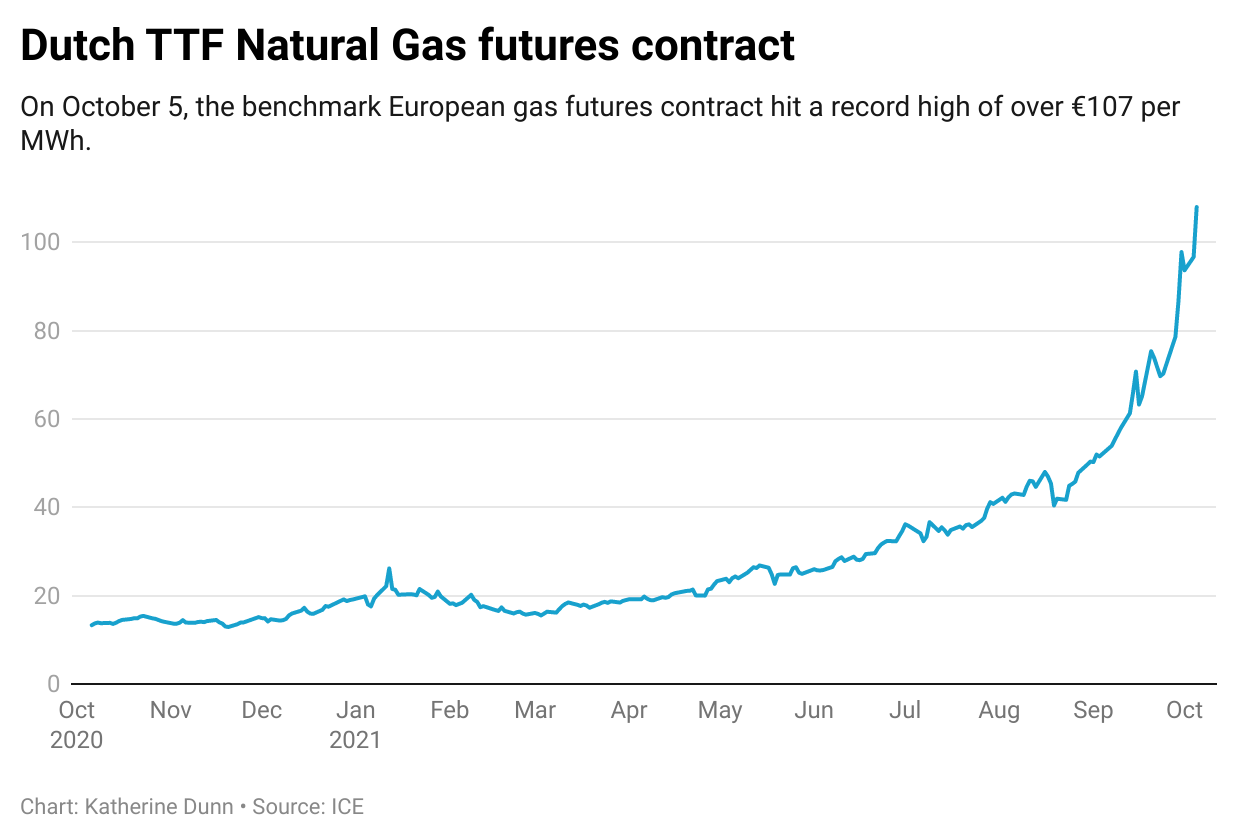

Throughout Europe’s autumn of energy discontent, natural gas and electricity prices have hit records almost daily, with natural gas contracts on the Dutch market reaching €107 per megawatt hour (MWh) on Tuesday—their highest price in, well, ever. Faced with untenable costs, energy providers have gone under, fertilizer plants have shuttered their factories, and governments have rushed to bail out consumers, attack windfall energy profits, cut taxes—anything to stop the bleeding.

But for every loser footing a bigger electricity bill, there’s a winner—and the energy crunch’s winners have won big.

Those winners work in just-in-time energy delivery. The sudden rise in demand for electricity on the European grid—the effect of the end of COVID lockdowns—has been hard to meet for a system that is increasingly dependent on renewable energy sources that are by definition intermittent (no sun at night, and the wind stops blowing sometimes, etc.). As demand spikes and supply vacillates, then, some source needs to fill the surges of electricity demand—something flexible enough to be turned on at the flip of a switch.

The switch that fills these surges is something called a gas “peaker,” a small generation plant that converts gas to electricity and is turned on at times of peak electricity use, for a very high price. Normally, the use of peakers would be regarded as a one-off. But as the world emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic and the demand for electricity surges across Europe, the plants are being switched on weekly—and their owners, who have quietly been building up a portfolio of plants, either from scratch or by refurbishing older gas or coal plants, are smiling at their foresight.

“If you described the scenario we are in now, someone would call it a 10-year event. Now the reality is that it’s happened three times in the last month,” says Matt Clare, founder of Arlington Energy, a developer and manager of energy transition assets including peakers.

The winners

With the price of gas more than tripling this year alone and the demand for flexible energy sources increasing, any business exposed to gas is likely to reap the returns. Gas producers Equinor and Gazprom are poised to benefit from the gas markets staying tight into 2025, Bank of America analysts said in a note placing “buy” recommendations on their shares.

Those businesses running the machines turning gas into electricity to balance the grid are also coming out on top.

Arlington’s Clare says he and his partner started the firm to invest in gas peakers after they connected the dots on a pattern showing coal plants being decommissioned, few nuclear plants being built, and a general distaste for using very large gas plants: “They’re old, they’re bulky, they’re very carbon intensive. They need to run for eight hours to make a decent return,” he said.

So a new asset took its place.

“Gas-peaking is not as sexy a buzzword as batteries, but they’re pretty mandatory in the [energy] transition,” Clare says.

And they are profitable. At the start of September, when little wind was coming from the North Sea, the U.K. paid a power plant a record high £4,950 per MWh ($6,850) to fire up a gas-fired peaker plant on short notice for 30 minutes.

“Gas being high puts up the wholesale prices, so as long as that continues—which it will as half the country runs off of it—then that margin will remain,” says Clare.

Anthony Catachanas, CEO of Victory Hill Capital Group, another asset manager that owns a portfolio of gas plants, called being prepared for the need for peakers “a matter of anticipation.” Catachanas’s firm is taking peaking a step further, capturing the CO2 emitted from the gas plants to sell back to the meat and packaging industry, which is also facing shortages at the moment owing to a lack of CO2 coming from their usual source—fertilizer plants that have shut down because of…high gas prices.

Catachanas says the real advantage to the business model is that utilities provide him with a spark spread, or a fixed margin between the revenue from power and the cost of the gas: “They’re fixing the cost of the gas for me for a five-year rolling basis of up to 15 years. This is unheard of.”

Victory Hill Capital Group boasts a 24.2% equity return on its investments, while pure-play renewable funds often reach returns in the single-digit range. Even Bank of America analysts agree, recommending utility investors “steer clear of the storm focus on pure-play renewables” such as Spanish renewable companies EDP Renováveis and Solaria Energia y Medio Ambiente.

When will gas stop winning?

Natural gas prices and electricity prices have always moved in tandem, and as gas prices rise in the face of spiking global demand, utilities are expected to pass 70% of electricity prices to consumers and industrials in 2021 and 2022, according to Bank of America analysts.

“Until we create and have a balance in the grid, gas prices are going to play a very important transition role and will drive energy prices,” says Victory Hill’s Catachanas. He notes that while there is consensus that there will eventually be a decoupling of electricity and gas prices, he doesn’t expect this to happen for 20 years.

For Clare from Arlington Energy, little will change for at least a decade without a creation of new power generators that are better than gas peakers at handling flexibility.

“I don’t see anything really resolving this correlation for a long time, unless some really different assets” enter the market, he notes. (If he knew which asset that was, he quips, he “would be a rich man.”)

Until a natural decoupling takes place, governments will have to intervene to separate the prices. France was the first to do so during this round of high gas prices, blocking any further natural gas price hikes and putting the kibosh on a planned increase in consumer electricity tariffs scheduled in February. Spain intervened as well, announcing cuts on the taxes applied to consumer electricity bills as well as a levy on “windfall” profits at power companies.

France and Spain have also joined forces to demand changes to the EU’s energy market rules. Before a meeting of eurozone finance ministers, Bruno Le Maire, France’s economy minister, told reporters, “It is time to have a look at the European energy market. It has one major downside, which is the alignment of electricity prices with the price of gas.”

More must-read business news and analysis from Fortune:

- CVS Health is about to turn hundreds of its drugstores into health care super-clinics

- 2021’s Most Powerful Women

- Another round of student loan forgiveness looks imminent—it could come this week

- She ran Bumble’s IPO while being treated for breast cancer. Now she’s becoming a CEO

- Can new CEO Fidji Simo turn Instacart into more than just a delivery company?

Subscribe to Fortune Daily to get essential business stories delivered straight to your inbox each morning.