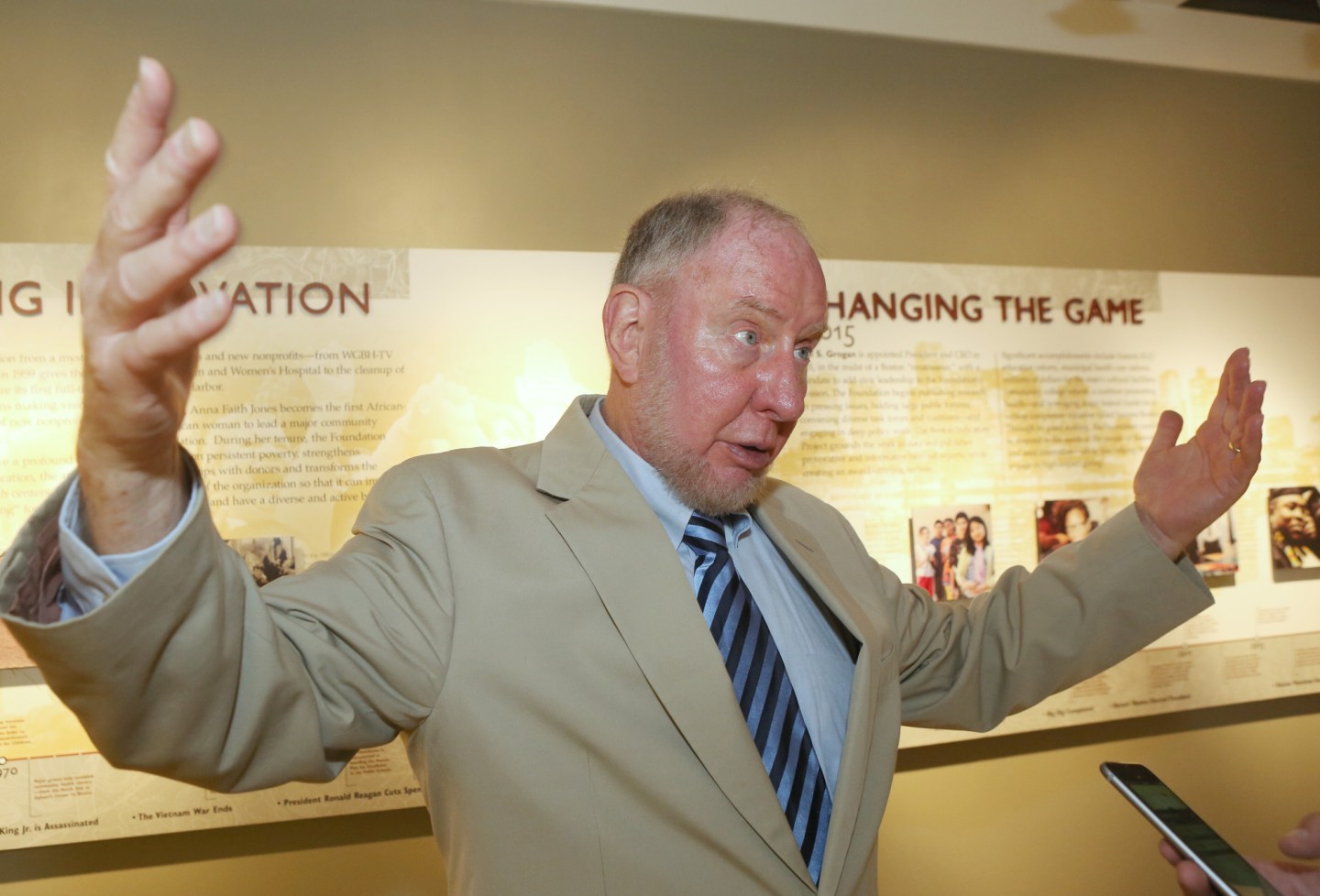

In an address on youth well-being, political scientist Robert Putnam, whose prescient 2000 book Bowling Alone predicted a quarter-century-long decline in American community, laid out a sweeping historical diagnosis worthy of his unofficial title: “the modern prophet of American loneliness.” Speaking at a recent Dartmouth-United Nations Development Programme symposium, the Harvard Kennedy School professor linked decades of social disintegration directly to the rise of populist authoritarian figures like Donald Trump—as well as to Gen Z’s struggles with anxiety and poor mental health.

Putnam asserted that the long-term decline in social connection and civic engagement—symbolized in his book by the fact that the number of people participating in bowling leagues has fallen off a cliff—is the core issue facing America. (Bowling leagues are down by “roughly 95% over the last now half century,” Putnam told symposium attendees.) This decline means Americans have become “disengaged from social connections,” which comes with profound consequences. Joining just one group can cut one’s chances of dying over the next year “in half,” Putnam argued, while the effects of prolonged isolation can impact the very stability of democracy itself.

Putnam argued in Bowling Alone about the importance of what he calls “social capital,” which is the value of social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them. He said he sees low social capital and social isolation as dynamics that fundamentally “bought us Trump.” He noted this connection was recognized by Steve Bannon, a member of Trump’s inner circle and a fan of Putnam’s work. Putnam pointed out that Bannon read Bowling Alone and concluded that people who are socially isolated are inherently “vulnerable to or open to authoritarian, populist appeals.”

Bannon talked to The New York Times‘ David Brooks in July 2024 about Bowling Alone capturing “the atomization of our society. There’s no civic bonding. There’s no national cohesion. There’s not even the Lions Club things that you used to have before.” Bannon argued the MAGA movement had given belonging back to people that was missing in their lives beforehand. “They have friends that they never had met before, and they’re in a common cause, and it’s changed their life. They’re on social media. Every day, they have action they have to do.”

Notably, Putnam said the “best individual-level predictor or aggregate-level predictor of Trump’s electoral support best by far is whether people are socially isolated or not.” Crucially, he stressed that Trump is merely a symptom, not the cause, of this crisis. The “real danger is that the problem which caused Trump is getting worse,” and until the underlying issue of social isolation is fixed, the country will “keep getting Trumps.”

Fortune recently spoke with the Chamber of Commerce’s Neil Bradley about his efforts with the College Board to introduce more business and personal finance courses into high-school education, when he pivoted to Bowling Alone. Bradley, the Chamber’s Chief Policy Officer, said he largely agreed with Putnam that prior generations had found personal fulfillment in various things such as going to church, belonging to a civic organization, or even bowling recreationally. When that stopped, “they try to put all of their personal validation in the place of business. They’re asking for their employer to be something beyond what their employer has traditionally been. I think that’s really hard.”

The cultural crisis of respect

The trend toward social isolation is exacerbating what Putnam characterized as a dangerous class gap in the U.S. While all Americans are experiencing greater isolation, his research suggests the decline is “especially true for middle class and working-class Americans,” particularly those without a college education.

Putnam insisted that this crisis extends beyond mere economic inequality, calling it a cultural problem rooted in a lack of “economy of respect.” He argued that “educated progressives are looking down our noses at the two-thirds of our fellow citizens who don’t have our privileges,” citing the example of Hillary Clinton’s infamous reference to Trump supporters as “deplorables.” Putnam added, “I actually worked for Hillary Clinton, personally worked for her her in her campaign,” adding “that made it so much worse … because she said out loud what they anyhow thought.”

Putnam has company in the form of legendary filmmaker Werner Herzog, who told Fortune in September that what he sees as “the heartland” of America is made up of “good people, but undereducated, underpaid, disadvantaged, not ever mentioned in the media, pushed to the margins.” Herzog said he is “outraged” when he hears talk of “flyover states” and warned in a similar vein to Putnam that these people are isolated at the country’s peril. “[They] are the majority, and you have to acknowledge it and do something about it.”

Where does loneliness come from?

Dartmouth economics professor David Blanchflower, whose work on the rise of “despair” among young workers was previously featured in Fortune, was instrumental in organizing the symposium and dove deep into historical attitudes about loneliness in a separate panel.

Blanchflower’s colleague from the history department, Darrin McMahon, argued that “loneliness is less of a universal human condition observable in all times and all places and more of a a recent historical phenomena.” McMahon said older literature shows that “solitude” was previously considered something of a virtue, and loneliness belongs to the modern, capitalistic age, calling it “an unanticipated consequence of development and a certain kind of progress.

McMahon also quoted the great 19th-century French writer Alexis de Tocqueville, known for his groundbreaking work of political science, “Democracy in America.” While traveling the U.S. in its infancy, according to McMahon, came a diagnosis of loneliness “as a consequence not only of increasing prosperity but of the pronounced individualism of democratic ages, which cuts each man as he puts it off from his contemporaries and threatens ultimately to imprison us in the loneliness of our own hearts.”

Agency and the moral imperative

Putnam presented a historical timeline—the “I-We-I century”—showing a dramatic swing in American life, moving from a period of high self-centeredness and inequality around 1900 to a peak of equality and social connection in the 1950s, followed by a steady decline back into isolation and polarization by the 21st century. The key lesson from the earlier upswing of 1900–1950s, he said, is that “we determine our own history we have agency.”

Putnam directly addressed Gen Z in how to navigate this crisis: “You didn’t cause the problem, we caused this problem. But it’s fallen to you to fix it and you have agency, you can fix it.” He urged young people to follow the example of reformers from the Progressive Era who reversed a similar decline. That reversal did not begin with economics, he argued; it started with “morality, the sense of who we are,” with the moral conviction that “we have obligations to other people” leading the way.

Furthermore, “mentoring matters.” Putnam raised the example of how, during the previous upswing, organizations like the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts were invented just a few years apart, because people recognized that young people needed mentors. Even team sports were invented for the “purpose of fixing the problem” of youth disengagement, he argued, citing basketball in particular. Putnam told Gen Z that new forms of social capital should be “fun” and not like “civic broccoli.” Noting that many serious social reformers have been under age 30 at their moment of maximum influence, Putnam reminded the audience that the “best revolutionaries are young people.”