as chip leader Nvidia along with so-called hyperscalers like Microsoft and Google.

Based on his wealth-to-spending math, Yaros estimated that stock market gains in the past 12 months from the tech sector alone will boost annual consumption by nearly $250 billion, which would account for more than 20% of the cumulative spending increase.

“While the stock market is not the economy, the latter risks greater whiplash from the ups and downs in the former,” he wrote.

Analysts at JPMorgan also looked at the the link between the AI boom and consumers in a note last month. They estimated U.S. households gained more than $5 trillion in wealth in the past year from 30 AI-linked stocks, raising their annualized level of spending by about $180 billion.

That represents just 0.9% of total consumption, but JPMorgan noted that it could go higher if AI spurs gains in a broader array of stocks or in other assets like real estate.

And stocks are not limited to wealthier Americans either. A survey released last month from the BlackRock Foundation and Commonwealth showed that over 54% of Americans earning $30,000 to $79,999 a year are retail investors in the capital markets. And more than half of that cohort began investing in the past five years.

To be sure, the wealthiest still spend the most dollars, and the emerging K-shaped economy has magnified their impact. Research from Moody’s found that the top 10% of earners accounted for half of spending in the second quarter, a record high.

Michael Brown, senior research strategist at Pepperstone, attributed that to the wealth effect from stock and real estate gains as well as from income disparities.

“Tying all this together produces two things—an economy increasingly reliant on discretionary spending among higher earners, and higher earners whose discretionary spending is reliant on risk assets remaining buoyant,” he said in a note on Tuesday.

This dynamic means central bankers at the Fed who control monetary policy and lawmakers in Congress who control fiscal policy have a greater incentive to support the stock market, Brown added.

That’s because the wealth effect can work in the reverse direction, meaning falling asset prices will slow spending and the economy.

“What we have, then, is an economy that’s tied increasingly closely to the fortunes of the equity market, and an equity market that’s increasingly tied to overall consumer spending, which coupled together result in stronger ‘put’ structure to backstop risk assets, with fiscal stimulus continuing, and monetary backdrops becoming looser,” he said.