AI is entering a new phase: its 2.0 era. AI 1.0 was built on unstructured data that applied general machine learning to broad business problems. It marked the shift from experimental AI into early operational and agentic systems, anchored in the belief that larger models would naturally yield the most powerful results. This concept was reinforced by hyperscalers racing to build ever-large frontier models, creating an arms race that drove breakthroughs but also unsustainable compute demands and rising infrastructure costs.

AI 2.0 is different and challenges that belief as larger models are proving far less valuable in practice. Rather than modeling language or statistical likelihoods, AI 2.0 focuses on modeling real world dynamics. It leans on physics-informed machine learning – rigorous, simulation-driven models grounded in differential equations but accelerated by AI. These models don’t hallucinate; they compute and predict within the constraints of real world operations, making them far more suitable for production environments. This shift also reinforces that enterprises can no longer rely on hyperscaler economics alone. Training frontier-scale models requires compute footprints only a few providers can support, pushing organizations to rethink whether “bigger” is even accessible, let alone optimal, for their use cases.

Ultimately, the defining characteristic of AI 2.0 isn’t scale, it’s restraint. We are moving toward AI systems that know when to stop thinking. These are models engineered for precision, cost efficiency, and sound reasoning rather than endless computation.

The Transition from AI 1.0 to AI 2.0

AI 1.0 was built largely on inference, and dominated by experimentation and proof-of-concepts, where organizations optimized for demos and benchmarks rather than operational outcomes. The primary question wasn’t whether AI could scale economically or reliably; it was simply whether it could work at all.

Within this phase, many leaders fell into what became known as the “accuracy trap,” where they optimized for accuracy alone, rather than compute or contextual awareness. Models that looked strong in controlled environments ultimately failed in actual deployment because they were either too slow for real world demands or too expensive to scale with healthy unit economics. The instinct was to start with the largest model possible, assuming that adaptation would naturally improve performance.

AI 2.0 reframes this thinking. Leaders are now accountable for measurable ROI, not demos or benchmark scores. In 2.0, we need to stop training models to know everything and instead train AI models to simulate what matters. It’s a more specialized paradigm, where the goal is to learn and perfect one or several capabilities rather than chase generalization for its own sake.

In AI 2.0, every industry – from healthcare to manufacturing to financial services – will have the ability to build smaller, domain-specific models that simulate their unique physics, constraints, and environments. It’s analogous to moving from mass automotive manufacturing to custom assembly: people will be able to “build their own cars” because production will no longer be dictated solely by economies of scale. In healthcare, for example, smaller physics-informed models can simulate disease progression or treatment responses without relying on vast generalized systems. This eliminates hallucination risks and increases reliability in safety critical workflows.

Furthermore, the hyperscaler dynamic is also shifting here. Instead of running everything through massive centralized models, enterprises are distributing intelligence by blending foundational models with small language models, reducing hyperscaler dependence and optimizing performance for specific, local environments.

The shift is not just technical, it’s economic and operational.

The Key to Success: Knowing When to “Stop Thinking”

In enterprise environments, “thinking” has a real cost. More parameters rarely translate to better outcomes for most workloads. For many applications, GPT-5 class models are overpowered, expensive, and slow, leading to stalled rollouts and constrained use cases.

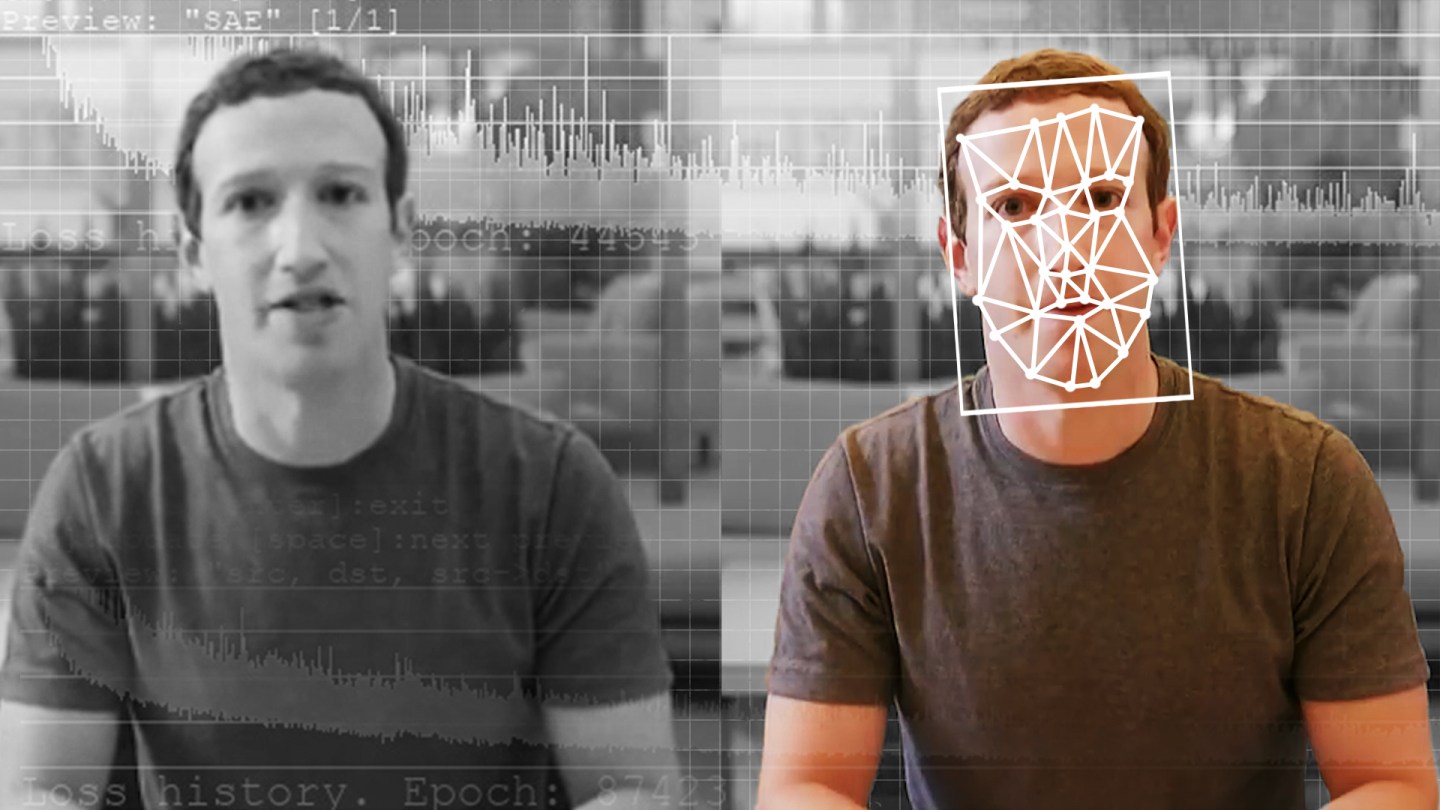

The foundation of AI 2.0 is constraint-aware intelligence. World models allow systems to build a task specific representation of reality, allowing systems to reason over what matters instead of recomputing understanding from scratch at every step. A similar discussion just sparked at Davos this year when AI pioneer Yann LeCun stated we’ll “never get to human-level intelligence by training LLMs or by training on text only. We need the real world.” His stance is that generating code is one thing, but reaching the cognitive complexity of, for example, level-five self-driving cars, is far beyond what today’s large models can do.

All of this ladders up to GPT-5 class models not being trained on real world scenarios. Whereas smaller, specialized, and efficiently tuned models can achieve sufficient accuracy faster, deliver dramatically lower latency, run at a fraction of the cost, and scale predictably with real world demand. In practice, AI shouldn’t think endlessly and it certainly cannot operate under a “one model to rule them all” architecture approach. It should operate within a defined decision space. The emerging pattern includes architectures that route tasks to the simplest effective model, escalate only when necessary, and continuously balance accuracy with speed and cost.

In other words, model size is the most dangerous metric on the dashboard. It’s a remnant of the 1.0 era that confuses capacity with capability. What truly matters is cost per solved problem: how efficiently a system can deliver an accurate, reliable outcome within the constraints of real operations.

Enterprises won’t win by running the largest models; they’ll win by running the most economical ones that solve problems at scale.

The Talent Arbitrage in AI 2.0

Talent is another critical variable of AI 2.0 that will dramatically shift AI industry dynamics, as success requires a workforce that can build models for highly variable applications. Today, only a small percentage of global talent can develop foundational models, and the majority of that talent is concentrated in a handful of global technology hubs.

Right now, researchers are the superstars and they’re compensated accordingly because they’re in high demand. But the shift to AI 2.0 demands a move from magicians to mechanics: professionals who can tune, maintain, and optimize models to solve specific real world problems. This talent transition will be one of the biggest arbitrage opportunities of this next phase of AI. If AI is to be truly democratized, enterprises need talent everywhere that understands sectors’ physics – whether in medicine, manufacturing, logistics, etc. – and can translate that expertise into specialized, usable AI systems.

So how does this impact 2026 AI roadmaps? It means we need to collectively work smarter, not harder. Budgets and strategies need to shift toward efficiency but also usability, favoring smaller, optimized models, hybrid and multi-model architectures, and systems engineered for durability at scale. Success metrics will evolve from model size to cost per outcome, time to decision, and tangible real world impact.

AI 2.0 isn’t about abandoning large models. It’s using them deliberately and economically. Organizations that adopt these practices will move faster, spend less, and achieve more than those still chasing brute-force scale.

The opinions expressed in Fortune.com commentary pieces are solely the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of Fortune.