China lowered its economic growth target for this year to 7% on Thursday. That’s half a percentage point lower than the past three years, and a far cry from the heady 2000s when gross domestic product grew by an average 10% a year.

Despite the obvious slowdown happening in the country, how you think about the target cut probably says more about you than it does about China.

There are two ways to interpret the news. For pessimists, the problems causing China’s economic slowdown don’t look like they’re going away anytime soon: the real estate market is falling deeper into distress; local government debt remains unsustainably high; and China’s model in the 2000s that supported double-digit GDP growth figures— in which Chinese firms produced steel and concrete and sold it to Chinese firms building skyscrapers, roads and tunnels—has run its course. In response to the slowdown, China’s central bank cut interest rates last weekend for the second time in three months.

For optimists, China may be slowing, but man is it still impressive! China is still the fastest-growing of the world’s 20 largest economies (or maybe the second-fastest after India, depending on whose statistics you trust more). And today’s 7% target growth rate translates into $1 trillion in additional activity during the year—a marginal increase that is more than half of India’s total GDP. The optimists also argue a lowered GDP target makes reforms easier to stomach: China’s pollution problems, caused by runaway development over thirty years, have been well documented, and solutions include scaling back the harmful industries. Lower targets should allow China to focus on sustained “quality” growth instead of cheap measures to boost GDP. Gavekal Dragonomics analyst Andrew Batson, who is no Pollyanna, offered the positive view on Thursday: “This is a good thing,” he wrote of the reduced growth target. “[I]t means less political pressure to build up debt and run polluting factories in pursuit of an unrealistic growth target.”

Do GDP targets even matter? In China, yes. Its economy is still immature in many ways. First, fiscal budgets in the country are based off the target number. Second, monetary policy is aligned with the targets too—the central bank can pump liquidity into the market if the economy isn’t reaching its “full” potential. Third, targets help reassure trading partners that China, unlike its European or U.S. competitors, will focus on predictably meeting economic targets that influence everything from natural resource prices to other emerging market economies.

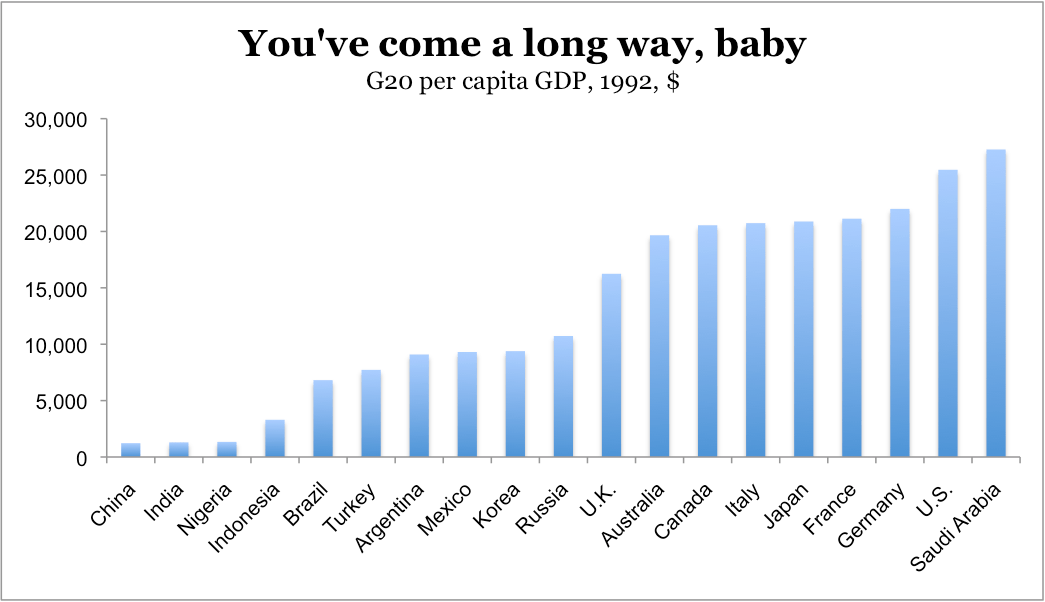

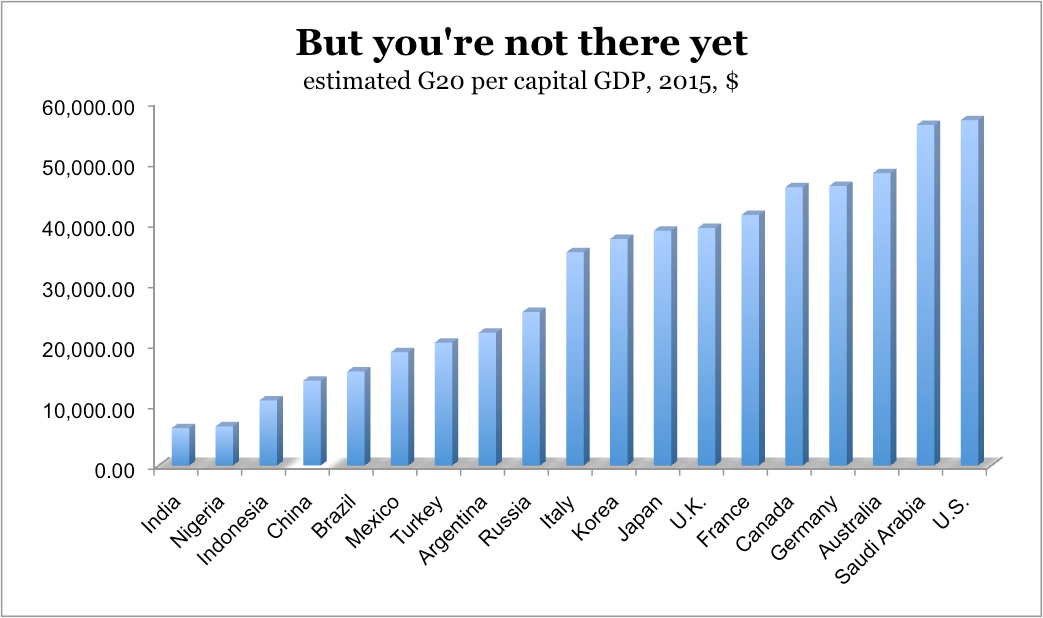

Do GDP growth targets matter to Chinese people? Less so. Whenever China’s GDP growth is in the headlines, it’s helpful to remember that individual prosperity isn’t driven by growth rates. China’s average per capita income remains very low despite the country’s standing as the world’s number two economy.

Even after standardizing prices in different markets, China’s gross national income per capita of $12,000 is half that of Chile’s and on a par with Peru’s.

Chinese author Yu Hua wrote several years ago about the issue from the perspective of the average Chinese citizen: “In 2010 China’s revenues are set to hit 8 trillion yuan, and we are told proudly that we are on the verge of becoming the second- richest country in the world, trailing only the United States. But behind these dazzling statistics is another, unsettling one: in terms of per capita income China is still languishing at a low rank, one hundredth in the world. These two economic indicators, which should be similar or in balance, are miles apart in China today.” Gavekal’s Batson points out that a developing country’s growth rate typically falls as incomes rise into developed market levels, which is happening now in China, but there’s a long way to go.

So how to view China’s slowdown and target reduction? Earlier this year, Rhodium Group analysts Daniel Rosen and Beibei Bao, who closely follow the country’s market, explained the causes of the country’s alarming slowdown. They pointed out that China’s growth is slowing because capital-intensive investment in heavy industry that creates few jobs, but outsized GDP, is slowing “while services, which use less capital and create more jobs, are growing.”

Their conclusion? “A headline value around 7% for GDP growth is consistent with employment requirements, provided reform continues to open room for new activity, especially in the services sector.”

In that way, a lower target growth rate doesn’t look so alarming. But it depends on your perspective.