The European Central Bank will start buying government bonds on Monday and has no intention of scaling back its plans to pump over €1 trillion into the Eurozone economy over the next 18 months, President Mario Draghi said.

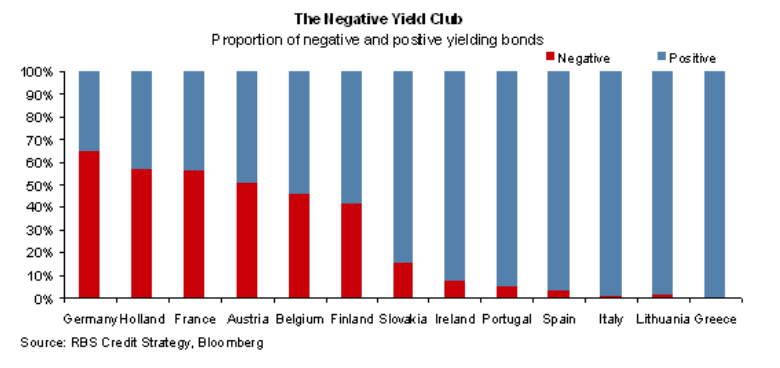

Draghi told his regular press conference that the bank will buy €60 billion ($66 billion) a month in government and bank bonds. He said he wouldn’t be put off by the fact that the yields on many government bonds in the Eurozone are already negative, saying the ECB would keep buying as long as yields were above the ECB’s deposit rate (which it left unchanged earlier at -0.20%, as expected).

That was music to the ears of the bond market, which has fretted in recent days that the ECB won’t be able to find enough bonds to buy. Buyers drove the yield on Italy’s 10-year benchmark down to a new record low of 1.34%. The German equivalent fell to 0.34%, while the euro hit a new 11-year low against the dollar of $1.1011.

In contrast to 2009, when the Federal Reserve started its ‘quantitative easing’ plan, government deficits are a relatively low 3% of GDP (Germany, the largest economy in the region, is even running a balanced budget), and banks are effectively forced by new regulations to hold large amounts of government bonds as buffers against sudden liquidity crises.

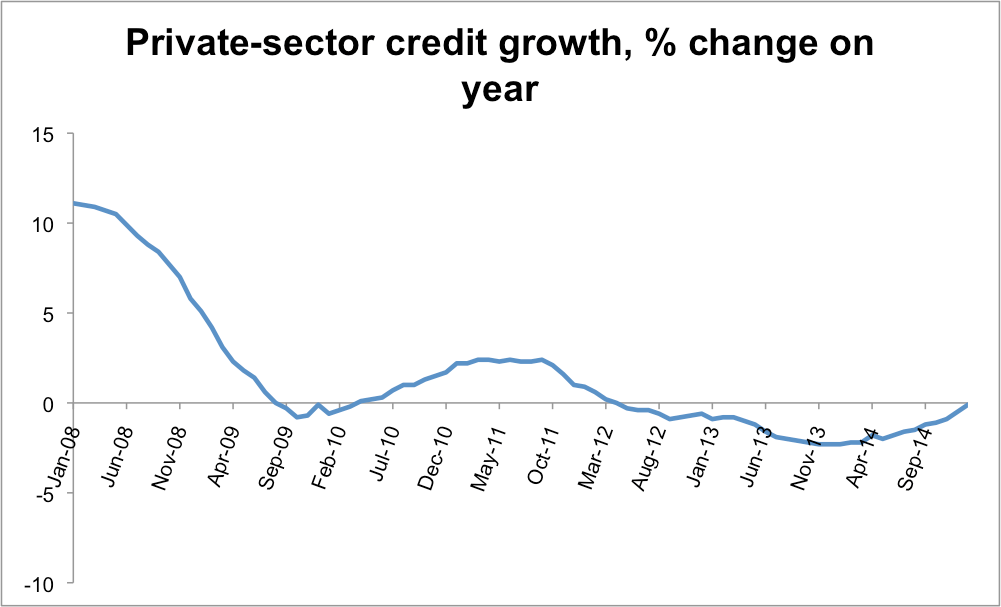

Things have been looking up more for the Eurozone in the last couple of weeks, as consumers have used the fall in oil prices to go out and spend more. Retail sales in January rose 3.7% on the year–the fastest rate in 10 years, according to Eurostat. At the same time, the ECB’s figures suggest that banks are making more loans to the real economy (and at lower rates).

The ECB revised up its GDP growth forecasts for 2015 and 2016 to 1.5% and 1.9%, from estimates of 1% and 1.5% three months ago. It also reckons that its new program of ‘quantitative easing’ will drive inflation back up to around 1.8% by the end of 2017.

But Draghi had little in the way of comfort for Greece’s new left-wing government, saying it will get no favors from the ECB until it successfully completes the existing bailout agreement with the Eurozone and International Monetary Fund. Athens is still dragging its heels over the reforms to things like VAT and pensions, but has bought itself until the end of April to present a new list of alternative reforms that it says will be more socially just.

Draghi rebutted criticism that the ECB should be more supportive, noting that it currently has exposure to Greece of €100 billion, or 68% of the country’s total gross domestic product.

“The last thing you can say is that the ECB is not supporting Greece,” Draghi said.

One of the Greek government’s biggest gripes against Frankfurt is the refusal to let it increase the amount of short-term borrowing via Treasury bills, to cover a widening gap in short-term financing. The bailout agreement limits this at €15 billion.

Repeatedly protesting that the ECB was “a rules-based institution,” Draghi said the bank isn’t allowed to finance government spending–an allusion to the fact that Greek banks are the only likely buyers for the bills and that they would immediately use them as collateral to borrow still more money from the ECB.

“That means Greece is under huge pressure now to secure the release of Eurozone funding very quickly in order to avoid having to default on payments,” said Christian Schulz, an economist with Berenberg Bank in London. “Greece’s negotiating position with its creditors has not strengthened today.”