Regulators at last have finalized the Volcker Rule, which bars banks from speculative trading. For that, they should be commended. Unfortunately the 71-page rule, which comes with 900 pages of explanations, has renewed debate over mounting regulatory costs and whether the benefits outweigh them. J.P. Morgan Chase — whose halo in Washington has been replaced by a big bull’s-eye — estimated in 2011 that its increased costs for compliance and controls would be about $3 billion over the “next few years.” But JPM, which generated $56 billion in earnings since 2011, can handle it. And if better controls help the bank avoid litigation and incidents like the $6 billion London Whale trading loss, it will be money well spent for its shareholders.

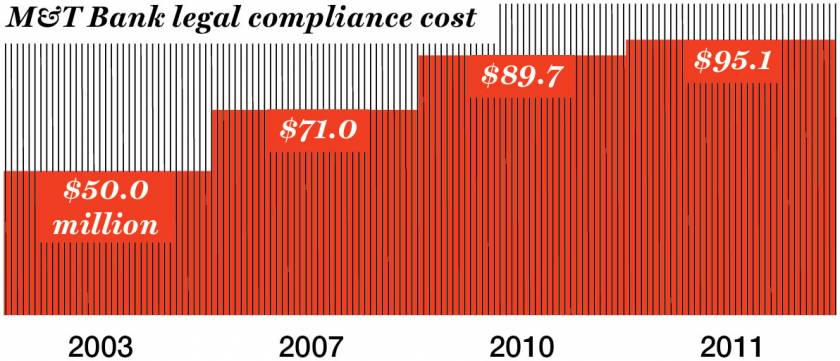

The benefits are less clear for regional and community banks. Many of the new regulations have hefty, fixed startup costs, which disproportionately impact smaller institutions. For instance, Buffalo’s M&T Bank estimates that its annual compliance costs have nearly doubled, from $50 million in 2003 to $95 million in 2011, more than 10% of its 2011 earnings. Similarly, at a recent conference at the St. Louis Federal Reserve, one state bank survey reported that compliance costs are eating up 10% to 15% of community-bank earnings. The irony is that most small banks did not make dodgy mortgages or hold the high-risk derivatives that created losses for the big banks.

While I strongly support financial reform, I would be the first to admit that more is not always better. Here are four suggestions for making regulations less costly and more effective:

Simplify capital requirements. In the late 1990s a group of international regulators decided that big banks should be able to use their own risk-management tools to determine how much capital they needed. In 2004 this controversial framework was adopted for European banks and U.S. investment banks, giving them leeway to dramatically reduce their capital, and they did. The results were disastrous.

Regulators have since added more bells and whistles in a futile attempt to fix this flawed and complex framework. According to research at the Bank of England, the rules require as many as 200 million calculations (vs. about a half-dozen under the old standard). “Nobody trusts it,” one senior risk officer at a large bank admitted to me.

Scrap it. There are simpler alternatives, such as limits on leverage and standardized rules for measuring risk.

Streamline money-laundering rules. The cost of complying with money-laundering and terrorist-financing rules often doesn’t make sense. When a business or household transmits more than $3,000 across our borders, U.S. banks have to independently review it and make detailed records. That makes banking services particularly expensive for smaller U.S. businesses that operate internationally. The government should instead create procedures for legitimate businesses to freely send and receive money without banks having to investigate each transaction. It would be a kind of global-entry program, except that instead of streamlining international travel, the program would make it easy for honest businesses that have undergone thorough background checks to transfer money.

Focus mortgage standards. Back when banks kept their loans instead of packaging them into securities and passing the risks on to investors, default rates were below 2%. Nonetheless, community banks that still follow this “portfolio lending” model have been hit with a slew of new rules telling them how to make and service their mortgages, while regulators have done little to fix securitization. The rules are an unnecessary burden.

Adjust the Volcker Rule. This reg rightly prohibits use of the federal safety net for high-risk, speculative trading. But why apply it to smaller banks that take deposits and make loans? If a bank holds a minimal amount of securities and derivatives, regulators should exempt it.

Fortune contributor Sheila Bair is former chair of the FDIC.

This story is from the February 3, 2014 issue of Fortune.